Rob Hotchkiss & Charlie Colin of Train on the fast track

Two members of the Grammy-winning outfit, Rob Hotchkiss and Charlie Colin, came to Berklee in the 1980s to hone their chops. Their finesse as songwriters and performers has played an important role in Train’s success. Collectively they cover guitar, bass, piano, harmonica, and background vocal chores and share an appetite for hard work with their bandmates. Train is a fairly democratic organization and Hotchkiss and Colin are team players who are fully aware that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

More than a decade of touring the world in vehicles ranging from fire-prone vans and Ryder trucks to tour busses and 747s has fostered the cohesion of a close-knit family among Train’s five members. The grueling travel schedules, constant work to build an audience, write songs, and polish their live show paid off handsomely this year when Train’s Drops of Jupiter CD attained triple-platinum status and its title cut was named Best Rock Song at this year’s Grammy Awards.

Veteran listeners may detect in Train’s sound a musical nod toward rock heroes such as the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Bob Dylan, Aerosmith, Elton John, Badfinger, Allman Brothers, and some jazz icons. No artist develops in a vacuum; each has influences. The most successful musicians are those who can take what has gone before, add to it, and still say something new. The folks at Train’s label (Columbia Records) and the millions of listeners awaiting their forthcoming album attest to the band’s distinctive voice.

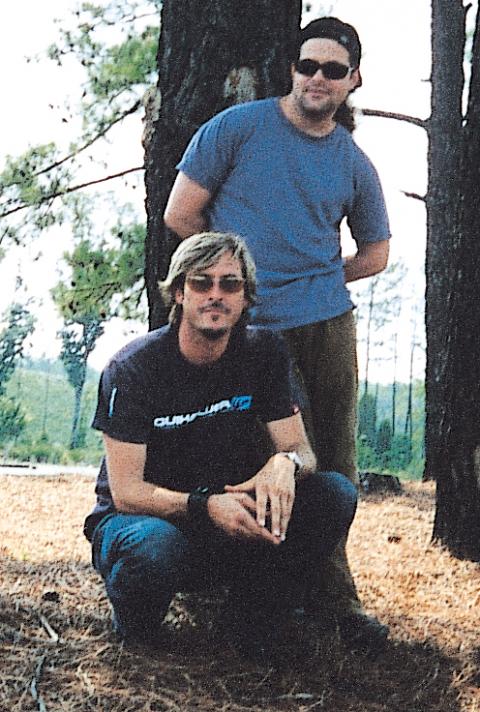

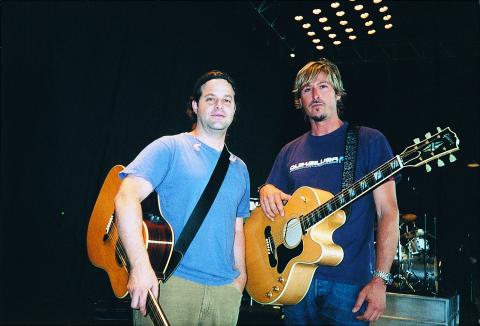

I caught up with Hotchkiss and Colin one steamy day last summer in Charlotte, North Carolina, before they took the stage at one of the stops on the Jeep World Outside Festival tour which they coheadlined with Sheryl Crow. Affable and articulate, Hotchkiss and Colin filled me in on Train’s journey from their scuffling days in California to Columbia Records and arena concerts across the globe.

Where did you guys grow up?

Columbia artist Train. from the left: Scott Underwood (drums, keyboards,percussion), Pat Monahan (lead voice, trumpet,saxophone, vibes, percussion), Rob Hotchkiss '82 (Guitar, bass, piano, harmonica, background vocals); back row from the left: Jimmy Stafford (guitar, mandolin, background vocals), Charlie Colin '88 (guitar, bass, piano, background vocals).

Rob Hotchkiss: I lived all over the place, including Berlin, Germany, for six years. My dad was in the Navy and later worked for the airlines. I also began playing guitar when I was eight. I started playing Beatles songs and then I took classical lessons until I was 13. I always wanted to play rock and roll though. Charlie and I met in Southern California and started playing together when we were in our twenties.

