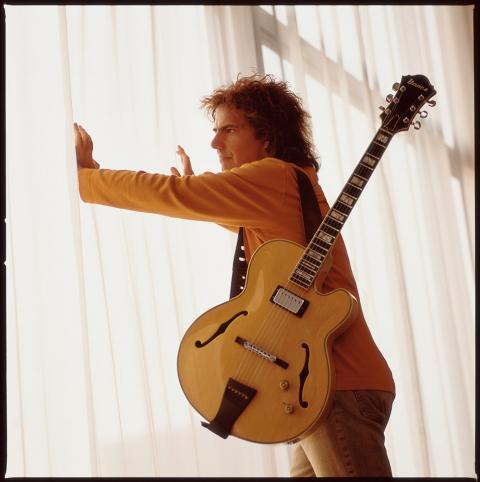

Pat Metheny: No Boundaries

Pat Metheny

During the three decades of Pat Metheny's mercurial career, numerous journalists have used a lot of ink to describe his wide-ranging musical output. To date, Metheny has released 30 albums that have netted 16 Grammy Awards in nine different categories. The sheer number of wins ties him with Sting and Aretha Franklin in the roster of top-10 all-time Grammy winners. He is in a class all by himself however for winning trophies in jazz, pop, rock, instrumental composition, and other categories. Through the years, Metheny has created critically acclaimed recordings with such diverse artists as Herbie Hancock, Jaco Pastorius, David Bowie, Steve Reich, Ornette Coleman, and of course, the Pat Metheny Group.

Metheny's 16th Grammy statuette was awarded for his 2003 solo guitar album One Quiet Night, which won for best new-age performance. In a recent conversation at his Manhattan rehearsal studio, Metheny shrugged off the significance of the diversity of his awards. His stature as one of the most influential guitarists and composers in contemporary music owes something to his sense of music having no boundaries and many other factors he mentioned in our wide-ranging discussion.

Growing up in the 1960s in then-rural Lee's Summit, Missouri, Metheny came to believe that stylistic categories were unimportant in music. "I was just a fan of music, and I didn't know that there were differences in style," Metheny says. "To me, music was music; it was just one big thing. The Beach Boys, the Beatles, Miles Davis, and Ornette Coleman were unified by the fact that their records were mixed together on the shelves of the little drugstore in our town. There were no different sections. Back then, there were musical things that I liked and wanted to learn, and they really jumped out at me. I never made much distinction about style. That's still sort of true."

Trial by Fire

Although he will turn 50 this August, when Metheny arrived on the scene he was hailed as a prodigy. He began playing trumpet at eight and switched to guitar at 14. After he started jamming with players in the Kansas City area, he began getting calls for gigs. "That changed my life and gave me an incredible head start. In my early days in Kansas City, I was fortunate to have been taken under the wings of some of the best players. Paul Smith was the piano player in a group led by a trumpet player named Gary Sivils. I sat right by Paul's left hand and would watch the bass notes and his voicings. I already knew the basics of harmony, but I didn't know too many tunes. Watching him play was probably the best instruction I could get.

Another guy, an organ player named Russ Long with whom I played a lot, would intentionally run me ragged. Once he figured out that I didn't know a tune, he would always call it. After I learned it, he'd never call it again. He also played very fast tempos and played the tunes in weird keys. It was trial by fire, but it was great for me. "Another local musician named John Elliot was a great pianist and teacher who had a very unique way of thinking about harmony in terms of parallel keys and bitonality. The guys from Kansas City played mostly by ear. Even chord symbols back then were not standardized. It wasn't until I began playing with Gary Burton that I learned about the modes and got a formalized view of harmony. When I saw Gary give his basic lecture on jazz harmony in about 1973, it was the first time it all became clear to me. I'd never heard anyone describe chords and note choices with such depth and clarity."

|

|

| (From the left): Mike Stern '75, Jay Azzolina '76, Mitch Coodley '75, and Pat Metheny performing together at the 1975 commencement concert at the Berklee Performance Center during Metheny's stint as a faculty member. |

No Bluffing

Before his encounter with Burton, Metheny spent a year in Miami and made new and important connections there. "I left Kansas City after graduating from high school. I need to add here that mine was sort of a 'mercy' graduation. I hadn't taken a book home since I started playing gigs, but there were only a few subjects that I couldn't schmooze my way through. When I was a senior in high school, a guy named Bill Lee, who was dean at the University of Miami, heard me play in a club and offered me a full scholarship to go there. That brought an incredible sigh of relief from my parents because they didn't know what was going to happen with me. I was only too glad to take the scholarship because I knew some other musicians who were involved with that school. When I got there and went to History 101 the first day, I felt all but illiterate. I knew there was no way I could bluff my way through college. I was only a student there for about two weeks. After that, I started getting involved with the music scene; and within a few days, my new best friend was Jaco Pastorius.

