Berklee: A Sonic Timeline

Berklee’s Latin motto, Esse quam videri, can be translated as “to be, rather than to seem.” This call to be true to one’s self and one’s art has not wavered since Larry Berk founded the school in 1945. The idea was simple, yet revolutionary: study not just the music that’s been made, study the music that is being made—study the history of music, but also make music history.

To take stock of where we’ve been, we couldn’t think of a more fitting tribute to the school, from its genesis as Schillinger House to present-day Berklee College of Music, than to create a playlist featuring one song from each year of the school’s existence. The songs here showcase not just an impressive list of notable alumni (though it is that) and a collection of accolades (it is that, too)—nor are they meant to be an exhaustive record of Berklee’s contributions to music over the past seven and a half decades—but rather, they are the stories of those who have shaped and been shaped by the Berklee universe. Many of the featured artists are alumni or have been faculty members, or were presented with honorary doctorates.

Listening to these songs, you will hear something like an audio version of a time-lapse camera, hearing big band shift to bebop and fusion, sitcom themes to iconic film scores, the music of the African diaspora to the traditional music of India, Spain, Mexico, China, and many other places.

Taken together, the list shows that where we’ve been can indicate where we’re going, and ultimately, how studying contemporary music becomes music history.

The 1940s

Click the image to learn more and listen to the song.

1945Charlie Parker, “Ko Ko”

1945

Charlie Parker, "Ko Ko"

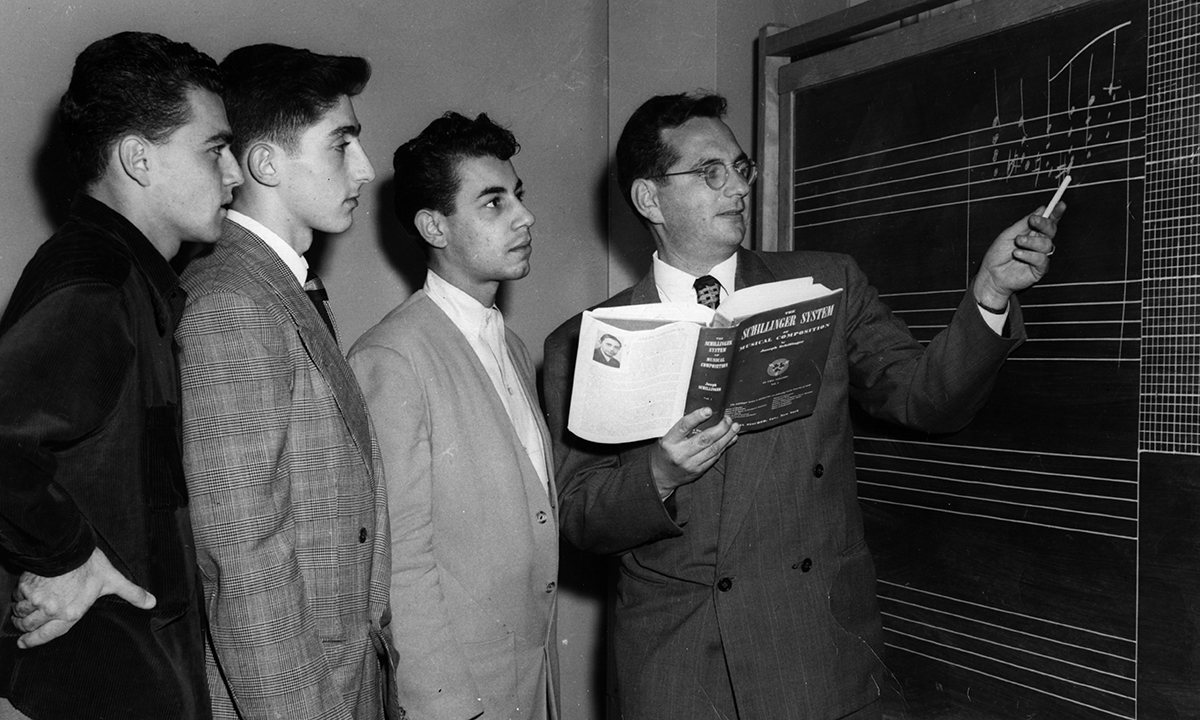

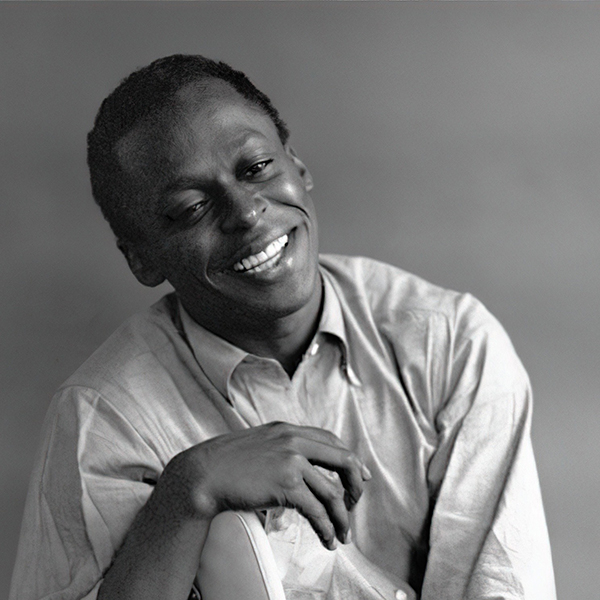

In 1945, Lawrence Berk purchased a three-story building at 284 Newbury Street and opened it as a new music school. An MIT-trained engineer who had left a stable job at Raytheon to pursue teaching music full-time, Berk never expected to start a school at all. “Talented kids seemed to find me and I got busier and my best students became teachers and that’s how the school started,” he told the Boston Globe in 1993. Berk named it Schillinger House, as a tribute to his musical mentor, Russian music theorist Joseph Schillinger. (Nine years later, he’d rename the school Berklee, after his son, Lee Eliot Berk.) It was the first institution of higher education in the U.S. to be founded on the study of jazz, the popular music of the era. In November of that year, saxophonist Charlie Parker recorded “Ko Ko,” one of his early masterpieces, with Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Curly Russell, and Max Roach. The session, Parker’s first as a leader, is considered by many to be the first time that bebop—a new form of jazz characterized by rapid tempos, improvisation, and instrumental virtuosity—was ever recorded. The bebop movement had a profound impact on Berk as he built a music curriculum that would become known around the world for its focus on contemporary trends and styles.—Nick Balkin

1946 George Gershwin, “I Got Rhythm”

1946

George Gershwin, “I Got Rhythm”

Beyond its emphasis on jazz and popular music, Lawrence Berk’s curriculum, per a school catalog from 1946, was tailored to serve a broad range of careers, “from the writer of popular songs to the symphonist, from the arranger of tunes for dance band to the orchestrator of television and moving picture scores, from the composer of radio jingles to the creator of tone poems.” Berk's notebooks from this era reveal Schillinger’s influence on the school’s early academic development. A cult figure among music theorists, Schillinger devised an unorthodox compositional approach that used mathematics to generate melody, harmony, and rhythm, as well as graphs, rather than traditional notation, to organize musical elements. The Schillinger System, as it was known, attracted such notable students as Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, Tommy Dorsey, Oscar Levant, and George Gershwin, whose jazz standard “I Got Rhythm” is featured below. “Anyone who meant anything studied with him,” said Berk. Inspired by Schillinger, Berk pioneered a new approach to music education by creating an organizational system for the elements of jazz and other modern music styles. In doing so, he created a model on how to prepare students for careers in contemporary music(Opens in a new window). —Nick Balkin

1947 Louis Armstrong, “Mahogany Hall Stomp”

1947

Louis Armstrong, “Mahogany Hall Stomp”

Boston provided fertile ground for the postwar jazz scene to take root, and it bloomed in 1947: Louis Armstrong, arguably the most influential jazz musician of the 20th century, played a triumphant concert at Symphony Hall, and Wally’s Cafe Jazz Club, the first Black-owned jazz club in New England, opened its doors (inspiring the Hi-Hat, a whites-only club, to integrate). “The stretch of Mass. Ave. between Huntington and Columbus was, by the late ’40s, Boston’s answer to 52nd Street in Manhattan—with not only the Roseland, but the Savoy Café, the Hi-Hat, Wally’s, and a handful of smaller clubs,” Boston Magazine wrote in a 2006 article. Wally’s has since been a boon to the development of local artists, hosting figures such as Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, and providing a venue for the city’s up-and-coming musicians—including Esperanza Spalding BM ’05 and Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah BM ’04. At the same time, the school that would later become Berklee began to conduct classes on a full-time basis, and was authorized to accept students on the G.I. Bill, many of whom were eager to dive into the jazz scene both inside and outside the classroom. —Kim Ashton

1948 Woody Herman, “Four Brothers”

1948

Woody Herman, “Four Brothers”

Despite the emergence of bebop—jazz intended primarily for listening—the public hadn’t lost its appetite for danceable tunes. In 1948, Schillinger House created two dance orchestras, giving students the chance to hone their skills off campus at venues throughout the Boston area. One ensemble was led by Joe Viola, who would go on to become the founding chair of the Woodwind Department and teach or mentor many notable students, from Quincy Jones ’51 and Herb Pomeroy ’52 to Joe Lovano ’72 and Donald Harrison ’81, over the course of his 49-year Berklee career. The other was led by Freddie Guerra, a former member of Glenn Miller’s Army Air Force Band in Europe during World War II. A particularly influential figure for Schillinger House students in the late ’40s (according to a poll from the first issue of The Score, the school’s student newspaper) was Woody Herman. One of the first big-band leaders to incorporate the language of bebop into his music, Herman would become a frequent visitor to Berklee over the years. At the college’s 1977 commencement, Berklee presented a wheelchair-bound Herman with an honorary doctorate. Injured in a car accident shortly before the ceremony, Herman told Lawrence Berk that he’d attend commencement “if I have to be carried in on a stretcher.” —Nick Balkin

