Antonio Sanchez Speaks of Now

Antonio Sanchez

For Antonio Sanchez, the last year and a half has been a dream and a blur. After a lengthy audition process, Pat Metheny asked him to become a member of his Grammy-winning band in the spring of 2001. It was both a great break and a daunting prospect for Sanchez, who was well aware that Metheny has worked with many legendary jazz drummers. Metheny really knows what he wants from a drummer, and his music is sophisticated, subtle, and deep. Almost immediately the Pat Metheny Group (PMG) went into the studio to create the Speaking of Now CD. The music was unrehearsed and brand new to everyone and PMG's methods for capturing the best performance were also new to Sanchez. Happily, everyone loved the results.

Next on the agenda was bringing the music to the world. For most of 2002, the band traversed Europe, Asia, and America before ending triumphantly with a pair of sold-out concerts in Antonio's hometown, Mexico City, Mexico. The enthusiasm of those audiences was overwhelming to Metheny who had never played in Mexico before. Metheny attributes part of the attention PMG received to his reputation and part to Sanchez as the hometown boy who made good.

Sanchez, grandson of Ignacio L—pez Tarso, one of Mexico's most famous film stars, grew up playing rock and didn't seriously listen to jazz until he enrolled in Mexico's National Conservatory of Music. He later transferred to Berklee, where his unique and highly virtuosic style of jazz and Latin drumming coalesced. He was one of those Berklee students who peers and faculty members sensed was destined for a great career. Not surprisingly, he had to miss his own graduation because he was touring Europe with Latin jazz saxophonist Paquito d'Rivera.

Since then, doors have continued to open to Sanchez. He has played and recorded with such jazz artists as Avishai Cohen, David Sanchez (no relation), Danilo Prez, and Miguel Zen—n. In a way, Sanchez has been spoiled after working with Pat Metheny, whose rabid international following and elaborate concert productions are without parallel in the jazz world. But judging by Metheny's enthusiasm for Sanchez's drumming (see sidebar on page 13), he won't be hustling a new full-time gig for some time. How old were you when you took up the drums?

I started playing when I was five. I was interested in rock and used to play to albums by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. Eventually, I began listening to Rush, the Police, and other groups with great drummers. By the time I was about 17, I could play along with the guys who were my idols. I was a rock and roll guy and pretty naive. I thought I knew everything I needed to know about drumming so I decided I'd study piano when I entered the National Conservatory. There was a jazz workshop at the conservatory that has since become a degree program. I met a bunch of drummers there who started telling me about different players I should check out. I hadn't heard any of them before, and I was blown away when I saw videos of Steve Gadd, Dave Weckl, and Vinnie Colaiuta. I wondered how they learned to play like that and figured out that I still had a lot to learn on drums. I realized then that I didn't really know very much.