"That year, the university offered electric guitar as a principal instrument and went from a few guitar majors to about 80. After I told them that I couldn't make it as student, I was offered a job on the music faculty because I'd had quite a bit of playing experience. I taught for one year. During that time, I went back to the Midwest to play at a jazz festival. Hearing that Gary Burton was on the bill helped me decide to drive to Wichita to play. Later that summer, we both taught at a band camp and after that, Gary invited me to come to Boston to teach at Berklee. I think he was checking me out as a possible candidate to be in his band then, too. So I moved to Boston in 1973.

"The year that I spent in Miami was when what is identifiable as my style began to emerge. It became further refined while I was in Boston. I had never seen so many guitar players as I saw there. I didn't know what to expect when Gary said he wanted me to teach the top 30 of the hundreds of guitarists at the school. I admit I was a bit puzzled, yet I did have a lot of experience playing that other 19-year olds didn't have. What I'd learned on the bandstand at an early age was a huge advantage."

From the left: Mike Stern '75, Jay Azzolina '76, Mitch Coodley '75, and Pat Metheny performing together at the 1975 commencement concert at the Berklee Performance center during Metheny's stint as a faculty member.

Metheny's style and goals became even more focused during Metheny's tenure at Berklee and during the three years he spent as a member of Burton's band. "That period was a very important for me on many levels. When you are 19 or 20 years old, everything moves at a velocity that you will never experience again in your life. I really encourage kids that age to practice 18 hours a day, stay up all night playing music with their friends, transcribe anything that they like, and take every gig that comes along. It is a period in life when you can make enormous progress in short periods of time. It was that way for me."

Communication and Illumination

"Some of my first students at Berklee were really good players - including Mike Stern who studied with me for six years. I felt there were ways I could help these guys by communicating about real-world playing situations. In fact, most of the music that was on my first album, Bright Size Life, was written as exercises for my students during that first semester. [A number of the album's songs appeared in the first edition of the Real Book. The tune "Unity Village" appears as Exercise 6.] I wanted to illuminate aspects of harmony and other things that I was curious about as an improviser that I couldn't apply in standards. During that same period, I would call Jaco to come up for gigs around Boston. It was a very interesting time. There was a lot going on in Boston then. Things that players were experimenting with were quite revolutionary at the time. Now they are almost taken for granted."

Being a member of Burton's quintet alongside guitarist Mick Goodrick, bassist Steve Swallow, and drummer Bob Moses further shaped Metheny's musical voice. "Not only were those guys master players, they were very individual conceptionalists - as was Jaco. In my estimation, that may have been the last period in jazz where that was important. In order to exist in jazz then, you had to be a good player, you also had to have a concept and identity - a sound and vision of what jazz could be. It wasn't enough to be a second- or third-generation copy of someone else. That was drilled into me back in Kansas City, but it crystallized as I stood next to Gary each night onstage hearing him play in such an individual and virtuosic way. All of the guys in the band were completely original. So I figured I had to come up with a concept, too.

"The idea of creating a unique identity in jazz has gotten clouded over the last 20 years. Now people feel that to play well is enough. It wasn't enough in the 1970s and I don't think it's enough now. It's not even half the battle. You need to develop a sense of artistry and be able to communicate something. You have to render in sound something that is meaningful to you as an individual that might be of interest to someone else. Gary, Swallow, Moses, Jaco, and others did that naturally. It was just part of who they were as musicians."

| "I still enjoy playing tunes from the Bright Size Life album. They still feel current and viable to me. I have never felt like any one direction I've explored was no longer relevant. To me, it's all still going on." -Pat Metheny |

Apprenticing with the Blacksmith

"When I was in Gary's band, if I wasn't communicating in the way that those guys did because I was so young, I would hear about it! Sometimes we would have meetings after the gig where Gary would talk to me for hours about developing ideas, what notes to play over what chords, time, dynamics, and pacing. These are the things now that are essential to who I've become as a musician. In his very generous but rigorous instruction, Gary was like a blacksmith pounding into shape what was emerging in my musical identity. It was great for me; but at the same time, after three years, both of us knew it was time for me to move on."