1949Miles Davis, “Boplicity”

1949

Miles Davis, “Boplicity”

As the 1940s wound to a close, Berk didn’t need to look too hard for evidence that his vision for teaching music through a contemporary lens was coming into sharper focus. Admission counts for Schillinger House now numbered over 500 students, and the school was featured regularly in the pages of DownBeat and Metronome. While these early years tend to be described as mostly jazz-focused, new majors were added this year in music education(Opens in a new window), arranging, composition(Opens in a new window), and applied music. Combined with the earlier additions of training for dance orchestras and TV/radio jingle composition, you have a school well-positioned not to follow an industry, but to exist and grow alongside it. And one of the most significant evolutions in 1949 was Miles Davis’s version of Cleo Henry’s “Boplicity,” (eventually appearing on 1957’s seminal Birth of the Cool). Despite the song title’s nod to bebop, “Boplicity'' was warmer and less aggressive than bebop. With its focus on tonal color and subdued rhythms, it helped set in motion the emergence of cool jazz, a form that would be perfected in the decade to come by Davis and greats such as Gil Evans, Charles Mingus, Dave Brubeck, Stan Getz, and future Berklee faculty member John LaPorta. —Bryan Parys

The 1950s

1950Various Student Artists,“Boston Jig-Saw: A City Set to Music”

1950

Various Student Artists, “Boston Jig-Saw: A City Set to Music”

What is the sound of a city? By the beginning of the ’50s, the economic and cultural boom that occurred after World War II was resounding around the country. On a local level, part of the bustle was at Schillinger House, which was coming into its own as a fixture of Boston culture. Larry Berk began this year what would become an annual spring concert tradition. Titled A Montage of Modern Music, the series highlighted student performers, composers, and arrangers, much like the Singers Showcase and Words and Music Festival events of today. To pay homage to the school’s urban environs, the inaugural concert, called Boston Jig-Saw, sought to evoke the city’s pulse with pieces inspired by five local landmarks: the Public Gardens, the corner of Tremont and Boylston streets, Fenway Park, the Fish Pier, Harvard Yard, and Filene’s Basement (okay, let’s just say that most of this list has endured as a landmark…). Much like other past and contemporary works inspired by their surroundings, such as George Gershwin’s An American in Paris (1928) and Steve Reich’s NYC-ode City Life (1995), Boston Jig-Saw was composed from a place of deep listening. “That's what music is, the listening,” said Boston Daily Record (now the Boston Herald) journalist George W. Clarke in the Jig-Saw program. “[A]nd then the telling of what you heard down in that little secret pocket of your mind…which made you want to be a musician in the first place.” —Bryan Parys

1951Charlie Mariano, “Boston Uncommon”

1951

Charlie Mariano, “Boston Uncommon”

When you listen to saxophonist Charlie Mariano’s “Boston Uncommon,” it’s not immediately clear what’s uncommon about his artistry. It’s easy to hear Mariano’s roots in big band and swing, as well as his growing interest with the bebop stylings of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. From there, the breadth of his music continues to grow, making what is uncommon about Mariano something we can only fully appreciate with the benefit of hindsight. A few years after this song was released, he’d return to Berklee as a faculty member, briefly marry Toshiko Akiyoshi ‘59—who, as a woman and prominent jazz bandleader in the ’50s, was already charting an uncommon path—and then, in 1971, he’d leave Berklee and America for Europe. There, he’d collaborate with experimental double bassist Eberhard Weber and blend elements of Asian classical music into jazz, particularly through his use of the nadaswaram, a double reed instrument with origins in Tamil Nadu, India. What was uncommon about Mariano, then, is what’s becoming more common at Berklee: a global curiosity and a bold desire to connect music across cultures and borders. —Bryan Parys

1952Les Paul and Mary Ford, “My Baby's Comin' Home” (Bill Leavitt)

1952

Les Paul and Mary Ford, “My Baby's Comin' Home” (Bill Leavitt)

Bill Leavitt, one of the school’s earliest alumni, was also among the first to cowrite a popular hit, 1952’s “My Baby’s Comin’ Home,” performed by Les Paul and Mary Ford. When he entered Schillinger House in 1948, Leavitt was only the third guitarist to have studied at the school. It was the first step in a career that would deeply influence guitar studies at Berklee. He replaced Jack Petersen as chair of the Guitar Department(Opens in a new window) in 1965 and stayed on until his death in 1990. Over the course of his time at the college, Leavitt wrote 10 instruction books, including the classic three-volume work A Modern Method for Guitar, which is still used today. “He wrote the bible for guitarists, the guide for learning to play it in real musical terms,” said Ronald Bentley, former associate dean of faculty. Among Leavitt’s students were many guitarists who would go on to become standard-bearers, including John Abercrombie ’67, Bill Frisell ’78, John Scofield ’73, Mike Stern ’75, and Steve Vai ’79. At the same time, he kept a foot in the composing world, writing 355 arrangements for guitar ensembles. —Kim Ashton

1953Teddi King, “Round Midnight”

1953

Teddi King, “Round Midnight”

Long before American Idol and The Voice, there was Community Auditions, Schillinger House’s very own amateur talent competition. Produced in partnership with WBZ-TV, it was one of New England’s highest-rated shows for years, airing from 1950 to 1986 (though Berklee’s involvement ended in the late ’60s). Buoyed by the show’s popularity, in 1952 Berk created a second talent competition, Tune Tryouts, in which amateur composers submitted original music to Schillinger faculty, who then chose the top three songs to be performed on the show. Viewers voted for their favorite song to the tune of 6,000 postcard ballots each week. The show’s breakout star, however, was not a songwriter but the singer of the house band, Schillinger House student Teddi King, who went on to become a national presence in jazz and pop. “She was barely five feet tall, but her voice was large and relaxed,” said Whitney Balliett, a critic for The New Yorker. “She never hurried a note, even at fast tempos, and she gave each song a serenity that carried it through the noisiest room.” —Nick Balkin

1954Charles Mingus and John LaPorta, “Four Hands”

1954

Charles Mingus and John LaPorta, “Four Hands”

In 1954, reeds player/composer John LaPorta recorded the song “Four Hands” with jazz bassist/composer Charles Mingus for their coreleased album Jazzical Moods. The record was a project of the Jazz Composers’ Workshop, which LaPorta cofounded with Mingus and others as an experiment in combining classical music with jazz. LaPorta was trained classically but launched his career at the height of the big band era. In New York, he was soon playing with stalwarts of both musical worlds: Woody Herman, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Buddy Rich, and Lester Young, alongside performances with the Boston Pops, Leonard Bernstein, Igor Stravinsky, and others. LaPorta joined the Berklee faculty in 1962, later founding the Instrumental Performance Department. “Within three years, he was something of an icon,” said Larry Monroe, former vice president of Academic Affairs. “John could get music out of three stones and a corn cob.” LaPorta said, “I think as a teacher I should be concerned about hidden talents, not obvious ones. We’re supposed to help people grow and become whatever they can be.” —Susan Gedutis Lindsay

1955Herb Pomeroy, “Moten Swing”

1955

Herb Pomeroy, “Moten Swing”

Though he’d played trumpet around his hometown of Gloucester, Massachusetts, as a teenager, Herb Pomeroy didn’t necessarily intend for this to turn into a career. After high school, he enrolled in Harvard University to become a dentist. But after a year there, he left, and went to Schillinger House to study until 1952, when he became a full-time trumpet player. Over the next few years, he performed with Charlie Parker, Stan Kenton, and Lionel Hampton, and appeared regularly at the Stable, a Huntington Avenue jazz club known as an incubator for local talent. In March 1955, his resident quintet, the Jazz Workshop Quintet (later also called Herb Pomeroy and His Stablemates), recorded Jazz in a Stable, an album that Nat Hentoff (who was well on his own way to becoming famous in the jazz world, as a critic and writer) gave five stars to in DownBeat magazine. One of the record’s tracks was “Moten Swing,” written by Bennie and Buster Moten. A year after the album came out, Pomeroy went back to Schillinger House, this time as a teacher, and began what would be a nearly 40-year career as one of Berklee’s premier jazz educators. Stablemates Ray Santisi and John Neves would later join him on the faculty. —Kim Ashton

1956Toshiko Akiyoshi, “Between Me and Myself”

1956

Toshiko Akiyoshi, “Between Me and Myself”

In the early 1950s, pianist and bandleader Toshiko Akiyoshi ’59 was making a name for herself in the male-dominated world of jazz and had released her debut album, Toshiko’s Piano, the result of a session arranged by Oscar Peterson, when she heard about Berklee from a fellow musician. Akiyoshi wasted no time in writing to founder Lawrence Berk, asking for the opportunity to study at the school. Berk was already familiar with Akiyoshi’s work and in 1955 awarded her a full scholarship to Berklee. She became the school’s first Japanese student when she arrived in Boston in 1956, the same year she released her second album, The Toshiko Trio (aka George Wein Presents Toshiko). The album showcases Akiyoshi’s considerable talent as a composer, notably on the stunning opener “Between Me and Myself.” One of many talented students to come to Berklee from around the world at that time, she was at the forefront of helping the school transform into an international hub for jazz education. Through a trailblazing career that has spanned seven decades, 14 Grammy Award nominations, and countless other accolades, Akiyoshi’s influence on Berklee and jazz is still being felt today. —Margot Edwards

