Rap and Roots

“Barrio Maya and Múul Paax are trying to spread the message that, ‘Hey if we don’t do something, a huge part of our culture is going to be lost: our language,’” Guido Arcella M.M. '15 says.

Image by Evangeline Gala

Itzincab, a village of little more than four blocks nestled in Mexico’s Yucatán jungle, is named after an insect that has played a central role in the local Mayan culture for centuries. In the Maya language, itzincab means “little brother of the bee,” in honor of the honey-maker that has traditionally provided food and medicine to the Maya. But the indigenous stingless bee is in danger of vanishing, and so is the language that gave it its name.

Though many of Itzincab’s elders speak Maya, the younger generations mostly do not. The push to eradicate the language began with the Spanish conquistadors, but the threat to it today is from within Mayan communities, where it is sometimes viewed as a lower-status language relative to Spanish. Not only do Mayan children often not speak it at home, but those who use it in public are sometimes teased by their peers for doing so.

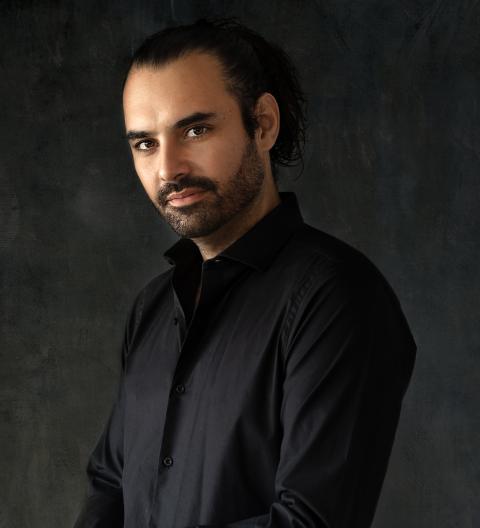

This stigma is one that Guido Arcella M.M. ’15 and his colleagues at Barrio Maya and Múul Paax are working to change. Arcella, who also runs a film scoring business and a recording studio, is the cofounder and managing director of both projects, which are trying to stem the loss of Maya and to support indigenous music. Barrio Maya is doing this by supporting both the continuation of Maya through rap and the musical aspirations of rappers on the peninsula, while Múul Paax creates and performs pre-Hispanic instruments.

“Barrio Maya and Múul Paax are trying to spread the message that, ‘Hey if we don’t do something, a huge part of our culture is going to be lost: our language,’” Arcella says.

Part of that “something” the groups are doing is using music to help the Mayan community restore pride in its culture and see its heritage as something worth preserving.

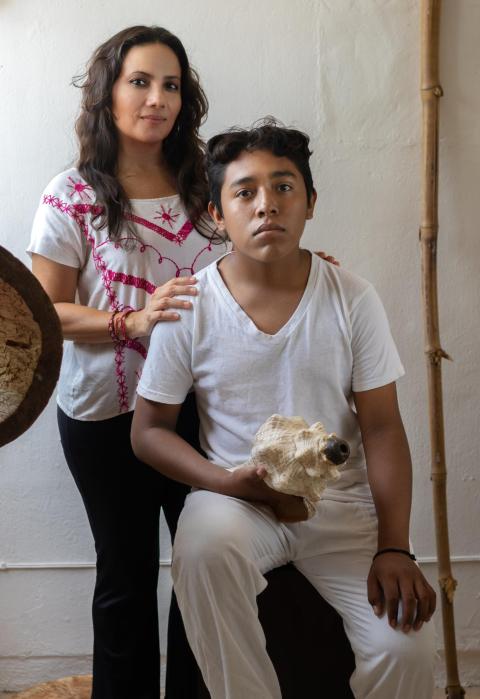

Nadia Zupo Herrera and José Nah Abnal

Image by Evangeline Gala

“You don’t appreciate what you don’t know,” says Nadia Zupo Herrera, the stagecrafting director for Múul Paax. “If you make it a daily practice to be exposed to Maya it becomes normalized and appreciated.”

The idea for the projects came to Arcella after he graduated from Berklee Valencia with a master’s degree in scoring for film, television, and video games. Arcella, a 32-year-old from Argentina, returned in 2015 to the Yucatán Peninsula, where he had lived for a time as a child in a Mayan village because of his father’s job in the area’s hospitality industry. Fresh out of the graduate program, he started a series of Mayan music labs at Hacienda Ochil, which was once a cattle ranch and henequen farm but now serves as a venue for private events and art projects.

