Taking Root

In October of 2019, Abraham Granado and his father left their home in Valencia, Venezuela, to begin what would turn out to be a two-day journey to Colombia so that the teenage drummer could audition in Bogotá for Berklee.

The frontier between the two countries had been closed because of conflict, so the men took a 12-hour bus ride to a border checkpoint. From there, once in Colombia, they walked for a couple of hours to catch another bus that would take them on the 17-hour journey to the capital.

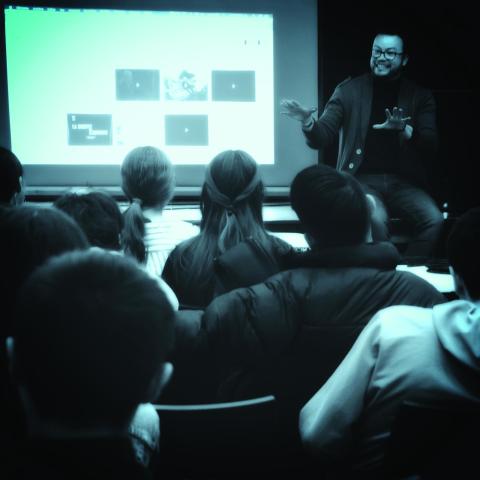

EMMAT student Abraham Granado

Image courtesy of Abraham Granado

The college was in town holding auditions at Escuela de Música, Medios, Arte, y Tecnologia (EMMAT), a Berklee academic partner and one of the premier schools of contemporary music in Latin America. Granado and his father made it to EMMAT, where Granado’s talent proved so impressive that he was not only admitted to Berklee but was also given a 50 percent scholarship.

Though this wasn’t enough for Granado to make the move to Boston, EMMAT offered him a scholarship to study there, and for the past two years he has been honing his skills to try out for a bigger Berklee scholarship while at the same time earning credits he hopes to transfer to the college.

As a Berklee academic partner, EMMAT is one of 24 music schools worldwide that have a credit-transfer agreement with Berklee. EMMAT students can transfer as many as 39 credits to Berklee, or nearly a third of what they will need to graduate. The arrangement allows students to save money by living closer to home while they take required courses such as ear training and harmony. EMMAT is among the schools that send the most students to Berklee: before the pandemic, it sent eight students, more than any other partner school except for SJA Music Institute in South Korea and Rimon School of Music in Israel.

Preparing students for Berklee is only one of EMMAT's many achievements. The school has also turned out leaders in the Colombian and Latin American music industries. Last year, former EMMAT students were nominated for 15 Latin Grammys, and one alumna, Juliana Velásquez, won the Latin Grammy for Best New Artist. Two others, Paula Arenas and Camilo, were nominated for Grammys.

Though EMMAT’s success is impressive, it has been hard-won, due in no small part to the dedication of its faculty and staff, and in particular to the grit and determination of its director, Alejandro Cajiao B.M. ’05.

Planting a Seed

Alejandro Cajiao B.M. '05

Image by Alejandro León

Cajiao’s road to EMMAT began with his time at Berklee. He had come to the college in 2000, after completing an economics degree at Boston University. At Berklee, he pursued his film scoring major nonstop for five years, all summers included, eventually racking up more than 200 credits. After graduating and spending an easygoing year in Los Angeles, he considered going to India to work in Bollywood, but a friend approached him with another idea: the friend’s cousin back in Bogotá, Maria José Morales B.M. ’01, wanted to open a music school, and the friend suggested they help her do so.

“I thought it was a wonderful idea. And a good project, good life,” Cajiao says. The friend, Alejandro Morales; Maria José Morales; and Cajiao banded together, and the trio later brought Pablo Schlesinger B.M. ’98 onto the team. With only $10,000 to start, they bought equipment and rented a 3,200-square-foot house in Bogotá’s upscale La Castellana neighborhood. “It was very scary because the rent was so expensive,” Cajiao says. The two Alejandros spent the next six months transforming the building into a one-of-a-kind school.

“I had to fight for what I was doing. And I believed in the school. I always believed in the school."

—

Claudia Valencia, the current academic director at EMMAT, was a student in those early years. “There was something charming and special about the house…they also had a spiral staircase leading to the second floor, and there was always a fresh pot of coffee in the kitchen,” she says. “It was so cozy. My experience as a student, when I first got there, was like, ‘Oh my god, this is the best place in the world. I’m at home here.’”

