Timeless American Tales

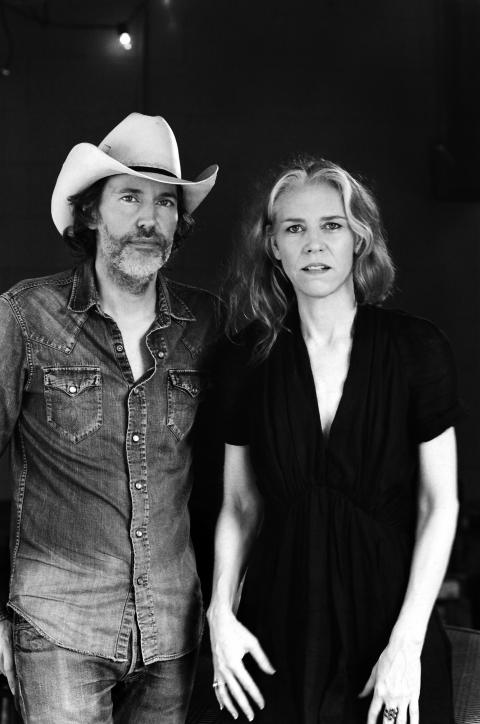

Berklee alumni David Rawlings and Gillian Welch '92

Henry Diltz

Critics wax poetic about the timeless quality of the music Gillian Welch '92 and David Rawlings '92 have created during their 20-plus-year career. Their oeuvre—seven albums and a few EPs—showcases their seamless blend of American folk and traditional musical forms with elements from contemporary music and culture. Those struggling to pigeonhole their style toss around descriptors such as bluegrass, alt-country, neo-traditional folk, Americana. Imperfect monikers aside, what's crystal clear is that the musical team of Welch and Rawlings has developed a compelling and distinctly American musical persona.

Their voices harmonize effortlessly on their tales of orphan girls, a first lover, the evils of the bottle and morphine, or yearning recollections of childhood in the Dixie of a bygone era. Their melodies are sung to pithy, deftly crafted lyrics that somehow sound deceptively simple.

While acoustic guitars are ubiquitous in traditionally based music, the sonority of their acoustic guitars (plus banjo and harmonica, occasionally) stands out from others in the field. Rawlings weaves chromatic guitar lines and ringing campanella scale passages together with jabbing, closely voiced diads over generally diatonic chord progressions. Seeking to approach the sonic realm of the dobro or mandolin, Rawlings plays a 1939 Epiphone arch-top acoustic guitar—an atypical choice for folk-oriented music. All of these elements combine to bring the music of Welch and Rawlings down from the Appalachian mountains of yesteryear to the current era.

Welch, who majored in songwriting (a protégé of Pat Pattison), and Rawlings, who majored in guitar performance, met while auditioning for the only country music ensemble that Berklee offered in the early 1990s. After they both graduated in 1992, they headed for Nashville, where some of their favorite music had been made—albeit decades earlier. Traditional music archetypes the Stanley Brothers, the Carter Family, the Blue-Sky Boys, and Monroe Brothers, as well as contemporary icons Bob Dylan, Neil Young, James Taylor, Paul Simon, and others had made deep impressions on Welch and Rawlings.

Once in Nashville, Welch began performing under her own name with Rawlings backing her on guitar and harmony vocals. While they always appeared as a duo, they opted to maintain the name “Gillian Welch” for their act. By the middle of the 1990s, they were in the studio with lauded producer T Bone Burnett who produced their first two albums, Revival and Hell among the Yearlings. In 2000, Burnett invited them to collaborate with him on the soundtrack to the movie O Brother, Where Art Thou?. Welch served as the associate producer, cowrote a song with Burnett, and sang in duet and trio settings with Alison Krauss and Emmylou Harris. A huge success, the album has sold 8 million copies to date and netted four Grammys—including one in the Album of the Year category for which Welch received a statue.

Three Gillian Welch albums followed with Rawlings as producer and sometimes engineering. In 2001, they founded their own label, Acony Records, affording them complete artistic and administrative control over their music.