1957Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington, “Satin Doll”

1957

Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington, “Satin Doll”

The year that Duke Ellington was inducted into the DownBeat Hall of Fame, he stopped by Berklee to sit in with students as they rehearsed their annual concert, which featured their arrangements of his music, in recognition of the DownBeat honor. The tribute prefigured what would become Herb Pomeroy’s course Arranging in the Style of Duke Ellington and focused on the jazz legend’s “philosophical approach to the band” in which all members were allowed to explore their styles and express themselves fully. That same year, 1957, Ellington and his orchestra released the album Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Duke Ellington Song Book, with Fitzgerald. The record included the tune “Satin Doll,” which Ellington would return to Berklee to perform in 1971, when the school awarded him an honorary doctorate of music, the first that Berklee had ever bestowed. Lawrence Berk introduced Ellington by saying that “there is no aspect of modern American music and jazz that has not felt the impact of his unique talent.” —Kim Ashton

1958James Progris, “I Would if I Could” (Jazz in the Classroom)

1958

James Progris, “I Would if I Could” (Jazz in the Classroom)

The Jazz in the Classroom series of albums and study scores was the brainchild of faculty member Herb Pomeroy and Berklee administrator Robert Share in the days when jazz education materials were scarce. They tapped the best Berklee composers and arrangers to write material for studio sessions with Pomeroy’s top student big-band ensemble (later named the Recording Band). Albums were released annually from 1958 to 1981 and showcased the composing and arranging skills of budding greats Arif Mardin ’61, Michael Gibbs ’63, Bob James ’58, Toshiko Akiyoshi ’59, and others. Many players heard on the albums went on to brilliant careers, including Joe Zawinul ’59, Gary Burton ’62, Alf Clausen ’66, Sadao Watanabe ’65, Charlie Mariano ’51, Nick Brignola ’58, Gábor Szabó ’59, and more. Pianist and composer James Progris ’56 penned the closing track “I Would if I Could” for Vol. II. He later penned the keyboard method books that were required texts for all Berklee students for decades. Jazz critic Leonard Feather hailed the arrival of the Jazz in the Classroom series, writing enthusiastically that jazz “has at long last been found worthy of academic treatment and analyses on the school and college level.” —Mark Small

1959Henry Mancini, “Peter Gunn” (ft. Dick Nash)

1959

Henry Mancini, “Peter Gunn” (ft. Dick Nash)

Trombonist Dick Nash ’48 grew up in the Boston area and got his start sitting in at local nightclubs while attending Schillinger House in the postwar period. In 1953, he packed up for L.A. with a keen eye for opportunity backed by hard work and monster chops. He went on to have an impressive career as a first-call studio musician, recording with Quincy Jones, Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, and Nat “King” Cole, to name just a few, in addition to playing on thousands of film and TV soundtracks ranging from Hatari! and Roots to the 2001 Planet of the Apes reboot. Fans of the ’60s cult classics Breakfast at Tiffany’s and Days of Wine and Roses have heard Nash’s signature trombone sound—a gutsy “blatt” that gave muscle to several Henry Mancini soundtracks. “Peter Gunn,” the iconic and oft-covered opening theme to the television show of the same name, reached no. 8 on the Billboard Top 100, while its soundtrack, The Music from Peter Gunn, holds the distinction of being the first album to win the Grammy for Album of the Year. —Margot Edwards and Susan Gedutis Lindsay

The 1960s

1960Johnny Rae, “Potlicker Blues” (ft. John Neves)

1960

Johnny Rae, “Potlicker Blues” (ft. John Neves)

East Boston–born bassist John Neves was beginning a professional baseball career when he was interrupted by the Korean War and a back injury. He returned to Boston in 1954 to hit the stand at the Stable, a modern jazz club in the Back Bay. He played in the house band with pianist Ray Santisi, drummer Peter Littman, and sax player Varty Haroutunian, later joined by Herb Pomeroy on trumpet. In 1959, Neves joined forces with vibraphonist Johnny Rae, who had studied drums at Berklee before heading out on the road with George Shearing and later Herbie Mann. Along with other Boston musicians, Neves backed Rae on his first LP, Opus de Jazz, Volume 2, for Savoy in 1960. The first track on that LP, “Potlicker Blues,” is a hi-test cocktail jazz sound that is quintessential 1960s, featuring Rae’s intricate, melodic vibe improvisations. After Opus de Jazz, Rae toured for many years with several artists, including Stan Getz, Charlie Byrd, and Earl Hines. —Susan Gedutis Lindsay

1961Lionel Hampton, “McGhee” (ft. Andy McGhee)

1961

Lionel Hampton, “McGhee” (ft. Andy McGhee)

From 1957 to 1963, sax and flute player Andy McGhee toured extensively with Lionel Hampton’s band. The composition “McGhee,” from Lionel Hampton’s recording The Many Sides of Hamp, features the titular musician’s bebop-inspired alto blues. After coming off the road with Hampton, McGhee joined Berklee in 1966, staying for 47 years, until he retired in 2013. While maintaining a full teaching schedule, he wrote several instruction books, Improvisation for Saxophone: The Scale/Mode Approach, Improvisation for Flute: The Scale/Mode Approach, and Modal Studies for Saxophone. A highlight of his career was the Golden Men of Jazz tour with Hampton, Harry “Sweets” Edison, Clark Terry, Benny Bailey, Al Grey, and Benny Golson in the early 1990s. In May 2006, McGhee was awarded an honorary doctorate from Berklee. After McGhee’s passing in 2017, former student and then Woodwind Department Chair Bill Pierce remembered him as a “man of substance and integrity. He tried to impart those virtues to those of us who had the privilege to be his students.”—Susan Gedutis Lindsay

1962Quincy Jones, “Soul Bossa Nova”

1962

Quincy Jones, “Soul Bossa Nova”

If it seems like Quincy Jones ’51 has done it all in his 70-year career, perhaps it’s because he truly has. But before winning acclaim as a performer, arranger, bandleader, composer, music executive, and producer, Jones was a student at Schillinger House. He recalls it being “one of the most unique schools in the country”—and someplace he could study music while staying close to New York City’s jazz scene. A year after Jones left the school, Lionel Hampton hired him as a trumpeter and arranger. Soon Jones was arranging for Dinah Washington, a collaboration that led to work as an arranger and bandleader with Louis Armstrong, Ray Charles, and Dizzy Gillespie, among others. After leading his own jazz orchestra, Jones joined Mercury Records in 1960: first as a music director, then as the first Black vice president of a major American record company. He had his first no. 1 pop hit in 1963, as a producer for Leslie Gore’s “It’s My Party,” then composed his first film soundtrack in 1964, for The Pawnbroker, beginning a remarkably successful run as a producer and film composer. While Jones may be best known for producing Michael Jackson’s Thriller and the single “We Are the World,” his 28 Grammy Awards (and record 80 Grammy nominations) span a range of genres and roles. His tune “Soul Bossa Nova” encapsulates Jones’s genius, versatility, and longevity. In a 2010 interview with Billboard magazine, he noted: "I wrote that in 1962 in 20 minutes for the Big Band Bossa Nova album...when the bossa nova first started.” Nearly 60 years after it was released, “Soul Bossa Nova” remains instantly recognizable, having served as the theme of the Austin Powers films, the 1998 World Cup, and television programs in Canada and Germany. —Becky Prior

1963Woody Herman, "It's a Lonesome Old Town (When You're Not Around)" (ft. Phil Wilson)

1963

Woody Herman, "It's a Lonesome Old Town (When You're Not Around)" (ft. Phil Wilson)

Before he joined the faculty in 1965, Phil Wilson was a featured soloist for the Woody Herman Orchestra. On “It’s a Lonesome Old Town (When You’re Not Around),” he created of one of the most cherished trombone solos in jazz, one that kicks off with an impossibly high, siren-like wail that descends to a slow, bluesy sputter. The solo has been emulated by young players for decades. As a teenager, Tom Plsek, chair emeritus of the Brass Department, idolized Wilson, largely because of this track. “He starts on this ungodly high note, and I heard that and said…what the heck is that? …holy Jesus, that’s a trombone.” Wilson modeled Berklee’s Dues Band (later called the Rainbow Band) on his experience with Herman. “When you look at Woody Herman's band, you see that Woody ran a family-type organization for 50 or more years,” Wilson told Berklee Today in 2004. “I've also taken a family approach.” In addition to his work with Herman, Wilson wrote arrangements for the Buddy Rich Band, including the Grammy-nominated “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy” (originally written by Joe Zawinul ’59 ’91H). —Sarah Godcher Murphy

1964Chico Hamilton, “Forest Flower” (ft. Gábor Szabó)

1964

Chico Hamilton, “Forest Flower” (ft. Gábor Szabó)

Jazz guitarist Gábor Szabó ’59 left his native Budapest, Hungary, ahead of the anticommunist revolution in 1956, escaping with his guitar across the border into Austria. He made his way to America, settling in California before enrolling at Berklee in 1958. He attended for two years during which time he played on two of the now-famous Jazz in the Classroom records. By 1961 he was a member of drummer Chico Hamilton’s group, which then included woodwind player and composer Charles Lloyd. In a December 1963 session, the group recorded Lloyd’s classic tune “Forest Flower,” on which Szabó is heard harmonizing the melody with Lloyd and soloing as well as accompanying. Szabó launched his solo career in 1966 with the album Spellbinder, with Hamilton and rising jazz great Ron Carter on bass. In addition to standards and pop tunes, the disc included Szabó’s modal jam “Gypsy Queen,” which Carlos Santana later incorporated in his mega-hit “Black Magic Woman.” Szabó made two dozen more notable recordings before passing away in 1982 at 45. —Mark Small

