A Desert Rose

Rimon opened a new, modern building in 2012. Benefactor Udi Angel gifted the construction costs for the building that houses a large recital hall, classrooms, and other facilities.

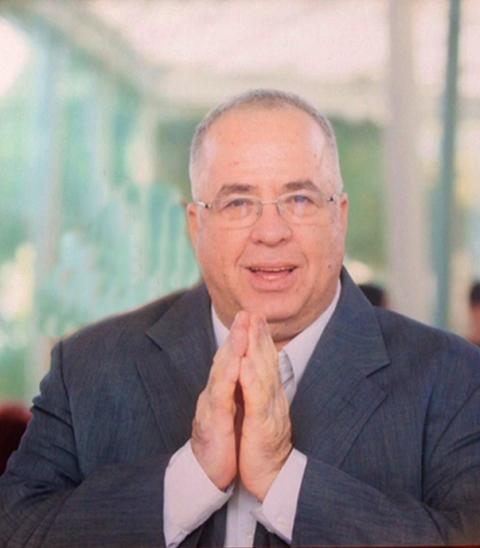

Rimon president and cofounder Yehuda Eder ’79

In the Old Testament, the prophet Isaiah envisioned a future restoration in Israel when “the desert shall rejoice, and blossom as the rose. It shall blossom abundantly even with joy and singing.” (Isaiah 35:1-2.) And it has in ways figurative and practical. In their 2009 best-selling book Start-Up Nation: The Story of Israel’s Economic Miracle, authors Dan Senor and Saul Singer noted that the tiny, now-69-year-old nation state that is home to 8 million people, “surrounded by enemies, in a constant state of war since its founding, with no natural resources—produces more start-up companies than large, peaceful, and stable nations like Japan, China, India, Korea, Canada, and the United Kingdom.” At the root of the phenomenon are high-tech innovation powered by Israel’s youth trained in technology in the Israel Defense Forces and an affinity for entrepreneurship.

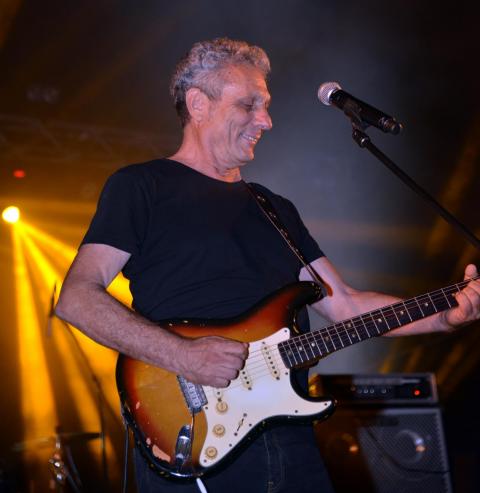

Yehuda Eder ’79, the president of Tel Aviv’s Rimon School of Music, expresses pride and surprise at the view among the press and government of his musical education endeavor. “There are many amazing startups in Israel and many people here are looking at Rimon as a startup,” Eder says, thumbing through a recent copy of Forbes magazine (the Israeli edition), which chronicled the appetite for innovation and music technology at Rimon.

“Six months ago I didn’t know what innovation meant,” Eder says, half joking. “I still don’t, but I can feel that it’s important. The whole world is communicating. Innovating is like improvising together.” Through continued growth and educational excellence, Rimon, a Berklee partner school since 1993, is responsible for much of the “joy and singing” reverberating across the desert nation of Israel and beyond. During its 32-year existence, Rimon has trained 5,000 alumni, and at most major musical events in the country, you’ll find Rimon alumni performing onstage or in technical support roles. During a nationally televised concert on May 8 celebrating Israeli independence, 28 Rimon-trained pianists played together on stage.

Orlee Sela, Rimon cofounder and current director of external affairs.

A New Season

It’s a sultry July evening and I’m in a cab heading down HaYarkon Street to the Shablul Jazz Club in the Old Port section of Tel Aviv. “Who’s playing there tonight?” the driver asks. I tell him it’s a birthday bash for rock guitarist Yehuda Eder with a group featuring some of his collaborators since his days in the band Tamuz. The driver knows of Tamuz, and that’s not surprising. Israelis might justifiably compare the career of Tamuz to those of New Radicals, Blind Faith, or the Sex Pistols. Each released but one album that was hugely influential.