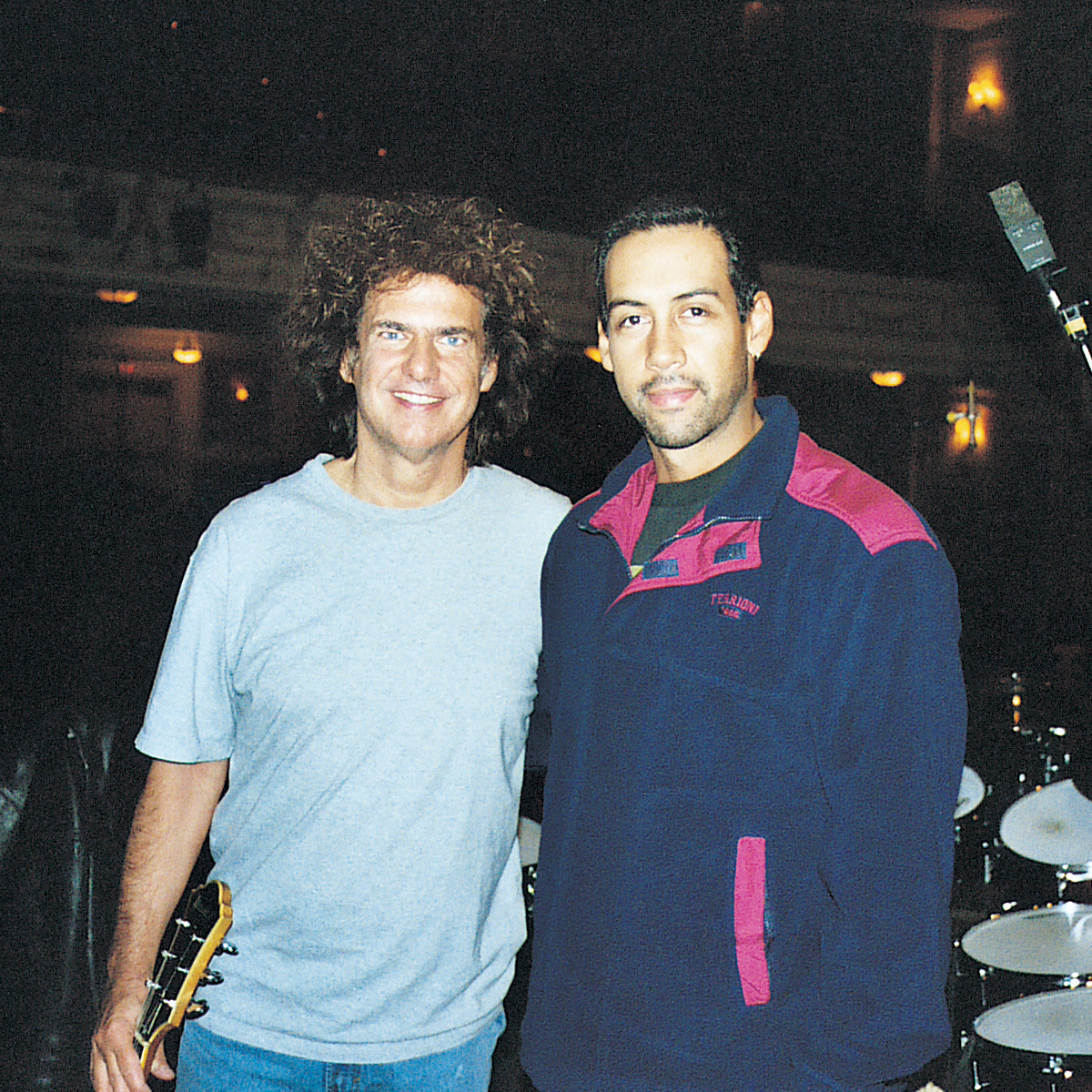

Antonio Sanchez and Pat Metheny

Were you self-taught, or had you studied with a teacher at that point?

When I was young, I had studied with a jazz teacher all along, so he had showed me proper technique with the traditional grip. I wasn't ready for jazz at that point. I remember when, during my rock and roll phase, my mother tried to get me to listen to an Art Blakey record. As it played, I was thinking, this is horrible: no backbeat, and the tuning of the drums makes them sound so old! Consequently, I didn't deal with jazz then. Now, years later, I'm trying to figure out what Art Blakey and other jazz drummers were doing. Is jazz popular in Mexico?

It is not really a big thing down there. But even in America, it is not easy to find jazz. It is not like you can turn on the television or radio and find people playing it. In Mexico, you have to make the effort to hear it and find out about it.

Had you heard much of Pat Metheny's music back in Mexico?

Yes, I listened to a lot of his stuff there. Back then, I didn't think his music was that demanding or complicated for the drummer compared with the music I was listening to. I liked his stuff, but I was into really complicated, virtuosic music. Now that I am playing it, I realize that Pat's music is all of that and more. It is very demanding because of all the subtleties in it. I didn't realize before how much work it would take to get to where I could play his music well.

How did you decide to come to Berklee?

After realizing at the conservatory that I had a lot more to learn about drums, my mom kind of pushed me. She knew that I was very persistent and that there wasn't much other than music that interested me. She told me that if I was going to do it, I should shoot for the big time and do it right. A friend I had met at the conservatory named Rosa Avila was also a drummer. She left and went to do the one-year program at the Musicians Institute [MI] in Los Angeles. When she finished, she took a gig with Andy Williams and she'd gotten endorsement deals with Zildjian and Pearl Drums. She came back to school, and we all thought this was great. I applied to MI and to Berklee and was accepted to both. I didn't want to come to the U.S. for only a year, that seemed too short. Berklee had a much more thorough program and so I chose that.