1965Jaki Bayard, “After You’ve Gone/Strolling Along” (ft. Alan Dawson)

1965

Jaki Bayard, “After You’ve Gone/Strolling Along” (ft. Alan Dawson)

Alan Dawson’s influence, both as a drummer and educator, looms large in jazz circles to this day. A Berklee faculty member for 18 years, Dawson moonlighted as the house drummer at Wally’s jazz club for six nights a week in the late ’50s. Later, as a member of the house band at Lennie’s on the Turnpike, a revered jazz club on the North Shore, he played with some of the premier jazz artists of the era, including Jaki Byard, whose now-legendary gig at Lennie’s on April 15, 1965, resulted in two live albums on the Prestige label. It only takes one listen to Dawson’s scorching solo from “After You’ve Gone/Strolling Along” (from Byard's The Last at Lennie’s) to understand how he became Boston’s most in-demand drummer. Despite having a performance career that most musicians would envy, Dawson’s most lasting legacy is his students, many of whom—Tony Williams, Terri Lyne Carrington, Vinnie Colaiuta ’75, Steve Smith ’76, and Harvey Mason ’68, to name just a few—went on to become some of the best-known drummers in the world. "I'm hesitant to say, 'I teach drums,’” Dawson said. "I teach music, and the drum happens to be one of the instruments with which to create and communicate musical ideas.” —Nick Balkin

1966Dusko Goykovich, “Macedonia”

1966

Dusko Goykovich, “Macedonia”

Over seven decades, Bosnian-born trumpeter Dusko Goykovich ’62 has cemented his status as a giant of jazz. In 1961, Lawrence Berk offered him a scholarship to Berklee, where he studied with Herb Pomeroy. At a time when he was an in-demand player, Goykovich turned down offers to join Count Basie’s, Stan Kenton’s, and Benny Goodman’s bands to focus on his studies. As a student, he recorded with the Berklee School Quintet and Orchestra, with classmates including Gary Burton and Sadao Watanabe. After Berklee, Goykovich performed with Maynard Ferguson and Woody Herman—and wrote arrangements for both of their groups—solidifying his reputation as an outstanding big band player and soloist. Eager to record his own music, in 1966 Goykovich released Swinging Macedonia, his debut as a leader. Featuring the track “Macedonia,” the album emphasized his Balkan-influenced style and unmistakably melodic phrasing. Goykovich has shown remarkable versatility throughout his career, from big band charts and symphonic arrangements to a Brazilian-inspired album. He also worked with a who’s who of jazz that includes Dizzy Gillespie, Gerry Mulligan, Sonny Rollins, Slide Hampton, and Miles Davis. Goykovich’s work, which earned him three German Jazz Critics Awards and the Echo Jazz Lifetime Achievement Award, has influenced jazz players across Europe, the U.S., and Japan. —Margot Edwards

1967Aretha Franklin, “Respect” (Arif Mardin)

1967

Aretha Franklin, “Respect” (Arif Mardin)

Quincy Jones was so blown away by Arif Mardin’s arranging abilities that he awarded him the first Quincy Jones Scholarship at Berklee in 1958. Mardin ’61 accepted and moved from Istanbul to the U.S., where he would make his mark over the next several decades, producing and arranging some of pop music’s most legendary recordings by the Bee Gees, Dusty Springfield, Donny Hathaway, Willie Nelson, Norah Jones, and so many more. He won 11 Grammys in his career, but it was time working on the Aretha Franklin classic “Respect” that Mardin would marvel at the most over the years. “I have been in many studios in my life, but there was never a day like that,” he recalled to Rolling Stone. Franklin’s iconic version of “Respect” began life as an Otis Redding cover (it had peaked at No. 35 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1965) but based on the ideas Franklin brought to Mardin and coproducer Jerry Wexler, the team worked out a new “sock it to me” arrangement that propelled the song to no. 1 in 1967. “The atmosphere in the studio at Atlantic [Records] on 60th Street was electric,” he told Sound on Sound. “Aretha would go next door and rehearse the background parts with her sisters. I would write down chord changes and be the liaison between the control room and the musicians. It was incredible.” Mardin worked at Atlantic for more than 30 years, moving up to leadership positions, before moving to EMI. He delivered Berklee’s commencement address in 1971, and received an honorary doctorate in 1985, the year his son Joe graduated from Berklee. —Pat Healy

1968Gary Burton, “Lines”

1968

Gary Burton, “Lines”

Vibraphonist Gary Burton ’62 arrived at Berklee in 1960, the same year he made his recording debut with guitarists Hank Garland and Chet Atkins. After studying with Herb Pomeroy, he left to play with George Shearing and then Stan Getz. By the time Burton formed his own quartet, in 1967, his profile and popularity were on the rise with three albums recorded for RCA. In 1968, the year he released Gary Burton Quartet Live, he became the youngest person ever named DownBeat’s Jazzman of the Year. Recorded live at Carnegie Hall with guitarist Larry Coryell, bassist Steve Swallow, and drummer Bob Moses, the album fused jazz with elements of rock, folk, and country, with Burton’s solo on “Lines'' highlighting his groundbreaking work on the vibraphone. A major force in music education and an innovator in jazz and on the instrument, Burton pioneered the four-mallet technique that now bears his name. After joining Berklee’s faculty in 1971, he continued to release albums—nearly 70 of them—and perform regularly until his 2017 farewell tour with longtime collaborator Makoto Ozone ’83. The pianist was among many former students—including Donnie McCaslin BM ’88, Tiger Okoshi ’75, Antonio Sanchez ’97, and Julian Lage ’09—to join Burton’s noted groups over the years. His long list of collaborators also includes Chick Corea, Pat Metheny, John Scofield ’73, and Roy Haynes. A seven-time Grammy winner and NEA Jazz Master, Burton served as Berklee’s dean of curriculum and then executive vice president until he retired in 2004. —Margot Edwards

1969Sadao Watanabe, “Tokyo Suite: Sunrise/Sunset”

1969

Sadao Watanabe, “Tokyo Suite: Sunrise/Sunset”

A dusty-groove recording that plays like a Japanese Love Supreme, “Tokyo Suite: Sunrise/Sunset'' is the fourth track on saxophonist Sadao Watanabe’s 1969 Japan-only release Pastoral. This 14-minute suite evokes a Tokyo day from beginning to end: Sadao’s sopranino sax wakes us to the serene optimism of sunrise and pulls us into the rising energy of an urban day, finally lulling us back to sunset repose. Sadao ’65 was one of the pioneers of Japanese jazz since he first joined pianist Toshiko Akiyoshi's group in 1953, ultimately taking over the ensemble after Akiyoshi moved to the United States. Watanabe soon followed, attending Berklee from 1962 to 1965, where he explored Brazilian and nascent modern jazz sounds, playing with Chico Hamilton, Gary McFarland, and others. On “Tokyo Sunrise/Sunset,” he fuses the pentatonic sensibilities of both blues and Japanese traditional music. The Sunrise/Sunset performances are live and genuine, and the delivery is deep; its imperfection speaks to the authentic human experience. The music takes us somewhere—and back. —Susan Gedutis Lindsay

The 1970s

1970Michael Gibbs, “Family Joy, Oh Boy!”

1970

Michael Gibbs, “Family Joy, Oh Boy!”

Michael Gibbs ’63 is renowned as a composer, arranger, and bandleader who has worked with Peter Gabriel, Joni Mitchell, Pat Metheny, Jaco Pastorius, and many more. Gibbs left his native Rhodesia (now called Zimbabwe) in 1959 to study at Berklee, where his student friends included future jazz greats Gábor Szabó ’59, Gary Burton ’62, and Steve Marcus ’61, among others. In 1969, Gibbs’s blues-inflected tune “Family Joy” was featured on Burton’s Country Roads and Other Places album. Gibbs recorded his own version (under the title “Family Joy, Oh Boy!”) with his London-based big band for his album Michael Gibbs in 1970. In 1974, Gibbs joined the faculty at Berklee, where he was an influential teacher and ensemble leader for nine years. Returning to London after his time at Berklee, he released numerous albums and scored many movie and TV productions. Producer Narada Michael Walden hired Gibbs to pen charts for records by Angela Bofill, Whitney Houston, Stacy Lattisaw, Sister Sledge, Elton John, and others. At a 2017 concert of Gibbs’s music in celebration of his 80th birthday, Berklee presented him an honorary doctorate. —Mark Small

1971Bruce Cockburn, “One Day I Walk”

1971

Bruce Cockburn, “One Day I Walk”

As a Berklee student in the mid-1960s, Bruce Cockburn ’65 studied jazz composition(Opens in a new window) and wrote poetry on the side. Over time he merged these two passions, becoming an acclaimed songwriter, winning 12 Juno Awards, and earning a place in the Canadian Music Hall of Fame. What’s more, his enduring commitment to social justice has earned the respect of fans. Like many of his generation, Cockburn’s political consciousness was shaped by the Vietnam War. In the fall of 1965, he and his Berklee classmates were eligible for the draft. “They started with what they considered to be nonessential fields of study,” he said. “And what do you think was deemed to be nonessential? Why, art, of course—including music.” Cockburn has spent his 40-year career proving the many ways music is essential for personal, political, and spiritual growth. He encourages young songwriters to do the same. “Don’t be afraid to take on social or environmental issues,” he told Berklee students in a 1997 convocation speech. “That involvement won’t dry up your music. It will ground it and inject it with fire.” —Sarah Godcher Murphy