Many call Tamuz’s 1976 disc The End of Orange Season (Sof Onat Hatapuzim), the best Israeli rock album of all time. It yielded two hits, but then after tons of radio play and concerts to packed houses, the group disbanded. Two members became successful singer-songwriters, others became session musicians. Eder came to Berklee to study guitar, arranging, and composition with such faculty icons as Bret Wilmott, Herb Pomeroy, and Tom Lee among others. “When I came back to Israel after Berklee, I started producing a lot of albums, but it wasn’t enough for me,” Eder says as we stroll around Rimon’s small, gated campus. “I always had this vision of students working together, that was really needed in Israel.” Working together is a cherished ideal for Eder who was raised in a kibbutz, or collective community, that farmed citrus trees in the north of Israel.

Moshe Sinai, managing director

Eder credits his wife, Miki Kam—a famous actress and singer known to TV and musical theater audiences across Israel—for fostering his dream. “I told her I was starting a school and she just said, ‘OK.’ If she had asked what I meant by that or was critical of the idea, Rimon might never have happened. I take the same approach with my songwriting students by accepting any idea they bring in. That’s the basis of creation.”

Together with six other founders, Eder brainstormed about how to build an institution that could incorporate some of Berklee’s best practices and educational methods to quench the thirst of young Israelis for contemporary music instruction. In addition to Eder, the founders included Gil Dor ’75, Guri Agmon ’76, Orlee Sela, Ilan Mochiach, and Harry Lipschitz. Amikam Kimelman ’82 came aboard later in the process but is also considered a founder. The team met weekly for two years to discuss curriculum and teaching methods. From the start, Lipschitz a songwriter and successful entrepreneur, provided crucial guidance on business matters and became the school’s leading financial officer. Eder found the location for the campus, a former elementary school in Ramat HaSharon, a suburb north of Tel Aviv. In 1985, Rimon opened its doors.

Izhar Schejter ’89, assistant managing director

“When we started, this was revolutionary for Israel,” Eder says. “There were very good academies and conservatories, but they didn’t know anything about improvising or the connections between Duke Ellington and Bach. We knew what we wanted to do; we had seen it at Berklee.”

“When we started, students who played only by ear couldn’t enter any other music academy,” Orlee Sela, Rimon’s current director of external affairs says. “We wanted to accept anyone who had musical ability even if they didn’t possess theoretical knowledge.”

“I knew we had the teachers and students somewhere in Israel,” Eder says. “The school was like a magnet. We got the very best students in the first two or three years, and a lot of them went on to become top artists, producers, and songwriters. Those students were pioneers just like we were.” The magnet also attracted a number of Berklee alumni as faculty members.

“We became known in Israel as a jazz school,” says Iris Portogaly ’89, a jazz drummer and vocalist who chaired the vocal department until becoming Rimon’s academic director in 2014. She and her husband, Ofer Portogaly ’89, met at Berklee, and their daughter Shai is a 2017 Berklee graduate. Ofer is a Rimon faculty member whose duties include teaching piano, ensembles, arranging, and leading a gospel choir. Regarding the latter, Iris states, “We don’t try to sound like an American gospel choir; we put our own soul into it. We’ve done a lot to combine local folk music with jazz and gospel styles. We have a great jazz program here, but our performance major embraces all styles.”

True enough. Rimon’s 80 faculty members lead ensembles playing jazz, pop, rock, folk, blues, country, gospel, hip-hop, electronic, Middle Eastern ethnic styles, and more. The school offers seven majors: composition, arranging, and conducting; performance; jazz institute; music education; electronic production; music production; and songwriting. Eder established Rimon’s songwriting major in 1985, before Berklee offered a songwriting major. It remains the school’s most popular major. Eder calculates that, During the past 32 years, more than 40,000 songs have been written for Rimon’s songwriting classes.

Iris Portogaly ’89, academic director

Some of Rimon’s top alumni are the biggest singers and songwriters in Israeli pop music. “Many of them are graduates of [Eder’s] songwriting classes,” Sela says. “They changed the sound of Israeli music and have written songs that are part of the people’s lives here. They are played at weddings and other occasions.”