CC: Rob and I went to the same high school, but I am a few years younger than him. One day, someone told me about a guy who had gone to Berklee and that he was playing over at the quad. I went over there and we had a 20-minute jam. Later, when I was at Berklee, I met a drummer who said he was in a band with Rob, and I just really wanted to get into that band. That eventually happened.

How were your Berklee experiences?

RH: Coming to Berklee made me really want to do music. I remember being there learning about arranging for horns, but also really wanting to learn more about Duane Allman and slide guitar playing. I was studying with John Baboian, who is a great jazz player. I sometimes felt a little guilty about wanting to learn other styles.

Rob Hotchkiss (left) and Charlie Colin

Coming to Berklee got me totally immersed in music. I started paying some seniors to give me lessons so I could learn even more. In that atmosphere, it wasn’t unusual to practice for six hours. My routine back then was to get up, have breakfast with my musician friends, go to classes and ensembles, see bands at night, and also fit in jams on the side. It was music 24-7. I remember going out to hear players like Mick Goodrick and Bob Moses at the 1369 Club and taking the Amtrak down to New York to hear great jazz players at Sweet Basil.

RH: I also heard a lot of great players at the jazz clubs in Boston. Being at Berklee made me realize that I was never going to be the best player. You could go by the practice rooms and hear people playing who were so good. It made me search for what I had that was special. I realized that writing songs was it for me. I knew I’d never be able to play guitar as well as some of the guys I heard in the practice rooms, but I felt I could write a song as well as anybody.

CC: I had taken classical lessons as a kid too. Even though I wanted to play rock, I listened to Pat Metheny quite a bit and started listening to more kinds of music when I came to Berklee. My roommate was from Germany, and he got me listening to a lot of bands and I got really into Weather Report. I went out and bought a fretless bass and an upright. When I first got there, I wanted to play guitar like Joe Satriani. As time went on, I was going to New York to hear Avery Sharpe play bass with McCoy Tyner. That was a big shift. Ultimately, I started loving every kind of music more and caring less about becoming the best player. It didn’t matter what instrument I was playing as long as I was expressing something.

What was the first professional step you took after Berklee?

RH: Charlie, Jimmy Stafford [Train’s lead guitarist and mandolin player], and I started the group Apostles after Berklee. That band went really well. Our goal in life at that point was to get a record deal. We worked really hard in Los Angeles and got a deal with a label that was a subsidiary of PolyGram. After we did that, we realized that the deal wasn’t the real goal, things had to work out after that. Not long afterwards the label folded. We thought we had it all and then suddenly we had nothing. It was about 1993, and I knew I didn’t want to stay in Los Angeles anymore. We all had a nice little talk at the Cat ’n’ Fiddle across from Club Lingerie in Hollywood and decided that we should each go do our own thing and see what came of that. I had a hunch that we might end up back together. We did get together to record some songs and lay a little bit of groundwork for the future.

CC: We were pretty close at that point, so the split was amicable. I got an offer from some other friends to go to Singapore to write and play jingles. I stayed there for a year and did really well. It was an eyeopener for me, because I realized that I had learned enough about music that I could make a living aside from being in a band. In Singapore, I played with all types of musicians and was writing things out for them. When I came back and began playing with Train, my attitude was very different. Instead of seeing myself as someone trying to be a great guitarist or bass player, I just wanted to make the music sound as good as possible.

How did you end up regrouping as Train?

RH: When Charlie left for Singapore, I headed up to San Francisco. Pat Monahan [Train lead singer and multi-instrumentalist] and I had met while Apostles was still together. Pat had just come to Los Angeles from Erie, Pennsylvania, with a band, but two weeks after they arrived, the rest of the band packed up and went home. I had seen him perform and saw something special about him when he got up in front of an audience to sing. I thought there might be some good chemistry between us. I had been the lead singer in Apostles but was always a little uncomfortable in that role. I was more into writing the songs. Pat really comes alive onstage. I thought it might be cool to put something together with him.