1972Mulatu Astatke, “Mulatu”

1972

Mulatu Astatke, “Mulatu”

Image by Mário Pires

Mulatu Astatke ’58, born in Jimma, Ethiopia, was the first African student to enroll at Berklee, where he studied vibraphone and percussion. He made his first recordings in America in 1966 in which he blended elements of African, Latin, and soul music. In the 1970s, Astatke returned home, where he became known as the “father of Ethio-jazz.” Through his collaborations with top Ethiopian musicians and his use of vibraphone and conga drums, his sound became influential in the nation’s jazz and popular music. In 1973, when Duke Ellington toured Ethiopia, Astatke played as guest artist with the band. Astatke’s eponymous tune, “Mulatu,” appeared on his 1972 album, Mulatu of Ethiopia, on the Ahma Records label. The funky instrumental features Astatke’s trademark vibes in a musical texture with tenor saxophone, horn section, wah-wah guitar, conga drums, bass, and drums. His label folded in 1975 and his albums languished until the French Buda Musique label reissued them in the 1990s, introducing Astatke to an international audience. Seven of his songs were later featured in the American film Broken Flowers in 2005. He has since completed a fellowship at Harvard and a residency at MIT working on the modernization of traditional Ethiopian instruments. In 2012, he was awarded an honorary doctorate at Berklee. —Mark Small

1973Aerosmith, “Dream On”

1973

Aerosmith, “Dream On”

Image by Daigo Oliva

Aerosmith holds a staggering number of distinctions and awards, including being the best-selling American hard rock band of all time and recipients of multiple Grammys. There’s one distinction you probably don’t know about, which is that the group is perhaps the first band to play the Berklee Performance Center(Opens in a new window) (BPC), although technically the venue wouldn’t open as the BPC until a few years afterward. The band, including Berklee alumni Brad Whitford ’71 (guitar) and Joey Kramer ’70 (drums), used to practice in the theater just before Berklee purchased it. And, who knows, maybe “Dream On,” Aerosmith’s first single to crack Billboard’s top 10 list, first found its genesis in those early rehearsals. —Bryan Parys

1974Steely Dan, “Any Major Dude Will Tell You” (Donald Fagen)

1974

Steely Dan, “Any Major Dude Will Tell You” (Donald Fagen)

Image by Ralph PH

Find a self-professed jazz snob with a taste for rock ’n’ roll, mix in dark humor, and toss it on the broad canvas of 1970s rock and you get the influential sound of Steely Dan. You also get songs like “Any Major Dude Will Tell You,” Steely Dan cofounder Donald Fagen’s tongue-in-cheek commentary on 1970s L.A. hip lingo. When Fagen ’66 and fellow cofounder Walter Becker first arrived in the city early in the decade, “dudes'' were everywhere. Amused, they did what any mildly sarcastic intellectual might: they wrote a song about it. The song was released on Steely Dan’s third album, Pretzel Logic, in 1974. Several decades later, in 2001, Berklee presented Becker and Fagen with honorary doctorates. At the event, Becker advised Berklee grads: “As you go into your musical careers, people will try to refocus you on their goals and their artistic aspirations. It’s always best to stay focused on your own. It’s the only shortcut that really is available.” —Susan Gedutis Lindsay

1975John Abercrombie, “Lungs”

1975

John Abercrombie, “Lungs”

John Abercrombie ’67 emerged from Berklee’s guitar program into a jazz world undergoing a major shift. Releases such as the Gary Burton Quartet’s Duster (1967) and Miles Davis’s genre-smashing breakthroughs In a Silent Way (1969) and Bitches Brew (1970) were entirely reimagining the relationship between jazz and rock. After a few years honing his skills as a sideman in this new space between genres, dubbed “fusion," Abercrombie struck up what would be a lifelong creative partnership with one of fusion’s original pioneers, drummer Jack DeJohnette. Together with Mahavishnu Orchestra organist Jan Hammer ’69, they released Abercrombie’s debut, Timeless, now a classic of the genre. Over his prolific 50-year career as a guitarist and composer, Abercrombie would prove restless, constantly playing with opposites: density and space, tradition and innovation, deep grooves and formless flows—impulses on display from his very first statement as a bandleader. Take Timeless’s opener, “Lungs,” an aptly named track that seems to fill itself up completely, pause for a moment, then exhale with a cool nod. —John Mirisola

1976Pat Metheny, “Bright Size Life”

1976

Pat Metheny, “Bright Size Life”

Image by Xavier Badosa

Pat Metheny was only 19 in 1974 when he moved to Boston as a member of the Gary Burton Quintet. Shortly thereafter, Burton brought him into the Berklee fold as guitar instructor. By December 1975, Metheny had recorded his debut album, Bright Size Life. The outing, a trio effort featuring veteran drummer Bob Moses and soon-to-be legendary bassist Jaco Pastorius, showcased Metheny’s lyrical improvising and compositions infused with his distinctive harmonies. As he was writing material for the album, Metheny shared his music in lessons with his Berklee guitar students. Two decades later, he returned to Berklee to receive an honorary doctorate in 1996. From the unaccompanied eight-note guitar intro of the title track to the last note, Bright Size Life took the guitar world by storm, launching the storied career of arguably the most influential jazz artist of his generation. —Mark Small

1977JoAnne Brackeen, “Fi-Fi’s Rock”

1977

JoAnne Brackeen, “Fi-Fi’s Rock”

Image by Carol Friedman

Pioneering instrumentalist, composer, and recording artist JoAnne Brackeen entered the jazz world as a largely self-taught pianist at a time when few women were on stage who weren’t singing. Starting in the late 1950s, Brackeen performed around Los Angeles with luminaries such as Dexter Gordon, and then moved to New York in the 1960s, collaborating with musicians George Benson and Chick Corea, among others. In 1969, she became the first female member of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. After spending some time in the bands of Joe Henderson and Stan Getz, Brackeen started making records as a leader, including Tring-a-Ling, her fourth album, which features the song “Fi-Fi’s Rock.” To date, she has recorded more than two dozen albums as a leader, and is featured on more than 100 others. In 1994, she joined Berklee’s faculty and today is a professor in the Piano Department(Opens in a new window). Over her career, Brackeen has won several awards, including the nation’s highest honor in jazz, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) Jazz Masters award. —Kim Ashton

1978Bob James, “Angela (Theme from Taxi)”

1978

Bob James, “Angela (Theme from Taxi)”

Image by Elxan Qəniyev

Jazz and classical pianist and composer Bob James ’58 caught his first big break when fellow Berklee alumnus Quincy Jones discovered him and signed him to Mercury Records. James then transferred from the University of Michigan to Berklee (rooming with notable baritone saxophonist Nick Brignola ’58), where he honed his chops. While his list of albums and collaborations are a mile long, one of his most enduring compositions is “Angela (Theme from Taxi),” which not only helped bring fusion jazz to the mainstream, but further set the legendary sitcom apart in the annals of television history. While Berklee wouldn’t formally establish a film/TV scoring program(Opens in a new window) until a year after James left the college, his diverse portfolio is another indicator of the versatility of a Berklee education. —Bryan Parys

1979Mick Goodrick, “Feebles, Fables, and Ferns”

1979

Mick Goodrick, “Feebles, Fables, and Ferns”

The music of Elvis Presley and Link Wray drew Mick Goodrick ’67 to the guitar as a kid. He tuned in to jazz at 15, and after learning from members of the Berklee faculty at a Stan Kenton Summer Band Camp, he set his sights on Berklee. Upon graduating in 1967, he taught at the college for four years before hitting the road with Gary Burton’s Quartet in 1972. After extensive touring, and appearing on five of Burton’s albums, he released his own solo album, In Pas(s)ing, on the ECM label in 1979. Goodrick’s composition “Feebles, Fables, and Ferns'' opens the record, which features drummer Jack DeJohnette, bassist Eddie Gomez, and saxophonist John Surman. He continued performing and recording with various jazz artists and returned to the Berklee Guitar Department in 1997. Goodrick’s teaching and innovative books on fretboard harmony have influenced countless young guitarists around the world. —Mark Small

The 1980s

1980Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, “Minor Thesis”

1980

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, “Minor Thesis”

Image by Thomas Neforas

Heard on the tune “Minor Thesis” from the Live at Montreux and Northsea album, by drummer Art Blakey’s 11-piece Jazz Messengers Big Band, are saxophonist Bill Pierce ’73, Branford Marsalis ’80 (and his brother, trumpeter Wynton Marsalis), and guitarist Kevin Eubanks ’79 (and brother, trombonist Robin Eubanks), as well as former Berklee faculty member James Williams and then-future Percussion Department(Opens in a new window) Chair John Ramsay. Blakey led the Jazz Messengers across four decades and showcased the talents of more than 200 young musicians in the process. Blakey’s sideman roster includes jazz giants Wayne Shorter, Keith Jarrett ’67, Chick Corea, Freddie Hubbard, and many with ties to Berklee. Among them are faculty members Joanne Brackeen and Geoff Keezer ’89, and alumni Donald Harrison ’81, Cindy Blackman ’80, Wallace Roney ’81, and Javon Jackson ’87. Blakey is quoted as saying: “Yes sir, I'm gonna to stay with the youngsters. When these get too old, I'm gonna get some younger ones. Keeps the mind active.” —Mark Small

1981Emily Remler, “The Firefly”

1981

Emily Remler, “The Firefly”