But for all of the new school’s charm, only 22 students enrolled the first semester, in 2007. This wasn’t enough to cover rent and salaries. The partners got jittery. Cajiao offered to buy their shares, with interest, and kept them in the fold: Maria Morales became a teacher, which she still is today; Schlesinger became academic dean and continued in that role until the pandemic; and Alejandro Morales stayed on for a year as an engineer.

Claudia Valencia

Image by Alejandro León

Cajiao, then, became the sole owner. “I had to fight for what I was doing. And I believed in the school. I always believed in the school,” he says. But he was worried, too; though the student population doubled the second semester, EMMAT still wasn’t on solid footing.

It was about this time, in 2008, that Alejandro Morales told him about an exciting new social media network. “He was telling me, ‘Man, get on Facebook. It’s so cool! You can check out your old school classmates and stuff.’” Cajiao wasn’t too interested, but Morales convinced him to join. “I got into Facebook, and then I see an ad that says, ‘We’ll bring chocolate bread to your office,’” Cajiao remembers. It was from a bakery in Bogotá. How, he wondered, did they put an ad on Facebook? He started asking around.

Advertising on Facebook wasn’t yet on many people’s radar. “I was probably one of the first companies in Colombia to put ads on Facebook,” Cajiao says. He put $5 a day on an ad, set up a webpage to link it to, and went on vacation to Cartagena, Colombia. When he came back, two weeks later, his email was full of people asking for information about the school. He upped the Facebook ad to $20 a day.

“I jumped from 40 or 50 students to almost 150,” he says. The following year, he bought the house next door to enlarge the school and accommodate its growing population. He also brought four more investors on board, who remain co-owners today.

A Fruitful Partnership

The next big leap forward for EMMAT came a few years later. Although Cajiao had been interested in being a Berklee partner since the founding of his school, his effort began picking up speed in 2012, when he asked Berklee to start doing auditions and interviews (A&I) there. At the time, he says, “I didn’t even have enough money to offer [Berklee] a welcome cocktail.” So he went to the U.S. Embassy, which not only agreed to host a reception but also offered to hold it in the ambassador’s home. After much coordination between the embassy and Cajiao, they put together an event for 250 of the most influential figures in the Colombian music and cultural scenes. Later that year, Berklee began annual A&I visits.

“It was so cozy. My experience as a student, when I first got there, was like, ‘Oh my god, this is the best place in the world. I’m at home here.’”

—

A few years later, in 2015, EMMAT became an official academic partner. Andrés Felipe León Suárez B.M. ’21 was among the first batch of students to take advantage of the agreement. León, a music production and engineering major who now works as a studio manager and producer in Bogotá's booming music industry, started taking classes at EMMAT while he was still in high school, as part of their junior program. He had been involved in musical theater since he was 8 years old and says that “within that medium, I guess I started hearing about Berklee engineers, Berklee teachers…and then I started coming to the seminars [Berklee] did every year at EMMAT and started getting into Berklee’s world.”

He remembers EMMAT as being very familial: “It’s very close…you could talk to Alejandro [Cajiao] and he would give you feedback after a concert. Or he would go to a class and just be there watching you take an exam.” This level of individual attention was matched by a first-rate music education, he says. “The teachers are excellent here. And they have professional backgrounds and work with top-class artists.”

Godi Gaviria B.M. ’18, another music and production engineering major who transferred EMMAT credits to Berklee, agrees. “The professors were all super top-level, and very experienced…so they could be very personalized—all the Berklee methodology and whatnot. And I felt, when I got to Berklee, like I was musically very mature, very prepared,” he says. Today Gaviria works in Bogotá. as a music producer and for the New York–based advertising agency Pickle Music Studios.

Both León and Gaviria say that EMMAT's partnership with Berklee was a principal reason they attended the school. In fact, Cajiao says, EMMAT's Berklee relationship is one of the most important ingredients of its success.

“Berklee is very attractive for students who come…they also have the option of going to local universities that have music programs, and they can graduate [from those] with a professional degree,” Valencia says. EMMAT offers two-year diplomas, not degrees. “But some people leave those universities and come here because they say…what I study in six semesters [in a university], you cover them here in two years. It’s very condensed and well-structured, and it’s Berklee material and Berklee methods.” And though a severely devalued Colombian peso has made transferring to Berklee much harder for many EMMAT students, they can still study with Berklee books and techniques.

“You know how they say human beings were created in the image of God?” Cajiao asks. “EMMAT was created in the image of Berklee.”