Inspired by the success of these labs, Arcella wanted to figure out how to tap into the musical opportunities they presented. He reached out to Berklee Valencia’s International Career Center for ideas and was advised to contact fellow alumnus Gael Hedding B.M. ’05.

Hedding happened to be home, in Cancún, when Arcella got in touch with him in January 2017. “Having grown up in the region, I have an understanding of the challenges and opportunities that exist among Mayan communities,” says Hedding, who is now the director of the Berklee Abu Dhabi Center but remains an active advisor to Múul Paax and Barrio Maya.

The pair collaborated on a couple of events in which Hedding did live sound and production support. “Guido's enthusiasm and dedication was infectious,” says Hedding. Together, they began brainstorming the best way to leverage the Mayan community’s talent and potential. “We noticed that Mayan rap and pre-Hispanic instrument fabrication were both worth supporting, and that such support needed to happen through the form of education,” Hedding says, explaining how he and Arcella came up with the idea to start Barrio Maya and Múul Paax, which were, and continue to be, incubated by Fundación Haciendas del Mundo Maya (FHMM), a nonprofit Arcella’s mother directs that focuses on promoting cultural activities, nutrition, infrastructure, and economic and social enterprises in Mayan communities.

As Arcella and Hedding were considering where to take these projects, Arcella started two other endeavors that he still runs today: Arcella Sound, his film and video game scoring business, and Casona Indie Music Studio, his recording studio staffed with an engineer. It was at Berklee Valencia, he says, that he really learned how to run a studio, how to make his music sound professional, and how to use production tools to make that music shine.

Arcella manages to balance his leadership of these two projects with his own artistic work. This summer, Arcella was working on scores for two movies and two video games, in addition to numerous other engagements, including giving a master class in Mérida on soundtrack design in film; auditioning child musicians to be part of a group that would play at Festival Paax on the Mayan Riviera; and giving film and game composition workshops at the Musicians for the World event in Peru. Within the last year, he’s also done an artistic residency at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, where he had received his undergraduate degree in music composition and violin performance.

Music Among Us

One of the ways Arcella and Hedding launched their initiative, in 2018, was by offering weekend classes in Ochil, and later Temozón, to children aged 5 to 18 as part of a project they called Múul Paax, which means “music among us” in Maya. Divided into three groups by age, the kids would rotate among instructors who would teach them stagecraft and choreography, instrument construction, and music theory. Some children would also learn how to play instruments. During the week, the 50 or so participants would disperse back to their communities and rehearse in their villages’ cultural centers.

But, as with nearly every other group activity in the world, these classes ended in the spring of 2020. As the pandemic progressed, Arcella and his team looked for new ways to keep the children involved. For the youngest students, Múul Paax provided education through Zoom video calls, which culminated in recorded video projects in each of the participants' communities. In these videos, the students dressed in costume to personify the animals and food found in a Mayan milpa, or cornfield and garden.

One girl who participated in the program, Sinahi, said it made her happy because she got to meet children from neighboring towns and learned many new things, such as how to play the flute. As is common for children in the area, Sinahi, now 11 years old, had never had any music education.

To complement the Zoom instruction, Arcella’s studio made a series of audiobooks explaining Mayan cosmology through a child’s eyes. The series, called Llamada del Caracol (“Call of the Shell”), aired on national radio.

Meanwhile, the oldest group of Múul Paax students, who lived mostly in the Campeche town of Bolonchén de Rejón, gathered in the local park to pick up the on-and-off Wi-Fi signal on their cell phones and connect to lessons over WhatsApp. It was this group that acquired its own space, also in Bolonchén, where they could get together twice a week to work on building their instruments and practice playing them, which they continue to do today.

The musicians of Múul Paax

Image by Evangeline Gala

‘We Are Them’

During one of these semiweekly sessions, in mid-June, 17-year-old Angel Nah Abnal stood behind a table that held an array of whistles, flutes, rattles, and conches, and went through the function and purpose of each one.

He first picked up a vase-shaped vessel no larger than his hand, cupped it, and blew into the neck. As he slowly removed his palm, the instrument released a whooshing sound that mimics the roar of a jaguar, an animal native to these parts. Another pocket-sized object, which had an inscrutable little face carved on it, is called a silvato de la muerte (“whistle of death”); it produced a shriller sound. This is the instrument the Maya would play to scare off their enemies during battle, Nah Abnal explained.