Of the five Gillian Welch albums, three have received a cumulative four Grammy nominations, including one for Rawlings when 2011's The Harrow & the Harvest album was nominated in the Best Engineered Album category. They have also released two albums as the David Rawlings Machine: A Friend of a Friend (2009) and Nashville Obsolete (2015). Rawlings is the primary singer for the group, which includes Welch plus additional musicians. Welch and Rawlings tour frequently in America and abroad as a duo and with the band.

Together and separately, Welch and Rawlings have worked onstage or in the studio with a range of stars from the musical firmament: Solomon Burke, Paul Simon, the Decemberists, Ralph Stanley, Levon Helm, Willie Nelson, Ryan Adams, and Steve Earle, to name a few.

While Welch and Rawlings are known for authoring dark, heartbreak songs, they revealed sunny personalities in phone interviews for this story. And why not? The career they have built on their own artistic terms has earned them the admiration of fans, accolades from the music press, and industry awards.

Welch and Rawlings are engaged in a lifelong journey traversing America's highways and byways, cities and backwaters, introducing the past to the present with words and music.

Berklee alumna Gillian Welch '92

Henry Diltz

Gillian, when did you write your first song?

G.W.: When I was five or six, I wrote poetry—usually about nature and birds. I started making up songs and keeping a songwriting notebook when I was around 10. By the end of high school, I had written a number of songs, but I didn't play them for anybody. When I got to college at [the University of California] Santa Cruz, I was still shy about playing them in front of people, but started to perform publicly a little bit. That's when I changed from the visual arts to music. Before, visual arts were what I did and music was just to entertain myself. After getting a bachelor of arts in photography, I flipped things.

When I was 22, I took a year off and traveled around outside the country. My parents were getting worried that I wasn't going to come back. Partly as a lure to get me home, they told me that if I was interested in music, I should go to school and study it. They offered to pay for it, so I came back and attended a summer program at Berklee. I was totally self-taught before that, and the summer program got me up to speed so I could continue. The things that I learned at Berklee that I use on a daily basis are the ear training and the vocabulary that enables me to communicate with other musicians. The songwriting classes were also important for me. I had never really analyzed [songwriting] much; my ear just told me what I liked. It was wonderful to have a toolbox and know the names of the tools.

David, when did you start playing the guitar?

D.R.: I started when I was about 16. Things came to me pretty quickly. I had been playing about two years by the time I came to Berklee. Right after high school, though, I went to the University of Richmond for a short time on a scholarship. It hadn't dawned on me then that I wanted to choose music for my living, but I took all of their music classes and burned through their entire music curriculum in two semesters. I took harmony and counterpoint there so that when I came to Berklee I was able to place into some higher harmony and ear training classes. But in my playing, I felt I had a lot to learn to catch up to the other guitarists.

When I was young, discovering that music could be your life was like a revelation to me. At Berklee, I was a performance major because by then I knew I wanted to play guitar on stage for a living. I studied with Lauren Passarelli in the beginning and Jim Kelly toward the end of my time there. I also took classes with Tom Szymczak, Charlie Chapman, and Bob Harrigan. I was amazed that you could go and sit in a room and work on some aspect of guitar playing and they would consider it college. There were amazing teachers and curriculum. At the time, I don't think there was another place that had that approach.

I got to play at a couple of the commencement concerts. I was out of my league with some of the other musicians, but I'd had a lot of performance time onstage. There was a lot of stuff you learned in live performance that you didn't learn any other way.

During your time at Berklee, there wasn't a large curriculum for American roots music.

G.W.: Back then there were only three things: Mike Ihde's country guitar styles class, Bob Stanton's fingerpicking class, and—most important in my world—Bob Stanton's country ensemble. Dave and I had both auditioned for that during my first year at school, but neither of us got in. The next year, we tried again and got in. That was the audition where I met Dave. We spent two semesters in that ensemble. It was pretty fortuitous. It is pretty hard for me to imagine a world where that didn't happen.

What initially attracted you to traditional American music?