Were you a performance major?

Yes. It was hard for me to adjust at first. I had been getting into jazz, so I knew all of the guys I should listen to. I hadn't played much jazz, but I thought I could play it. After banging my head against the wall for a while, I started getting a feel for what jazz was supposed to be.

Did you meet friends at Berklee that you still see from time to time?

From the start, I was very focused on what I wanted to play. I would seek out the best musicians at the school, and I would eventually play with them. I have stayed in touch with my Berklee friends. Not long ago, I did a recording session with bass player Christian Bausch '96, saxophonist Bill Vint '96, guitarist Sean Driscoll '95, and keyboardist Patrick Andren '95. I ran into Patrick when PMG played in Sweden. I travel so much now that I get to see a lot of Berklee people.

Were there any teachers who were especially influential for you?

All of them had an influence on me somehow. My first drum teacher at Berklee was John Ramsay. He showed me the ABCs of jazz drumming. He gave me so much stuff that I should still be working on. All of my drum teachers, Jamie Haddad, Casey Scheuerell, Ron Savage, Ed Uribe, and Kenwood Dennard were influential in their own way. Hal Crook was another great teacher. Victor Mendoza has an eye and ear for up-and-coming talent. Many students who played with him have ended up with really good gigs. He picks you out and works with you for a while until you are ready to go to the next level. He helped me a lot.

What led to your first professional gig after you finished at Berklee?

I had played with Danilo Prez in a workshop at Berklee. He used a student band that I was in with Fernando Huergo '92 and Renato Thoms '95. Danilo called me to do some gigs in Panama. He also recommended me to Paquito d'Rivera who was looking for a drummer. Later, Paquito's management called me for a European tour with the United Nations Orchestra, and I flipped. This was in 1997, just after I finished Berklee, and I didn't know if I was ready.

Where did you become exposed to so many styles of Latin music?

I was lucky to grow up in Mexico. We are close to the States, the Caribbean, and South America. We get Latin influences like cumbia, salsa, you name it, in addition to American music. I heard tons of music growing up. At Berklee, I had to work as much as I could. The peso had fallen to half its value against the dollar, so it was very expensive for me to attend Berklee. I was playing anything in those years: reggae, soca, salsa, and with wedding bands. So when Paquito's gig came along, I had no problem with the various styles.

| The thing that blew my mind the first time I heard Antonio was that I'd never heard anyone play that soft and that simple. He had such a great touch. He was playing in a jazz trio with pianist Danilo Prez, and I heard them play a couple of ballads. It was beautiful but burning. I immediately thought Antonio was a great musician, someone who really listens. Then about three tunes later, I had gone backstage and could still hear them playing, only now I thought I was hearing additional percussionists playing along too. I went out and saw that it was just Antonio doing his ferocious cowbell thing along with everything else. I thought, "Wow, is this the same guy?" It was impressive. I heard him about two weeks later in a club and was impressed again by his dynamics and musicality. It wasn't until I had gotten together with him to play that I learned that he had ridiculous chops. It's the ultimate testament when you don't discover that until you've heard somebody play several times. He has all of this stuff that he can play, but Antonio is all about music. The drum chair in this band is a hot seat. The requirements for this gig are very specific and very broad at the same time. At the core of it, the drummer has to be a fully formed, conceptual jazz musician who understands orchestral music and is comfortable playing a number of different styles. It is really about making each moment come alive through an improvised gesture. I got together a lot with Antonio wondering if he was the guy. I finally realized that he'd be able to meet the standard for this gig. Very quickly, he took things to another place - a very personal and exciting place for the audience. He is a full-fledged member of the front line onstage now. It is such a relief for me to have someone taking it to the degree that he does. It is thrilling to get on the bandstand with him every night. You just can't wait to play with him. - Pat Metheny |

I did have a problem with experience though. It was my first big gig. [Faculty bassist] Oscar Stagnaro was in the band and helped me a lot. I thought I was going to get fired the first night. I was fine on the first two tunes. Then in the third one, I heard Paquito say something, but I couldn't make it out. The rest of the band switched from playing a samba to swing. I tried to follow and got so lost that I didn't know where [beat] one was. Oscar started yelling "one" and stamping his foot, and Paquito was looking around wondering what was going on. I thought I blew it. After the set, I went to hide out; I didn't want to look the other musicians in the eye. Before the next set, I went up to Oscar and told him I was really sorry. He said, "Sorry for what?" I said, "Because I screwed up." He said, "It's okay. Everyone screws up." From then on, I paid very close attention to Paquito.