For most of jazz history, opportunities for women instrumentalists were, to put it mildly, few and far between. But in the late ’70s—decades before Terri Lyne Carrington ’83 dared to imagine jazz without patriarchy(Opens in a new window)—Emily Remler ’76 proved it was possible for a woman to make it as a lead guitarist in the male-dominated genre. A rock and folk musician growing up, Remler’s jazz epiphany came in her first year at Berklee when she discovered the music of Wes Montgomery, Paul Desmond, and Pat Martino. After college, she moved to New Orleans to continue honing her skills, and by 1978, jazz great Herb Ellis was hailing her as “the new superstar of the jazz guitar.” On “The Firefly,” the title track from her first album as a leader, she delivered on the hype, showing off a deep sense of swing and a knack for tuneful melodies. Though her career was cut tragically short—Remler died of a heart attack at age 32 in 1990—her legacy lives on through the people her music inspired. —Nick Balkin

1982Patrice Rushen, “Forget Me Nots”

1982

Patrice Rushen, “Forget Me Nots”

Image by Ben Alman

With multifaceted artistry and strong leadership, Patrice Rushen has been breaking down barriers for women in the music industry since the 1970s. Her funky classic “Forget Me Nots” was a top-five hit and earned Rushen the first of four Grammy nominations. (Years later the track was given new life when Will Smith used it as the basis for his Grammy-winning “Men in Black”). Rushen was the first woman to be named music director for the entertainment industry’s top awards shows, including the Emmys, the Grammys, the People’s Choice Awards, and the NAACP Image Awards. Since 2008, she has been a Berklee Ambassador for Artistry in Education, frequently visiting as a guest speaker. During the 2015 Berklee Women Empower Symposium in Valencia, Spain, Rushen extolled the virtues of studying music business in an artist-centered environment like Berklee. “You can see what (musicians) are going through,” she said. “You understand what happens when they get in front of the microphone.” —Sarah Godcher Murphy

1983Journey, “Separate Ways (Worlds Apart)” (ft. Steve Smith)

1983

Journey, “Separate Ways (Worlds Apart)” (ft. Steve Smith)

Image by Erik Kabik

The drumming of Steve Smith ’76 reverberated extensively in arenas and on the radio waves across the globe during the years 1978–1985 when he was a member of the multiplatinum-selling band Journey. The lead track of the band’s 1983 album Frontiers was “Separate Ways (Worlds Apart),” one of four top-40 singles from the disc. Journey sold more than 100 million albums worldwide over its career and soared to great heights of popularity during the years Smith was a member. The band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2017. Smith began playing jazz in his formative years; at Berklee, he studied with drum masters Gary Chaffee and Alan Dawson. In 1977, Smith was working with fusion violinist Jean-Luc Ponty before entering the rock world with the band Montrose and later Journey. After leaving that band, Smith focused again on jazz, working with the all-star group Steps Ahead and leading his band Vital Information. Smith has topped Modern Drummer magazine polls in three categories. He continues to work with various artists and is a widely hailed drum educator. —Mark Small

1984Prince, “When Doves Cry” (Susan Rogers)

1984

Prince, “When Doves Cry” (Susan Rogers)

Bursting onto the scene with his 1977 debut, For You, Prince’s meteoric rise continued with each successive album, propelled by his infectious hybrid of funk, rock, and R&B grooves and his unique guitar style. His epic sixth album, Purple Rain—and the hit movie—established him as a superstar and brought his acclaim to new heights. Prince was well-known for collaborating with and championing women artists. Perhaps lesser-known is his work with women behind the scenes. Enter producer Susan Rogers, now a professor in Berklee’s Music Production and Engineering Department(Opens in a new window). Rogers served as Prince’s recording engineer between 1983 and 1987, working on a string of hit albums including Purple Rain, Parade, Around the World in a Day, and Sign o’ the Times. At a recent Berklee event, she discussed “When Doves Cry,” revealing that the original recording was very heavy with rock power chords on guitar, and rhythm-heavy drums and bass. “He was talking about a gentle thing that has been laid low—the record was mixed, it was ready to go out the door—and he realized it just wouldn't work with these parts,” said Rogers. “So he stripped it all back and he just kept the drum machine and the main melody. It was a big career-making single for him when he had the courage to totally redo it.” Rogers subsequently worked with artists including Barenaked Ladies, David Byrne, Tricky, and Paul Westerberg. She quit the music industry in 2000 and went back to school, earning her Ph.D. in psychology from McGill University, where she studied music cognition and psychoacoustics, before coming to teach at Berklee. —Margot Edwards

1985’Til Tuesday, “Voices Carry” (Aimee Mann)

1985

’Til Tuesday, “Voices Carry” (Aimee Mann)

Aimee Mann ’80 enrolled in a Berklee summer semester knowing only a few chords on guitar, convinced that she wasn’t a very good singer and didn’t have much talent. In 2003, looking back on her decades of success—including several battles with record labels over creative control of her music—she told Berklee Today that “Berklee was a godsend for me, because to go to other music schools like Juilliard you already had to be an accomplished musician. If that had been my only option, I never would have become a musician.” At Berklee, she studied bass with faculty member Rich Appleman, met several of her future bandmates, and discovered how much she could learn if she put in the work. Mann’s band, ’Til Tuesday, formed in the early 1980s and, thanks to that work, it quickly garnered success. As Mann told the Boston Globe in 2020, “’Til Tuesday was a good band,” but “the lesson from Berklee was that practice yields great results, so we practiced all the [expletive] time.” The band’s 1985 breakthrough single, “Voices Carry,” from the eponymous album, was buoyed by heavy rotation on MTV and VH1, thanks to its audacious, award-winning music video. Carried by Mann’s dusky soprano and its ominous, melancholy depiction of a toxic relationship, the track is emblematic of the post-punk new wave aesthetic. Mann has been mostly evasive about the origins of the song, but did tell People Magazine, shortly after its release, “If a song is autobiographical, I always get the last word.” Indeed. —Robert Lagueux

1986Bruce Hornsby, “The Way It Is”

1986

Bruce Hornsby, “The Way It Is”

Image by Dave Green

Bruce Hornsby’s road to musical fame is one that many Berklee students can relate to and have daydreamed about. Discovered while playing small shows around town, he moved to L.A. and wrote for a slew of artists while slowly piecing together a band, crafting the songs that would help him break through to the mainstream. But when he got to the top of the charts with “The Way It Is”—a song reborn 12 years later via 2Pac's posthumous mega-hit “Changes—he didn’t spend his career chasing fame and its trappings. Rather, he made a career out of his musical curiosity, collaborating with everyone from Spike Lee to the Grateful Dead to Bon Iver. His journey is a master class in career sustainability, where the point isn’t to achieve success, but to keep redefining your own idea of success. —Bryan Parys

1987Branford Marsalis, “The Wrath (Structured Burnout)”

1987

Branford Marsalis, “The Wrath (Structured Burnout)”

Image by Palma Kolansky

The career of saxophonist Branford Marsalis ’81 cannot be easily defined. Since his years at Berklee, Marsalis’s musical voice has resonated through many styles and genres. Out of the gate he was performing and recording with jazz mainstays Clark Terry, Art Blakey, Herbie Hancock, Miles Davis, and more. He went on to tour and record with Sting’s post-Police band and the Grateful Dead. From 1990 to 1995, he was the musical director for the Tonight Show with Jay Leno, and appeared in several films. Marsalis has been a classical soloist with the New York Philharmonic and other orchestras, and served as composer and/or music curator for three Broadway productions. Throughout, he has led own bands onstage and in the studio. On “The Wrath (Structured Burnout),” a tune from his 1987 album, Renaissance, Marsalis effortlessly spins lithe soprano saxophone lines over an intense swing groove stoked by legendary drummer Tony Williams. Also appearing on the album are Herbie Hancock, Kenny Kirkland, Buster Williams, and Bob Hurst. In 2011, the NEA bestowed the Jazz Masters Award on the Marsalis family, honoring Branford Marsalis as well as his father, Ellis Marsalis, and brothers Wynton, Delfeayo ’89, and Jason Marsalis. —Mark Small

1988Living Colour, “Cult of Personality” (Will Calhoun)

1988

Living Colour, “Cult of Personality” (Will Calhoun)

Image by Lia Chang

There aren’t many people who can say that they sent Mick Jagger to pick up an award for them, but Will Calhoun ’86 can. Calhoun studied performance(Opens in a new window) at Berklee before switching to music production and engineering(Opens in a new window), noting that “Berklee was about more than learning notes on the page. As students we learned from each other how to hustle, play clubs, and learn a beat from Haiti or a pentatonic scale from India. For me, that was priceless.” When Calhoun’s band, Living Colour, won the 1990 Grammy for Best Hard Rock Performance with Vocal for its song “Cult of Personality,” all of that priceless learning came in handy—the band couldn’t show up to accept the award because, as Calhoun recounts, he was “sleeping on my drum cases in the back of a van” with the group while it traveled Europe. Jagger, fortunately, was available to attend the ceremony. The award was a massive coup for Living Colour, which had struggled to land a record deal with major labels who didn’t know what to make of an all-Black rock band. As Calhoun told a reporter, “One of the most frustrating things is the ignorance of people who will not admit or deal with the fact that Black people invented rock ’n’ roll.” But once on the air, the song took off. From guitarist Vernon Reid’s signature riff—emerging like a call to action after an opening audio clip of Malcolm X—to the lyrics’ meditation on charisma and politics, the song defies easy categorization. Meters are deliberately muddled, beats are dropped, genres overlap and fuse. But beneath it all, the rock solid, is Calhoun. All the more reason that his custom bass drum should be, as it is, in the Smithsonian(Opens in a new window). —Robert Lagueux