A Growth Spurt

When word got out that EMMAT had entered a partnership with Berklee, enrollment went up and both houses were packed. “So the only way was to move up,” Valencia says. EMMAT began work on a new home, in the Rio Negro neighborhood, and two years later moved into a six-story building that features nearly two dozen classrooms, a theater with seating for up to 170 people, a cafeteria, a spacious student lounge (and a rooftop lounge that affords a view of the city and the surrounding mountains), two ensemble spaces, two computer labs, several practice rooms, a resource center and shop, and two recording studios (one of which Cajiao is upgrading as part of a plan to get it Dolby Atmos–certified, a rarity for a music school in South America). Roger Brown, Berklee’s president at the time, attended the building’s 2017 inauguration.

Today, that building is full, to the point where the school is planning to limit the number of students it accepts. About 470 students attend EMMAT, which has about 25 staff members and 55 teachers, nearly a quarter of whom are Berklee alumni. (Cajiao estimates that about 40 Berklee alumni have taught at the school over the years.) EMMAT offers a weekend junior program for high schoolers, daytime classes mainly for those just out of high school, and nighttime classes that tend to attract 30- and 40-something professionals such as accountants and doctors. In addition to its contemporary music program, EMMAT offers film scoring and production programs, is designing a songwriting program, and is in the process of getting a government license for an entrepreneurship program. It also collaborates with Colsubsidio, a large employee-benefit company, on a jazz program in which EMMAT teachers provide instruction for 57 students.

EMMAT also boasts a robust online platform. Inspired, in part, by Berklee Online, EMMAT Online began in 2012, but it initially sputtered out. The next version was launched in 2015 but it struggled to thrive because, Cajiao says, he didn’t understand the online market: students wanted guitar and voice lessons, not harmony instruction videos. It wasn’t until 2020 that EMMAT Online took off, because of the pandemic.

A Tough Period

After Colombia went into lockdown in the spring of 2020, and the campus closed, EMMAT began holding classes over Zoom and Google Classroom. But the teachers felt uncomfortable and the students weren’t happy. Half of them dropped out. Soon, the money dried up and Cajiao couldn’t pay his employees. The teachers threatened a strike, putting the school on the verge of collapse.

Cajiao, who had moved with his wife and children to the mountains outside Bogotá, asked the teachers not to give up while he waited for banks to give him credit. “I sent a message almost crying,” he says. He also sent his faculty and staff large bags of groceries, thanks to a connection with a food-distribution center, to make sure they at least had something to eat.

Auspiciously, it was then that the Colombian government announced it would award 29 million pesos (about $10,000 at the time) for the digital development of music courses. EMMAT won the award and used the cash to pay teachers and create an entirely new online experience. Beginning in the summer of 2020, teachers started shooting videos of their lessons two weeks ahead of time so the content could be up on YouTube in time for class. Over the course of six months, they shot more than 1,000 videos.

“It was tough work for everybody,” Cajiao says. “All the teachers had to learn how to do videos, to edit…they had to become YouTubers, learn how to teach in a different way.” And, as at Berklee, while classes such as ensembles and piano labs proved difficult to transfer online, others were more adaptable. Percussion teachers, for example, made videos on how to build instruments at home. “Grab a bucket, grab this table, grab these seeds from the rice in this can…[the teacher] made it work,” Valencia says.

The online push saved the school, but it also permanently transformed how EMMAT educates its students post-pandemic. Cajiao and his team had learned about an educational concept from the 1990s called the “inverted classroom.” The idea is that students watch a lesson ahead of time and then spend class time going deeper into the concepts covered in the videos. “It’s not only for online students,” Valencia says.

Sunny Days Ahead

Cajiao sees expansion of EMMAT Online as the school’s “most important growth platform for the future,” because it’s a way to reach all of Latin America without laying a single brick. He’s looking into other ways to fortify EMMAT, too, especially as he eyes stepping down from his role as director in the next five to 10 years. He’s exploring a transfer-agreement program with a local university so that students who may not be able to go to Berklee have another option for finishing their degrees. He’d also be open to bringing in another investor, such as a university.

Cajiao says he intends to retain part ownership of EMMAT after he retires, but this will be from a distance. He plans to move to the countryside and farm. After more than 20 years of growing a school, he wants to grow food. “We never thought 15 years ago we were going to go this far with this school, and grow so much,” he says. His labors—and that of all those who’ve cultivated the talent at EMMAT—are bearing fruit: this April the school got news that four of its students were offered full scholarships to Berklee. One of them is Abraham Granado.

This article appeared in the spring/summer 2023 issue of Berklee Today.