Metheny wanted to go on to another sideman position; but in 1977, fusion music dominated, and both his sound and playing style did not fit the bill. "Most of the guitar gigs involved playing loud in a rock-oriented context and involved soloing over one chord. Even now, I am not interested in vamps. It doesn't matter if it is a John Scofield vamp or a Miles vamp or a Weather Report vamp; I know what is going to happen. Things are going to start soft and get louder and busier. It's been that way for 30 years, and I'm just not that interested. So after leaving Gary's band, I was kind of forced into doing my own thing." Metheny's 1975 trio debut for the ECM label, Bright Size Life with Jaco Pastorius and Bob Moses, put him on the map with music fans and critics alike. The 1977 follow-up, Watercolors, featured Metheny with bassist Eberhard Weber and future Pat Metheny Group members, drummer Danny Gottlieb and keyboardist Lyle Mays. It was the first recorded collaboration between Metheny and Mays and contained the seeds that would soon flower when Metheny, Mays, Gottlieb, and bassist Mark Egan joined forces to become the Pat Metheny Group.

Incredible Rapport

"When I met Lyle Mays, right off the bat we had an incredible rapport," says Metheny. "I had a little momentum going after winning a few jazz magazine polls as 'talent deserving wider recognition' and the previous records I'd made were well received. When I started the band, I was able to pay Lyle $30 a night, and Danny Gottlieb and Mark Egan $25 each. We were earning between $100 and $400 a night. I took the money that I'd saved from working with Gary and from when I had a paper route as a kid and bought a van and Lyle's polyphonic Oberheim synthesizer."

Metheny and company began to tour in May of 1977. They criss-crossed the country in the van taking every gig that came in. Metheny remembers one week when they played in Seattle on a Thursday, Dallas on Sunday, and Quebec City on Tuesday and took filler gigs at points in between. With few breaks, Metheny essentially stayed on tour in the United States and abroad until 1992. "I want to let young people who read this know that I still believe that anyone who has something really strong musically and is willing to go out and play hundreds of gigs for little or no bread has a very good chance of developing an audience on their own terms. I meet a lot of jazz guys who are sitting around waiting for the phone to ring. It didn't work back in the 1970s, and I don't think it works now. You have to get out there to make something happen."

And things did happen. The group's eponymous debut recording, (which Metheny often refers to as the White Album) initially sold 150,000 copies - a runaway hit in the jazz world. "That was a shock to me," Metheny says. "If someone had walked up and hit me with a two-by-four, I wouldn't have been any more stunned. What we were doing wasn't much different than what we'd been doing on the road. We were scuffling, we weren't packing them in anywhere, and were mostly opening for other artists, but we always got a good reaction. There was a groundswell of interest, and it was moving beyond the world of jazz. That too surprised me because it was never our intention to reach beyond the jazz audience. We just wanted to address areas like musical form and dynamics and the other things we had explored on that record. It became very successful and went on to sell several hundred thousand copies. That took everyone by surprise - especially me."

New Territory

One of the many appealing aspects of the group has always been Metheny's multifaceted and very personal style of guitar playing. Throughout his teens, Metheny had been steeped in jazz, but the catchy guitar textures he heard in songs on the radio by the Byrds, the Beatles, and other groups also affected him deeply. When he started out, many idiomatic guitar sounds and techniques were not utilized in jazz. The Pat Metheny Group's concerts have always featured the leader playing a variety of six-string acoustic and electric guitars, 12-string and nylon-string guitars, as well as guitar synthesizer. "No one had really explored the textural aspects of guitar playing in jazz," he says. "I began a process of trying to expand the role of guitar in jazz that is ongoing. Guitar had a lot to offer the music. The whole idea incorporating these sounds in a small group in an orchestrational and soloistic fashion is a big part of what I've been working to address for years."

While recording the White Album, American Garage, and As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls, he highlighted these sounds, it wasn't until his 80/81 album that Metheny prominently featured wild acoustic guitar strumming and finger-picked selections in the company of jazz stalwarts such as Jack DeJohnette (drums), Dewey Redman and Michael Brecker (saxophones), and Charlie Haden (bass). "That was new territory," Metheny says. "Having the guitar function in a rhythm section that way and join in the polyrhythmic aspects of drumming through strumming had not been applied much in jazz before that. I am still very interested in exploring it further."