After that, in the fall of 1997, I was in New York with my mom. Danilo was rehearsing and we stopped by. Danilo's drummer wasn't there, and he asked me to play. His manager came in, asking Danilo what he was going to do without his drummer Jeff Ballard, who couldn't make three gigs they had booked in Paris. Danilo turned and asked me if I would do the gigs. The next spring, his manager called me for more dates. It was a hard gig, because it was a trio and Danilo is very demanding. My trio chops weren't where they needed to be, but he gave me a break and worked with me until I got to a level that made everyone happy.

Wasn't it on one of those gigs with Danilo that Pat Metheny first got to hear you?

Yeah. It was at the peak of our trio playing. We had done a long European tour and were on a double bill in Torino, Italy, with Pat's trio. Pat likes to be the opener on those gigs, so he played first and then we played. We were doing the sound check and since Danilo's trio was last up, we did the first sound check. As I played, I could feel someone watching me from behind. I turned around, and Pat was there smiling. He introduced himself, and we talked. He stayed after his gig for ours. Apparently he liked it a lot.

A few months later, I was playing with Danilo in London at a club called Pizza Express and Pat was playing in town at the Barbican. He came to our gig after his. He heard our second set. Afterwards, we talked a while and he gave me his e-mail address. When I got back to New York, I contacted him to say thanks for coming by; it had been an inspiration. He sent back this long message mentioning everything he liked about the gig. He also asked me if I wanted to play the next Thursday. We got together at his studio in New York for four and a half hours. It was just a duo, Pat and me. We talked and went out to get something to eat, and he mentioned that he was looking for a drummer.

He checked me out for a few months though. We played together a couple times a week, sometimes as a duo and sometimes with a bass player. He would ask me to show him what I would do on a certain groove. He'd say, "Okay, that was good, but now try this with your left hand and be softer with your foot." He wanted to see how well I followed directions and if I could come up with parts he liked.

When he invited me to play a trio gig with him and Steve Rodby in upstate New York, he didn't mention that he wanted to see how Steve and I would sound together. We had a really good hookup, because Steve is such a solid bass player. A little while later, he had Lyle Mays come to New York and the four of us played. Then we played with some of the band's sequences. It was a long process, almost a year before he finally asked me to join the band. It became official in the spring of 2001.

Did you tour with the band before you made the Speaking of Now CD?

No. Once I was in the band, Pat told me that we'd be recording in May of 2001. He was really busy producing Michael Brecker's Ballads album, and after that he started writing with Lyle. They were writing the music until the day before we started recording. We showed up at the studio after only hearing demo CDs of the new tunes. How did the group approach recording the CD?

We went into the studio and did a tune a day. We had charts and would record the tune and then listen back to it. We would make changes, record it again, and then listen back again. By the end of each night, we had a pretty good idea of what the tune was about. Generally, we'd come back in the morning and record the tune three times. Usually, one of those was the final take and we'd begin rehearsing another tune. Generally, we did one tune a day like that, but we did two tunes on some days, completing all nine of them in seven days. I wish we could record the album again now after playing the music so much.

There are a lot of metric modulations in some of the material. How did you work out a complex tune like "The Gathering Sky?"

We used a click track for everything. In this band, the click track changes a lot because the tempos change. Pat and Lyle wanted the click to follow a human feel more than to lead the musicians. So the click would speed up or slow down. The tune "You" is a ballad that has rubato sections, ritardandos, and accelerandos, and all of that is with a click. It was so hard to follow that they put a computer monitor in my drum booth so I could see ahead of time when it was going to slow down or speed up. Now we play it easily, but at that point it was hard to learn.