Angel Nah Abnal

In a way, Nah Abnal is also using the whistle of death to defend his people. “I think it’s important to raise this Mayan culture because the new generations are ashamed to belong to the Mayan culture, and that is a big mistake because we should feel proud of our culture and what we are,” he says in a video about Rap & Raíz (“Rap and Roots”), a collaboration between Múul Paax and Barrio Maya in which the two groups offer joint concerts.

Nah Abnal’s sentiment is widely shared in Múul Paax. His bandmate and brother, José Nah Abnal, says that Múul Paax aims to rescue Mayan music through the instruments. “Because we come from the Maya, more than anything, we need to respect this type of music,” he says. “It’s our origin.” José Nah Abnal plays turtle shell as well as tunkul, a carved-wood percussion instrument that produces two tones, one to symbolize the day and the other the night. It represents, he says, the duality of nature.

Standing next to the brothers was 18-year-old Angel Poot Tec, who plays the zacatán, a drum made out of a tree trunk and deer skin. He says he too is concerned about people abandoning the culture.

It’s this feeling of loss of culture that inspired the group’s leader, Roman Dzul, a local music instructor, to put together the group Yum Paax (“God of Music”) seven years ago to teach children Mayan ritual music. Several members from this group, along with Dzul, joined what is now Múul Paax. For him, it’s important to pass this musical tradition to the young to keep it alive.

Pedro Salvador Hernández

Image by Evangeline Gala

One way to ensure this legacy, says Pedro Salvador Hernández, the group’s instrument construction consultant, is to give Mayan performers the ability and know-how to build their own tunkuls, zacatáns, ocarinas, rainsticks, and the like.

Though they can’t be sure that the instruments they build are exactly what their forebears used, they know from ancient paintings and evidence from archaeological digs the type of instruments the Maya of pre-Hispanic Mexico likely played.

However, it would be a mistake to speak of this civilization as one that existed only in the past. “They say the Maya are not around anymore, but that’s a mistake, they still exist; we are them,” Dzul, the teacher, says.

This year, Múul Paax has had four big concerts around the Yucatán Peninsula, and has performed at various Mayan ceremonies, such as those to bring rain. These concerts include the group’s Rap & Raíz collaborations with Barrio Maya, which provides a logistical and educational platform for the development of Yucatán rappers who incorporate Maya into their rhymes.

Indigenous Guys

One rapper who’s benefited from Barrio Maya’s programming is a 21-year-old from Espita, Yucatán, who calls himself LA2C. He began rapping at age 11 and soon had ambitions to record. But living in a small town that’s a two-hour drive from either Mérida or Cancún, he had little access to studios. That is, until a local gang offered him the opportunity to use the recording facilities belonging to one of its members.

“I was part of the gang but not because I wanted to be but because they were giving me the possibility to record,” LA2C said.

As a reluctant member of the gang, LA2C says he found himself in many conflicts. These culminated in an incident that changed his life. At 14, he was part of a fight that left him badly beaten and unconscious. When he came to, he realized that he had been deposited a block from his home, saved by an adult he didn’t know and hadn’t seen in town before. It felt, he says, like divine intervention. He considered it a second chance and realized that day that he wanted to dedicate his life to doing good. He left the gang and renewed his focus on his music.

From left: LA2C, Verso Maya, Masewal

Image by Fernando Santandreu

Today, he works with a Mayan rapper and producer who goes by the name Masewal, which is Maya for “indigenous guy,” and LA2C’s lyrics, a mix of Spanish and Maya, are about spreading positivity. On a day this June in Masewal’s studio, moments after LA2C describes his story, he performs his song “Bienvenidos a Yucatán.”

He starts, in Spanish:

Welcome to my state, welcome to my land

You are all invited. If you come here, you stay

Because you will truly fall in love with its festivities, traditions, its stories

And embroidery of my mestizo people

Of the Maya people, my culture is first

About halfway through the tune, he switches to Maya and tells a story about a day in the life of an indigenous man who gets up, goes to the milpa, cuts some wood, and spend time with his family.

As he’s rapping this, he’s steps away from the milpa belonging to Masewal’s family. Though loosely translated in English as “cornfield,” a milpa is a system that traditionally provides the Maya with all their needs for a comfortable life, including corn and other crops, medicinal honey, and material to build houses, says José Arellano, FHMM’s biodiversity senior advisor.