1989Juan Luis Guerra, “Ojalá Que Llueva Café”

1989

Juan Luis Guerra, “Ojalá Que Llueva Café”

Image by Keneth Cruz

Juan Luis Guerra ’82 was studying jazz guitar at Berklee—“I was a Pat Metheny wannabe,” he told Berklee Today in 2005—when an unplanned moment during a jam session led to the realization that he could make his best music by embracing the folkloric rhythms of his native Dominican Republic. After returning to his home country, Guerra began incorporating new styles into his sound: merengue, salsa, Afro-pop, and the Dominican Republic’s endemic bachata. Layering soaring vocal melodies atop energetic rhythms and nimble instrumental lines, he created an unmistakable musical style that helped earn him three Grammy Awards and 21 Latin Grammys. Yet Guerra has earned a reputation as a poet, too. “Ojalá Que Llueva Café” (I Hope It Rains Coffee), released in 1989 as the first single from the album of the same name, is a lyrical masterpiece. Inspired by his time in the impoverished northern region of the Dominican Republic, the song is a litany of fanciful but impossible events, any one of which would provide relief to those most in need. An expression of hope and our shared humanity as passionate as the romantic love at the center of any bachata, it is among Guerra’s most beloved songs, and more than 30 years later still his favorite song to perform. —Robert Lagueux

The 1990s

1990Steve Vai, “For the Love of God”

1990

Steve Vai, “For the Love of God”

Image by Luis Vasquez

Steve Vai ’79 has written that his instrumental rock ballad “For the Love of God,” from his 1990 album, Passion and Warfare, expresses “deep spiritual longing.” The six-minute piece transitions from a rhapsodic melody to unfettered shredding, a showcase for Vai’s celebrated virtuosity that earned him numerous accolades and a ranking among the best 100 guitar solos of all time. During his student years at Berklee, Vai became interested in transcribing Frank Zappa’s guitar solos, which ultimately led to tours and recordings with Zappa. Following stints with David Lee Roth, Alcatraz, and Whitesnake, and a role in the movie Crossroads, Vai embarked on a highly successful solo career. Throughout, he has maintained close ties with Berklee, receiving an honorary doctorate in 2000, and helping to create a Berklee Online course about his guitar techniques(Opens in a new window). He promoted it in 2011 with the world’s largest online guitar lesson. —Mark Small

1991Patty Larkin, “Tango”

1991

Patty Larkin, “Tango”

Image by Jana Leon

When Patty Larkin ’74 accepted her honorary doctorate at the 2002 entering student convocation, she offered the freshman class some outstanding advice. Quoting the poet Stanley Kunitz, she said, “Be what you are, give what is yours to give, have style, dare.” Larkin has done exactly this over a career spanning four decades, expressing her personal vision through sharp, insightful lyrics and innovative guitar accompaniment. “Be yourself” is always great advice, of course, but it helps if your self is “a drop dead brilliant guitar player, a richly textural singer, a commanding, poetic songwriter, [and] a hilarious and personable entertainer,” as Performing Songwriter once described Larkin. Tango was Larkin’s fourth album and the first she coproduced. The title track shows just why she has been a cherished fixture on the contemporary folk scene since the 1980s. For her most recent album, Bird in a Cage, Larkin crafted melodies for poems by America’s leading poets, including Kunitz and Robert Pinsky. The project was coproduced by the late Michael Denneen(Opens in a new window), her longtime collaborator and a former faculty member in the Music Production and Engineering Department. —Sarah Godcher Murphy

1992Dream Theater, “Pull Me Under”

1992

Dream Theater, “Pull Me Under”

Image by Dave Green

Prog metal titans Dream Theater landed a mainstream hit with 1992’s “Pull Me Under,” a minor miracle for a band known for uncompromising, radio-unfriendly opuses, often divided into sections with roman numerals. Revered for their technical ability, the band members’ legendary chops were forged in Berklee practice rooms. John Petrucci ’86 (guitar), John Myung ’86 (bass), and Mike Portnoy ’86 (drums) founded the band as Berklee students, and the group’s connection to the school has remained strong ever since. After Portnoy left the band in 2010, Mike Mangini, a Berklee professor, stepped in to replace him. In 2012, they recruited then-current student Eren Başbuğ(Opens in a new window) to write string arrangements for their 2013 self-titled album and to conduct a Berklee student orchestra and choir for the band’s epic Boston Opera House concert in 2014. In 2020, Petrucci and Berklee President Roger H. Brown announced the Dream Theater Scholarship Fund(Opens in a new window). “Berklee is something that is close to me, not only because I went there, but my son graduated there and my wife Rena has her online certificate from there,” Petrucci said. “We’re really excited about it getting started because that’s where our origins were.” —Nick Balkin

1993Melissa Etheridge, “I’m the Only One”

1993

Melissa Etheridge, “I’m the Only One”

Image by Kelly Davidson

Melissa Etheridge ’80 credits Berklee for teaching her not just music theory and history, but also how to communicate with other musicians. After three successful albums, Etheridge released “I’m the Only One,” which became her biggest Billboard hit from her highest-selling album. The song was an intentional return to her rock and blues roots, and the album’s mainstream success turned Etheridge into a household name, with her catchy rock anthems earning comparisons to Bruce Springsteen. At nearly the same time, Etheridge came out publicly as a lesbian, becoming a high-profile advocate for the LGBTQ+ community. Nearly 30 years later, she continues to use her voice to advocate for change; her activism has expanded to include the environment, opioid addiction, and cancer. In a 2014 interview with Berklee(Opens in a new window), Etheridge emphasized the value of bringing your whole self to your art: “I really think it’s important to be in your truth.” —Becky Prior

1994Lalah Hathaway, “Let Me Love You”

1994

Lalah Hathaway, “Let Me Love You”

When Lalah Hathaway recorded her first album in 1990, she was still a student at Berklee. “It was the perfect place for me,” she told Berklee Today in 2005. “I found a lot of myself that I didn’t know was there and met a lot of musicians who really shaped the way I heard music.” In 1994, she released her follow-up, A Moment, propelled by its first single, “Let Me Love You.” The dance-friendly track is a shining example of ’90’s R&B; but what sets it apart from its contemporaries is Hathaway’s mature and soulful vocal delivery—harkening back to the era of her iconic father, Donny Hathaway. In the decades that followed, she became one of the most distinctive voices in R&B, thanks to her warm, dexterous contralto and uncanny ability to sing two notes at the same time (as featured on her 2013 Grammy-winning collaboration with Snarky Puppy(Opens in a new window)). Hathaway returned to Berklee in 2012 for a performance celebrating the opening of the Africana Studies Center, a multidisciplinary facility dedicated to the study of Black music, history, and meaning. “It’s been really important to me to figure out my path…and just keep moving forward,” she told students. “The rest of it—the accolades and all of the other stuff—is a bonus.” —Sarah Godcher Murphy

1995Alf Clausen, “Señor Burns”

1995

Alf Clausen, “Señor Burns”

Image courtesy of The Simpsons™ and ©1990 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All rights reserved.

Of his 26 years composing for The Simpsons, Alf Clausen ’66 says, “I am very blessed. How many other jobs can you say that about?” As is often the case, that blessing was the result of an awful lot of persistence. After graduating from Berklee, Clausen worked a variety of music industry gigs in Los Angeles—arranger, teacher, performer, music copyist, jingle writer—before landing a long-term job on the Donny & Marie show. That led to work on The Mary Tyler Moore Hour, Moonlighting, and, yes, ALF. Then came The Simpsons, the longest-running scripted primetime television series of all time, for which Clausen wrote an average of 35 music cues for every episode from Season 2 through Season 28. Along the way, he won two Emmys and was nominated for 28 more, one of them for “Señor Burns.” Performed by Tito Puente and his Latin Jazz Ensemble, the “slanderous mambo” and its “vengeful Latin rhythm” clears Puente—in the episode, recently hired to teach in Springfield Elementary’s new jazz program—as a suspect in the attempted murder of “el diablo con dinero,” the titular, plutocratic Burns. As the lyrics put it: “Wounds won’t last long, but an insulting song Burns will always carry with him.” It’s no wonder Simpsons creator Matt Groening called Clausen “our secret weapon.” —Robert Lagueux

1996Gillian Welch, “Orphan Girl”

1996

Gillian Welch, “Orphan Girl”

Image by Hampton Taylor

On her debut album, Revival, Gillian Welch ’92 drew from the deep well of American folk music, reenvisioning established traditions to craft songs that felt her own. By some strange magic, this California girl and her partner, David Rawlings ’92, created a world far outside their own lived experience, making songs about orphans and bootleggers sound authentic and contemporary. The album’s lead track, “Orphan Girl” has the feel of a Carter family classic made personal by Welch’s soulful vocals. (Emmylou Harris recorded her own version of the song for her Grammy-winning album, Wrecking Ball.) While at Berklee, Welch studied with beloved lyric writing teacher Pat Pattison. She and Rawlings also spent two semesters together in the college’s Country Music Ensemble. “That audition was where I met Dave,” Welch said. “It is pretty hard for me to imagine a world where that didn't happen.” Though the pair attended Berklee before the advent of the American Roots Music Program(Opens in a new window), their exemplary careers have forged a path for younger Berklee alumni to follow. —Sarah Godcher Murphy

1997Paula Cole, “Where Have All the Cowboys Gone?”

1997

Paula Cole, “Where Have All the Cowboys Gone?”