"The Gathering Sky" slows down and speeds up and has a lot of challenging metric things. When we play it live, I take a big drum solo and then we come in on the last section. "Proof" was another difficult tune - it's really fast. When we play live, the tempos are even faster. The click is set to a faster speed for playing live. It's funny: when you are tired, the tempos seem really fast; and when you have lot of energy, they feel slow, but the click is the same each night.

Would you say the metric modulations and playing with the click while trying to make the groove feel natural are among the harder aspects of playing Pat's music?

Not really. I think the most challenging part is the dynamics. Pat is so meticulous about the dynamics and wants the songs to have a natural build. On some songs, for instance, I start with brushes, then I go to rods, then to sticks, then to bigger sticks. That's all to make the build feel completely natural. The average listener probably would not notice it, but everyone can feel the music rise. To play every section at the right dynamic level so that it makes sense in the overall picture is what I consider to be the hardest thing.

It is difficult for most drummers to play quietly with intensity, but you are very comfortable playing at a whisper.

I think that is one of the things Pat liked when he heard me playing with Danilo. I trained myself to play super soft, because Danilo's group was a piano trio. At a lot of the gigs, we didn't have monitors, so if I played a little louder than I should, I couldn't hear the piano at all. I learned to play with a lot of dynamic control and to play really fast tempos at a low volume. When I came into Pat's band, I started using in-ear monitors. We are not using floor monitors, so I'm not feeling the room as I did before. My concept of playing has really changed because of that. It is like playing with headphones. Now I've learned to judge what level I need to play at, but when I started, I was either too soft or too loud.

What is the best aspect of working with PMG?

It is such a consistent band in many ways. Starting with the crew, they set everything up so precisely every night. To have shows as we do where nothing goes wrong is amazing. It is also unbelievable to play with such great musicians every night. Since they are so consistent, I had to become really consistent too. After a while, you can take that for granted. When you go back to playing in other situations where the level isn't as high, you start wondering, "Why are these players messing up?"

When you are playing almost every night for a long tour, some nights you feel so tired you wonder how you will ever get through, but you have to. This is my job, and people pay a lot of money to hear the group. I have to give them my best performance.

When Pat offered me this gig, he said, "Everyone can have an off night except for you." When the drummer has an off night it affects the whole band. But now, after playing this music so much, even if I was to have an off night, Pat might not be able to tell. The sets are very long. That must be an endurance test for a drummer.

We have played as long as three hours and 40 minutes without a break. In the beginning, Pat was trying to put together a set that would represent different stages and the history of the band. He said he wanted the set to be like one long tune that made sense from beginning to end. Now the show is just over three hours. Even though there are lots of dynamics in the music, we still play hard and loud. I wasn't used to that at the beginning. No gig could have prepared me for it. In a rock band, you play really loud and hard but the music doesn't have the intricacy. The ride cymbal playing in this band is brutal. If I could get a machine to count how many times I hit the ride cymbal, it would probably come out to a couple million hits a night. That's because some of the tempos are so fast. For my first couple of weeks in the band, my arm was hurting. I told Pat about it, and he said, "You'll be fine." Once we got the set down to three hours and 15 minutes, it felt like a breeze. This has been an amazing experience.

Do you want to put out an album as the leader?

Definitely. I used to write a lot before I started going out on the road this much. I let it go, because after playing with musicians like Pat Metheny, John Patitucci, Danilo Prez, and David Sanchez, my tunes didn't sound that good to me. Those guys have such a command of composition and harmony. I'm starting to write again because I have a lot of ideas that I want to work on. Maybe next year if I am not too busy, I will try to put something together. Next year, I am doing my first concert as a leader for a jazz festival in Mexico, and I will write material for that. I've also gotten to know lots of great musicians that I could invite to play on an album now.

Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

I'd like to be a first-call drummer for tours and for recording with a number of people. Basically, I want to continue what I've been doing, but advance it even more. I know that takes time. I have been really lucky that in such a short time I've gotten to play with a lot of great people. There are so many excellent musicians in New York who have been there for years paying their dues. I feel in a way I have to pay some more dues. I have learned a lot by working with Pat, but I know I have much more to learn as a sideman before I become a leader.