These days, some young Mayan men are also seeking different ways to find a comfortable life. LA2C, like many others in the peninsula’s interior, makes his living by working in construction in the booming Mayan Riviera, where luxury resorts have sprung up from Cancún to Playa del Carmen to Tulum. This influence is also showing up in LA2C’s rhymes. In “Bienvenidos a Yucatán,” he raps:

We are truly fortunate to have what we have

That we earned with effort

My culture is universal

It is always recognized all over the world

Everyday they visit it and admire it

Its gastronomy, cenotes, and its beautiful beaches

LA2C’s rhymes flow easily over the tune’s catchy beat. “Barrio Maya helped me to professionalize the music of my songs,” he says in the Rap & Raíz video. “They trained me in approximately 10 weeks, starting with music theory; they taught me to compose, to make the basis of a track. And then I learned to structure a lyric with coherence.”

Barrio Maya delivered this instruction via video. The prerecorded lessons, offered annually through a free 10-week series called Make Rap Music from Your Cell Phone, cover music technology that helps rappers make their own beats in a software app; lyric writing, including in Maya; and stagecraft and choreography. They also contain general master classes by another rapper.

LA2C started rapping in Maya about five years ago, shortly after he met Masewal, who himself had started rapping in Spanish before switching to Maya. The two rappers speak Maya at home, but Masewal says he noticed that people are forgetting how to speak it. As say the members of Múul Paax, Masewal says it’s important for him to rescue this part of his identity and to let people know about his culture and music.

Another rapper at Masewal’s studio that day in June, a 26-year-old who goes by the name Verso Maya, emphasized that there is no contradiction between embracing rap—and the style that often goes along with it—and being Mayan. Even though they might dress differently from what some might expect of people from his culture, they are still Mayan, he said.

Fernando Santandreu

Image by Evangeline Gala

“Rap, Barrio Maya, Múul Paax, and other projects are looking for the people to be proud of their culture, and their music, and their food,” says Fernando Santandreu, the groups’ education coordinator.

Though both groups are currently incubated by the nonprofit FHMM, they help support themselves through concerts, such as Rap & Raíz, instrument sales, and some fundraising. In addition, Arcella ran an online film scoring competition called Rec Change from 2019 to 2021 to help raise funds for Barrio Maya. Still, Arcella says, a major goal of his is to make the groups self-sustainable by gaining the long-term financial support of more organizations.

Come, Little Iguana

Barrio Maya and Múul Paax continue to collaborate in ways beyond the Rap & Raíz concerts. One might think that acoustic pre-Hispanic-inspired music might not mesh well with rap but, says Santandreu, the combination is actually a new and surprising way to make music.

Back in Itzincab, the town named after the bee, children gather in the village's cultural center to describe their experience with Pat Boy, a well-known Mayan rapper who worked with them a year before their workshops with Múul Paax.

Pat Boy, who is from the neighboring state of Quintana Roo, had received a federal grant in 2019 to hold a cultural workshop and contacted Arcella for ideas on what to do. What resulted was a workshop in Itzincab for children aged 8 to 14 in which the rapper worked with the kids over the course of three months, teaching them to put together a rhyme in Maya, build a song, and record the final product.

The children, now in their early teens, said it was a lot of work: They had to study Maya, learn a bit about various rap genres, practice how to move during a performance, and familiarize themselves with the basics of recording and production, such as how to use a microphone.

It was an opportunity, Pat Boy said in a video about the workshop, for the children to learn that Mayan rap exists and to see what can be done in the Maya language. “Many people apparently do not speak Maya. But with this workshop many have already become interested in learning phrases, saying things in Maya,” he said.

The children describe the process of making the video as a happy and emotional one. Everyone in town was very proud when the song, in which a little iguana is invited to town to enjoy some food, was posted on YouTube. In school, teachers played the recording for the children to enjoy and dance to.

And despite some bullying from kids in a neighboring town who derided the novice rappers for using Maya, the children smile when they describe their time with Pat Boy and remember the song and video.

"Everyone has a goal. Maybe it's to become a writer, a poet, a teacher—whatever it might be," Pat Boy said. “But now they see the great importance of what the Mayan language is, [and] what can be done as an artist.”

Residents of Itzincab meet with Guido Arcella and colleagues.

Image by Fernando Santandreu

This article appeared in the fall/winter 2022 issue of Berklee Today.