Paula Cole BM ’90 has always followed her own rules, even when her choices came with costs. After studying jazz at Berklee, she turned down a contract from a jazz label, then found her own path to being a backup singer for Peter Gabriel while she worked on her first album. Her second album, This Fire—which included her first top 10 hit, “Where Have All the Cowboys Gone?”—brought her near-instantaneous fame as well as multiple Grammy nominations that recognized her talents as an artist and a producer. The pace of that level of fame proved unsustainable(Opens in a new window) and undesirable, so she pumped the brakes and focused on carving out a diverse career not just as an artist, but as an educator and mentor at Berklee, where she serves as a visiting scholar in the Voice Department(Opens in a new window). —Bryan Parys

1998Danilo Pérez, “Blues for the Saints”

1998

Danilo Pérez, “Blues for the Saints”

The résumé of Panama-born pianist Danilo Pérez ’88 reflects activities that go beyond the composing, performing, recording, and teaching undertaken by most jazz artists. Pérez has toured and recorded with such notables as Wayne Shorter, Tito Puente, Wynton Marsalis, and many more. His stint with the Dizzy Gillespie United Nations Orchestra (1989–1992) opened his eyes to how music can unite cultures. He has subsequently served as Panama’s cultural ambassador, as founder and artistic director of the Panama Jazz Festival, and as a UNICEF goodwill ambassador. His discography lists a dozen albums as a leader, including Central Avenue, named for a thoroughfare in his native Panama City. On that outing, his original tune “Blues for the Saints” blends the international language of jazz with Panamanian folk, Latin, and other musical elements. As founder and artistic director of the Berklee Global Jazz Institute(Opens in a new window), Pérez advocates for an experiential and interdisciplinary approach to help students reach their artistic potential. —Mark Small

1999Bill Frisell, “Shenandoah (For Johnny Smith)”

1999

Bill Frisell, “Shenandoah (For Johnny Smith)”

Image by Tore Sætre/Wikimedia

Iconoclastic guitarist Bill Frisell ’77 built his reputation as a jazz artist recording and performing with an international cast of stylistically diverse musicians. He surprised his jazz followers by digging in Americana territory in 1997 with his celebrated album Nashville. “Shenandoah” appears on Good Dog, Happy Man, a followup to Nashville, and is Frisell’s tribute to fellow Coloradoan Johnny Smith, who recorded a solo guitar version of the folk song in 1967. Performances with his former Berklee professor Mike Gibbs ’63, in England in 1978, resulted in Frisell collaborating with prominent European jazz artists and ultimately becoming the go-to guitarist for Manfred Eicher’s ECM label. Four decades later, his discography includes numerous collaborations and three dozen albums as a leader. In 2017, Gibbs and Frisell were onstage together again(Opens in a new window) at a Berklee concert celebrating Gibbs’s 80th birthday. The two were awarded honorary doctorates at the concert’s midpoint. —Mark Small

The 2000s

2000Wang Leehom, "Descendants of the Dragon"

2000

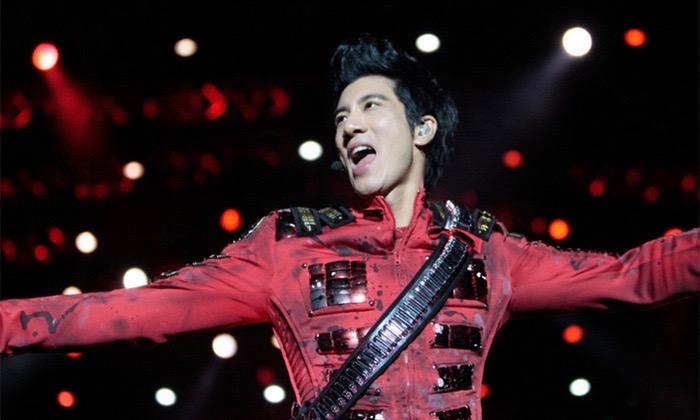

Wang Leehom, "Descendants of the Dragon"

Known as the King of Chinese Pop, Wang Leehom(Opens in a new window) ’99 is one of the most successful Mandarin-language musicians of his generation—all the more impressive considering he didn’t learn to speak Chinese until college. Born and raised in Rochester, New York, as the son of Taiwanese immigrants, he only heard Chinese at home when his parents were talking about something they didn’t want him to hear. He grew up playing violin, drums, piano, and guitar, and listening obsessively to the Beastie Boys. Chinese pop wasn’t even on his radar until his uncle Li Jian-fu, a famous Taiwanese folk singer, came to visit in the ’80s and performed his signature song, the patriotic anthem "Descendants of the Dragon,” at Wang’s house. Years later, while attending Berklee, Wang would put his own spin on his uncle’s song, blending Chinese instruments with hip-hop production, and adding a rapped bridge about his parents' immigrant experience. A massive hit, the track’s pioneering fusion of Eastern and Western elements helped change the course of Asian pop music. —Nick Balkin

2001John Mayer, “No Such Thing”

2001

John Mayer, “No Such Thing”

Image by Kelly Davidson

“I promise you are real songwriters,” John Mayer ’98 told students(Opens in a new window) gathered at the Berklee Performance Center (BPC) in 2017. “You’re just waiting on a check.” It’s precisely the advice Mayer might've given himself years prior while preparing to release his debut, Room for Squares, the five-time-Platinum-certified early-aughts phenomenon. With hints of Dave Matthews' acoustic rhythms, David Gray's wooly crooning, Stevie Ray Vaughn’s blues chops, and infectious melodies all Mayer’s own, it was an album built to accompany the listener absolutely everywhere, from the car to the supermarket to the dinner table. But in 2001, before the promotion of his first single, “No Such Thing,” Mayer was just another young songwriter full of that familiar swirl of confidence and nerves. The artist who penned those lyrics was still dreaming of future days like this one at the BPC, when he'd return as living proof of what all that time spent pursuing music was for. —John Mirisola

2002Terri Lyne Carrington, “Witch Hunt”

2002

Terri Lyne Carrington, “Witch Hunt”

Image by John Watson

When you’ve earned a Boston musicians’ union card, a full scholarship to Berklee, and a first-name-basis relationship with Ella Fitzgerald before you can even get a learner’s permit, and then become the first woman to win a Best Instrumental Album Grammy, what’s left to conquer? Injustice. Drummer Terri Lyne Carrington BM ’83, once a child phenom, is a three-time Grammy winner, an NEA Jazz Master, a recipient of an honorary doctorate from Berklee, the go-to drummer for Wayne Shorter—whose “Witch Hunt” she covers here—Herbie Hancock, and other jazz icons. She’s also a person of deep social conscience who’s used her platform to empower others. Rather than stand alone on her laurels, she founded Berklee’s Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice(Opens in a new window) and has collaborated with an all-star cast of women on her two Mosaic albums. “As much as I feel honored to have received these accolades and awards, the bigger problem is that it hasn’t happened before,” she said. Her latest album with her band, Social Science, includes the songs “No Justice (For Political Prisoners)” and “Trapped in the American Dream.” She explained, “No one is liberated until everyone is.” —Danielle Dreilinger

2003Howard Shore, “Days of the Ring” (Lord of the Rings)

2003

Howard Shore, “Days of the Ring” (Lord of the Rings)

Image by Benjamin Ealovega

How do you build a world through sound? This was the challenge put to Howard Shore ’68 when he scored Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, a book trilogy with perhaps the most complicated and fully realized fictional universe in all of literature. While Shore cites discipline as the reason he was able to complete such an undertaking, it probably helped that his career has been a master class in musical world-building. When he left Berklee, his journey didn’t look like it would lead him to becoming one of the most iconic film composers in history. It started with his jazz fusion band the Lighthouse, which opened for seminal rockers Jimi Hendrix and the Grateful Dead, and then led him to composing for media, including for a new show his old summer camp friend Lorne Michaels had created called Saturday Night Live. From there his CV could be a syllabus for a course in modern cinematic history; he’s written scores for the likes of Martin Scorsese, Tim Burton, David Cronenburg, and Jonathan Demme. The complete Lord of the Rings soundtrack took him four years to finish, runs at 13 hours, and includes the Grammy-winning song “Into the West,” performed by Annie Lennox, which appears in the latter half of the soundtrack composition “Days of the Ring.” Two decades after the film’s release, the score has taken on a life of its own; crowds from around the globe fill symphony halls(Opens in a new window) to hear performances of it. In other words, the music has become a world unto itself. —Bryan Parys

2004Ralph Peterson Jr., “Shade of Jade” (ft. Eguie Castrillo)

2004

Ralph Peterson Jr., “Shade of Jade” (ft. Eguie Castrillo)

Berklee Percussion Department(Opens in a new window) Professor Ralph Peterson Jr. came to prominence in the 1980s among jazz musicians who critics dubbed “The Young Lions,” a group that stoked a renaissance in classic bebop and hard bop music. Early in his career, Peterson played with Art Blakey’s band and later fully took over the drum chores when Blakey’s health declined. Artists such as Terrence Blanchard, Branford Marsalis ’81, the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, Betty Carter, Michael Brecker, and many others sought out Peterson’s powerful drumming for tours and recording projects. He released more than a dozen albums as a leader, including Fo’tet Augmented, on which his group Fo’tet served up an Afro-Cuban version of Joe Henderson’s “Shade of Jade.” Latin percussionist and Berklee Associate Professor Eguie Castrillo makes a cameo appearance on the tune, stoking the groove with his conga drumming. Peterson shared with his Berklee students and colleagues his knowledge of jazz and wisdom gained during his career. He died after a battle with cancer on March 1, 2021. —Mark Small

2005Susan Tedeschi, “Magnificent Sanctuary Band”

2005

Susan Tedeschi, “Magnificent Sanctuary Band”

Image by Bryan Ledgard