I didn’t want to be in L.A. for a number of reasons though. Being there seemed to be like paying dues. So we moved up to the Bay Area, and got Jimmy to be the guitarist and Charlie to play bass. Charlie brought along Scott Underwood to play drums. With this new lineup it seemed there was more magic than we’d had in Apostles because of Pat’s voice.

Did your experience at PolyGram or contacts there give you an in with Columbia?

RH: No. When you start a new band, you are starting over. Another reason for leaving L.A. was to be away from the record industry. We knew if we started out there with the new band, there would be A&R guys at our first show. We didn’t want that because they would judge us initially and even if they saw us later when we were ready, they’d have a preconceived notion about the band. In L.A. you could play a show about every three weeks and you’d have to really work to get all of your buddies to hear you so the club would want you back. In San Francisco, we decided to play as much as possible and not care how many people came out to hear us. We couldn’t afford to rent a rehearsal space, so we looked at some of those gigs as a free rehearsal in front of a few people.

CC: Sometimes we’d do a couple of shows in a night. We’d go do open mic shows for different crowds. We got to try out new material. We were playing five or six nights each week.

RH: We got to polish the music, and we started to draw a crowd. At first there were seven, then a dozen, and eventually a thousand people coming out to hear us play. There were various labels checking us out, but 10 of them passed on us. Pat really wanted Train to end up with Columbia.

How did that ultimately happen for you?

RH: We met an A&R guy from Columbia named Tim Devine who just didn’t give up. He really believed in the band and wanted us on Columbia, but Donny Ienner [Columbia Records chairman] is very much the leader. Someone had seen the band and told him that we were the next Led Zeppelin. Columbia decided to fly us out to New York to do a showcase for an audience of industry people. We’d only been together nine months. Donny heard us and thought we were a good band, but said, “This isn’t Led Zeppelin. Let them develop a little more.” Tim didn’t want to let us go. Gregg Latterman is the president of Aware records. Tim and he decided that if we did a tour and developed a little more, in a year there would be a bidding war for us. That was a different approach to developing an act. Gregg has since done it with other acts like John Mayer, Bleu, and Five for Fighting, bringing them from Aware to Columbia.

CC: Columbia didn’t sign us until after we had made our first record, though.

RH: It was after that, that Tim signed us to Aware. It was like being in the minors. We got to go out and do the Aware Tour and see if we had what it takes to stay together when it is five guys in a hotel room and when the van catches on fire.

CC: That actually happened twice! It burnt to the ground in Nebraska.

RH: We ended that tour in the back of a Ryder truck going over the Rockies in the middle of winter. After the van burned, the only thing we could get was a truck. So there were two guys up front in the cab driving with the heat blasting while the rest of us were in the back of the truck wearing every piece of clothing we’d brought just to stay warm. I was thinking, Dad, if you could see me now! We were setting up our own gear and playing to small crowds on that tour. Those experiences make you strong.

How did radio start picking up on you?

CC: For nearly three years, we played each night and drove from town to town. We’d go to whatever radio station was there—sometimes after having been up all night. We’d show up in the morning to play and plug our upcoming show. We’d walk in with acoustic instruments and the drummer would play his drum cases with brushes. Every time, the DJs would be surprised that we could play and sing well without all kinds of equipment. Then we’d go play our show with lights and a P.A. and they saw that we could do both. This kind of thing earned us a little bit of respect as underdogs.

RH: The local radio people from Columbia were bringing us around to these stations, and they would tell their higher-ups that we were a really hardworking band. We were actually getting radio play. That is almost unheard of in the business. Usually radio play happens from the top down when someone says, “Play these guys.” We were getting it from the bottom up. By the time Donny Ienner knew who we were, we were on the way to a gold record. He figured Columbia should meet us halfway.

CC: They are really behind us now, but we worked very hard before we had their support. They appreciate that and are proud of us because it went well and they are proud of themselves for making it go over. Drops has sold over three million copies to date. We have a good relationship with Columbia. They know that if they put a lot of energy into the band, we are going to give the same effort back. We won’t whine about what they are not doing; we are going to make things happen as much as we can.

How do you approach a record with your current producer Brendan O’Brien?