Important Allies

Eder cites two benefactors that have provided important early and sustaining support for the school. One is Udi Angel, a top Israeli business magnate and Rimon’s board chair. “Udi approached me about producing a project for him,” Eder recalls. “Then he decided he’d donate to the school. His support has really changed things here. Another important person is Dr. Tali Yariv-Mashal, director of the Beracha Foundation. Udi and Beracha helped the school to grow.” The Beracha Foundation, an Israeli charitable organization founded by Caroline and Joseph Gruss (grandparents of Berklee trustee Josh Gruss), focuses on the environment, Jewish-Arab co-existance, and Israeli culture. In partnership with Berklee, Beracha established the Rimon Jazz Institute, which is directed by Ronen Shumelli, a pianist and 2011 Berklee graduate. The jazz institute has significantly influenced the advancement of jazz education in Israel.

A May 1992 article about Rimon on the front page of the Wall Street Journal caught the attention of former Berklee president Lee Eliot Berk. That ultimately precipitated discussions between Berk and Sela about an academic connection and transfer of credits between the two institutions. Eder keeps black-and-white photos on his phone, reminders of a visit more than 30 years ago from then-Berklee deans Gary Burton and Richard Bobbitt. Larry Monroe, acting as vice president of Berklee’s office of international programs, shepherded the agreement that made Rimon a member of the Berklee International Network in 1993. Lee Berk journeyed to Tel Aviv in 1996 to sign an articulation agreement. That established a policy for transfer of credits, which enables students to complete two years of study at Rimon and another two in Boston to earn a Berklee degree.

Harry Lipschitz, financial director

Moshe Sinai, Rimon’s managing director since 2014, was an army representative to the Israeli Foreign Ministry of Foreign Affairs and later the mayor of Rosh Ha’Ayin, a city east of Tel Aviv, for 10 years. “The connection with Berklee is a wonderful and positive model for both schools,” Sinai says. “Both sides have mutual interests to develop this cooperation.”

Sinai characterizes Rimon’s community outreach program as one comparable to the Berklee City Music Program. “Our students and faculty members go to municipalities to work with at-risk youth,” he says. “We want to empower them through music. We play music with them and inspire them. This can help them to change their communities.” Rimon recently received an award from the office of the prime minister for work in communities in northern Israel with students on the autistic spectrum. “Through music we help them develop skills to lift them to a higher level of activity,” Sinai says.

“There are a lot of high schools here that teach computer programming, and then those students enter the military and go deeper into high tech,” says Izhar Schejter ’89. Schejter earned his undergraduate degree in jazz composition from Berklee and his master’s degree from New England Conservatory of Music. He taught harmony and music business at Berklee and worked for American music software companies before returning to Israel. He’s now Rimon’s assistant managing director. “Part of the DNA of the startup nation is that people get hands-on experience with the military’s advanced systems at a young age,” he says. “We want to harness some of that by going into the high schools to teach the students about music programming. Our hope is that some will go into music technology after they finish their military service.”

Campus Expansion

From the left: Rimon School of Music founders Amikam Kimelman ’82, Guri Agmon ’76, Yehuda Eder ’79, Orlee Sela, Ilan Mochiach, Gil Dor ’75, and Harry Lipschitz.

In 2012, Rimon opened a new building, which the school’s top donor Udi Angel funded. It’s equipped with a large recital hall, classrooms, and two rooms outfitted with digital audio workstations for teaching various music technology courses. The campus also has a building with a recording studio and a basement rehearsal room where Bob Simon and a CBS television crew filmed a storied segment on the school in 1987. Additional facilities include the school’s library, cafeteria, and administrative offices. With the new building, Rimon can accommodate 1,000 students; 500 full-timers and 500 that take courses in the extension school.

The extension school—overseen by Rony Koral who is Rimon’s director of marketing—serves those who play music but aren’t considering becoming professionals. They take courses in music theory, songwriting, or music technology, and participate in the Friday jam sessions that are open to all students and led by Ofer Portogali. The extension school draws both youth and adult musicians from near and far. Among them are professionals—including doctors from local hospitals seeking to polish their musical skills.

From the left: Berklee President Roger H. Brown and Yehuda Eder. “I consider Yehuda to be my BFAM, or brother from another mother,” says Brown. “I’ve enjoyed working with him. We share a passion for music and helping young people grow as musicians.”

Rimon’s full-time students earn a diploma in three years, fulfilling part of Rimon’s original vision to create opportunities for young Israelis to study in their country and in their own Hebrew language. “Some young Israeli students who begin studying at Rimon want to continue their studies at Berklee,” Sinai says. “One way to Berklee is through Rimon’s long-standing credit transfer agreement.”