Another drawing card for Metheny's music is the material that Metheny has written alone or in collaboration with Lyle Mays. It is difficult to dissect the music and determine just why the compositions themselves have such widespread appeal. Many have noted Metheny's gift for creating memorable melodies and linking them to unusual harmonies that go beyond the jazz vocabulary.

"Years ago when I was at the University of Miami, I realized that there were certain areas that I was interested in as a player that I couldn't get to by playing the blues, standards, or even advanced tunes like Wayne Shorter's. The things that I wanted to play were not being represented in the music that I was able to find, so I started writing my own. The first real tune I wrote was "April Joy" around the time I was turning 18. That set up this zone that I wanted to explore as an improviser. The tune wound up on the White Album. Once the group started, the idea of writing music for the sake of exploring compositional avenues really blossomed."

Audience members saw imaginary places and stories in Metheny's music and a number of film producers felt Metheny's music was perfect for soundtracks. Of the movies he has scored, The Falcon and the Snowman (1984) and A Map of the World (1999) are noteworthy, and selections from each still appear on the band's set lists from time to time. "It seems that early on, there was an element in my music that I wasn't really aware of. People felt it had a cinematic quality and evoked imagery. That wasn't intentional; the music just came out that way. It was a surprise when people started asking me about scoring movies. It was an area that I had been interested in, and I am still interested in it.

"I did eight or 10 films and for the first couple I was just happy to get through it and not get fired! It's very stressful, high-pressure work. And it is a job where you can be at the whim of people - like the director's wife or the second director's cousin - who have no idea what they're talking about. All of them have influence on whether what you are writing is deemed acceptable or correct for the film. Yet ultimately your job is to satisfy the customer.

I went into film scoring somewhat spoiled because I was used to creating my own universe on my own terms. I think all of the people I've done scores for would say I did a good job and satisfied their needs. But after a while, I started to think, 'Gee, I can spend the next three months on tour and make a record, or I can score this film.' These days, I pick the tour and the record."

Musical Inevitability

Metheny will release his 31st album, a new Pat Metheny Group outing, later this year. While some might think that the more music a person has written, the easier it becomes. Metheny says having written so much makes it harder, forcing him to dig deeper to find not only new ideas but the right ideas.

"There are certain kinds of resolutions, harmonies, melodies, and ways of improvising that, for me as a player, are perfect examples of the things I love most about music. Some of the choices in a piece like 'Map of the World' couldn't go any other way. The piece has to go that way. That quality of inevitability in music is what I really respond to. Certain things make some music very compelling to me as a listener, and they are prerequisites for gaining my enthusiasm. Oddly, most jazz does not have that for me, but when I think of the music that has it the most for me, it's jazz. It doesn't occur that often in jazz, but it does happen in the music of Miles, Wayne Shorter, Sonny Rollins, and the other greats; I find the compelling qualities - that inevitability - there in abundance. It's rare in jazz, and a lot of jazz just goes in one ear and out the other for me. It almost doesn't matter if the players are great if it doesn't have qualities that say to me this music could only go this way. That's universal in all the music that I love."

To Metheny, the spiritual side of his music - that which connects with the soul of the listener - is both the most important and least quantifiable element. "We can talk about melody, rhythm, and chords all day, but in many ways none of them really matter. What does matter is the effect that music or any human endeavor can have on other people. For me, that's what it is all about. It's about trying to manifest in sound the qualities, ideas, and features that are the good things that make being part of life on earth such a privilege. Trying to come up with things that accurately reflect the details of what I've seen and experienced has been more of a focus for me than the process of how you do that. The point of all this is to offer to others the same things that I have gotten as a fan of music. You give them a mirror to find something about themselves through what you offer. There is a quality that some music has that accomplishes that. With instrumental music, jazz, classical, or other music, since there is no text, people can really find things in it. Instrumental music transcends every language and is very international. I think the best instrumental music offers people a real window into something that they can't find elsewhere."

Metheny has created a large body of work encompassing 30 albums so far and composed more than 200 pieces. However, he doesn't spend much time thinking about the contribution he's made to contemporary music. "I don't allow myself the luxury of looking at that," he says. "Maybe someday I will, but I'm in the middle of it now and don't feel able to assess anything in those terms. The issues that I've been concerned about as I've tried to learn music over the years have remained fairly consistent. There are some musicians who do one thing and then move on to something different. That hasn't been the case for me. I still enjoy playing tunes from the Bright Size Life album. They still feel current and viable to me. I have never felt like any one direction I've explored was no longer relevant. To me, it's all still going on."