CC: He does a lot in the preproduction phase. He will go through the songs and find out what is essential and what isn’t and then help to create great arrangements and parts. It is just like working amongst ourselves, but there is another member of the band who is more objective.

RH: I think we could produce ourselves, but we’d probably kill each other. You need someone who can prevail. Before recording Drops of Jupiter, we had 200 cassette tapes of ideas that we recorded in our hotel rooms, at sound checks, and on the bus after gigs. Pat went through all of them to cull what he felt was the best material. Then Brendan was able to say, “Let’s go after these ones,” or “This is good, but it needs a bridge.”

CC: In the studio when we’d say, “I can do a better take than that one,” Brendan would say, “No you can’t. You’re not going to do any better than that take, it had good energy.” He helped us not to obsess over each part. You can make each take perfect and end up with a record that is full of tension. He kept us from trying too hard. So the music sounds fresh, because we didn’t do more than a few takes and we’d keep some of the early basic tracks. There is a bit of honesty to working like that.

RH: On Drops of Jupiter, I left the development of my parts until the end, because I didn’t want to have them all worked out. I’d be coming up with stuff and then tell Brendan that I was ready to do a take. He’d say, “You’re all done; you got it. I was rolling tape all along.”

What was it like to win the Grammy?

CC: It was a big honor just to be nominated and asked to perform. We got five nominations. We figured since we’d been asked to play on the show, it might be a consolation because we weren’t going to win. We were going up against such enormous acts, it didn’t seem possible that we could win over a band like U2. After we played, we were standing backstage and heard them announce the winner for Best Rock Song. They said our names, and we flipped out. It was surreal. We really didn’t expect it.

We shared a room backstage with the Dave Matthews Band. We have passed each other on the road, so there was this real camaraderie, no jealousy or competition. That night was a big celebration of tenacity. If you hang out long enough, things will work out.

With the touring schedule you’ve kept up, when do you get to write new material?

RH: We write songs everywhere.

CC: We toured to support our first record for about three years. First it came out independently, and then a year and a half later Columbia put it out. We were on tour the whole time and did all of the writing for the Drops of Jupiter CD on the road. Pat was always there with his tape recorder. Now we all have Pro Tools rigs and can record in the hotel rooms or on the bus.

When we were touring the same record for three years to get to where Columbia would support us, we would do different things with the material. We would play the song so that everyone could recognize it, then we might open it up for a drum jam or introduce Latin rhythms and elements of jazz. The songs wouldn’t be the same every time. Because we can play in different musical genres, there is a wide audience for us. We have young kids who are also listening to Widespread Panic, but their parents like our music too.

How do you feel about all the travel you do?

RH: This tour with Sheryl Crow is easier than some past ones have been. We are only playing four shows per week.

CC: It got a little out of hand in 1999 and 2000. We were touring 11 months out of the year. I couldn’t keep a relationship together, and I put my stuff in storage because it didn’t make sense to keep my apartment. At that point, you can kind of unravel. Now we have adequate time to recover from long tours.

A huge perk of being at this level is that we don’t stay in the same spot. For the first three years, we just toured the United States and Canada. The last couple of years we spent a lot of time in New Zealand, Australia, Mexico City, and Europe. We get to hear other bands and play with lots of musicians. When we stay someplace for two or three months, we pick up a lot of the culture. We came up with a lot of good ideas in Spain that will come out on the next record.

What are your hopes for the new CD and beyond?

CC: We all love melody and beautiful music, whether it is the Beatles or Tchaikovsky. We are not thinking that we’re weird, avant-garde artists trying to write a tune for radio. I don’t expect to have a song like “Drops of Jupiter” on every record. Every single thing that could go right for it did go right, allowing the song to become a massive hit. I am grateful that things went the way they did, but I’d like to see the next record be appreciated as a whole rather than just one or two songs.

It is a privilege to be at this point, and we all know it. We can’t help but be workaholics. If we decided to take two years off, I know we couldn’t come back and be in the same situation we are in now. We have to stay at work all of the time. There is pressure in that, but there is also complete elation with it. There is a family vibe in our band. I love these guys. I’m doing what I’ve always wanted to do. I never get confused about it.