“Affordability is an issue for students everywhere,” Schejter says. “Berklee’s admissions department offers Rimon as an option for people who feel they can’t afford Berklee. The rents here are less than in Boston and our tuition is lower.” Students can complete two years at Rimon, transfer those credits to Berklee, and earn a music degree for less than the cost of spending four years at Berklee.

The newer program, Pathways, is in its second year. The program has drawn interest from participants from several countries, though to date students in the pathways to Berklee program are predominantly from the United States. “We teach the pathway students in English and use Berklee textbooks,” Schejter explains. “Everyone teaching in the Pathways Program has gone to Berklee. This provides consistency for those continuing on. We are exploring the possibilities for them to take liberal arts courses that we don’t offer online.”

Pathways has drawn students from Venezuela, Uruguay, Argentina, Italy, and Colombia, in addition to American students wanting a study-abroad experience. Many Jewish- American families want their kids to experience living in Israel, and studying at Rimon has great appeal.

Rony Koral, director of marketing

Global Visions

Schejter is working on nurturing entrepreneurial skills among Rimon’s tech-oriented students. Key figures evolving partnership are Panos Panay, founder of Berklee’s Institute for Creative Entrepreneurship (BerkleeICE), and Tali Yariv-Mashal of the Beracha foundation. “I brought Panos here to meet with people from the Beracha Foundation that supports Israeli culture and funds educational incubators,” Schejter recalls. “Both parties recognized that there was a natural connection between the foundation and what BerkleeIce is doing. Rimon became the focal point in this.” BerkleeICE and Rimon signed a memorandum of understanding [MOU] in 2016 to develop innovation labs at Rimon’s Accelerando Incubator and BerkleICE. The goal is to “broaden student entrepreneurial mindsets and career preparedness by creating environments that foster creativity, cross-discipline collaboration, and innovation with an emphasis on practical outcomes,” the MOU states. It will build on the partnerships Berklee has with Harvard, Brown University, and MIT and Rimon’s relationships with leading universities and enterprises in Israel. Among the projects and collaborations between the two labs will be semester-long student exchanges.

Eder dreams big and envisions Rimon becoming a global educational institution that will draw musicians from all over the world on its own merits. Key to reaching that goal is forging agreements that will enable Rimon issue a bachelor of music degree. To that end, Eder and his team are solidifying alliances between Rimon, Berklee, and Tel Aviv’s Kibbutzim College of Education, Technology and the Arts.

“Rimon will teach music courses, Berklee will teach music and online courses, and Tel Aviv’s Kibbutzim College will offer the required liberal arts courses for a degree,” Eder says. “David Mash [Berklee’s former vice president for innovation, strategy, and technology] made strides toward this goal before he retired. Camille Colatosti [Berklee’s dean of institutional research and assessment/graduate studies] supports the program. We are waiting for the OK from the Israeli council of higher education. After we get that, things will begin in 2019.

Israeli businessman and Rimon benefactor Udi Angel

“The council of higher education is willing to grow with us because they have seen the change we have brought to Israeli culture,” Eder continues. “It’s major that the Israeli establishment is embracing Rimon, and Berklee and Roger Brown are a very important part of that. For Rimon to be able to grant a music degree in Israel will be revolutionary and very important for the future of the school.”

“Follow the Flag”

When he founded Rimon, Eder was working outside of Israel’s education establishment. He finds it ironic that the establishment is now embracing Rimon’s educational philosophy and not asking them to depart from their original vision. Rimon is also becoming connected to industries that have no connection to music.

“We are seen as starting a new way of thinking and collaborating,” Eder says. “As a musician from my generation, you might have been considered a good rock guitar player but not a serious person. Now, all these people want to be part of Rimon.”

Dr. Tali Yariv-Mashal, director of the Beracha Foundation

Back at Shablul Jazz Club, the house lights are up, the set is over, and the crowd has dispersed into the humid night air. Wearing headphones, Eder is listening to the live-to-two-track recording of the set. He later tells me that he hopes now to put renewed focus on his guitar playing. “It’s like going back to being 20 years old again,” he says grinning. “That’s something that you can only do after you’ve completed your mission. My mission was to start a music school.” Like a rose that flourished in the Israeli desert, Rimon has become a well- established educational institution. Mission accomplished.