G.W.: When I heard the Stanley Brothers and other old-time music, I was really drawn in by how tough it sounded. I had grown up around punk music, but I didn't play it because I have an aversion to loud sounds. I like to listen to it, but I don't turn it up loud. When I heard the Stanley Brothers, I was struck by how tough and gnarly the music was on acoustic instruments. That was the brand of folk that moved me. I didn't like the pretty and warbly folk music, I liked the mountain stuff.

I had attended a hippy grammar school where we were taught folk songs and sang them together every Friday. When I discovered recorded folk music and bluegrass, the artists were singing all these songs I'd known since I was five.

D.R.: I wasn't exposed to old-time music as a young person. When I think of what was on the radio when I was a kid, I liked story songs and how country music found its way into pop in the '70s. I remember hearing the Doobie Brothers song “Blackwater” and thinking it was so rootsy. But that's because of what was playing on the radio on either side of it. Now, it sounds like the slickest thing I've ever heard. It is hard to imagine that now when through the Internet, it's so much easier to trace your way to what you like. Back then, the journey was a slow one. You kept your ears open and when you heard something you liked, you tried to find it and hoped it might lead to something else.

How did your chromatic approach to playing the guitar evolve?

D.R.: There are certain tones that appealed to me long before I played an instrument. Later, I became aware that there were certain tensions that I liked, so I started learning where they were on the instrument. I found if I wanted to play the ninth on an E minor chord, I didn't like the way it made everything feel unless I was playing it against the flat-third above it or the root below it, something to pull it towards the key. If you create a minor second, it's going to be dissonant to some people's ears. But that dissonance never bothered me. Why I like it, I don't know. It wasn't that I heard a certain kind of music and wanted to play like that. I heard little things like that in a lot of different music I'd listened to over the years.

As we started playing music that's based in a tradition, I began to hear that there is actually a lot more chromaticism and tension than people may think is in that music. You kind of have to know where to listen for it. In the music of Frank Proffitt and Dock Boggs, or the acoustic blues that I was interested in, there is a ton of tension and rubs with things that are going on between what they are playing on the banjo and the singing. The Stanley Brothers have a track where they are singing a big E minor triad up high and Carter Stanley is wailing on an E major chord below on his guitar, and it just goes by. That's the stuff that hit my ear. When I was at school I learned about the tensions and used that knowledge as a guide as I tried things.

Did you come to Nashville determined to do only the music you wanted rather than try to fit the mold of what was trending in town at the time?

G.W.: Kind of, but only because I was never a person who had a very broad skill set. I am a shining example of specificity: I do this one thing. Lots of other people came to town and got jobs before I did because they were more versatile and commercial. But it has been interesting. Over the years I've come to appreciate that it's good to be kind of peculiar. You stand apart from the crowd. I came to Nashville because I felt creative ties to this place. Dave and I joke now that the music that we felt tied to was long gone by the time we got here. We liked music that was 30, 40, or 50 years old, but there were still vestiges of it. Some of the people who were on those records were still here. It was really meaningful that we could go hear Bill Monroe, Ralph Stanley, Don Helms, or Scotty Moore playing in town. It was so rich that those people were around. Now, after devoting a couple of decades of our lives to this music, we are starting to feel like a link in the chain.

Did you scuffle a bit before hitting your stride in Nashville or did you do writing sessions with others once you got there?

G.W.: It was mostly Dave and me working together and developing that creative relationship. There was no grand plan. I did write with others when I got here, but it never felt very natural. What pushed me toward working with Dave was that it was a very natural working relationship. At first, I would finish every song. I was the writer, he was the picker. He agreed to go play with me at these writers' nights.

We would work hard on the arrangements. Duo music is great if you arrange it intricately. We learned that from listening to the brother teams. Their stuff was arranged. If there are only two people, you have to use every textural shift at your disposal and every vocal acrobatic that you can do to broaden the sound. That's when we started to develop a sound. A lot of the old music we loved had a lead and a tenor [singer]. Because I was the higher singer, we had lead and baritone. It sounded different, not like the other duet teams.

In listening to your music, it's sometimes hard to figure out which voice is on top.

G.W.: There are moments when Dave will shift above me or do unison with me, as we did on some verses in songs on The Harrow & the Harvest. That's our old-time version of double-tracking. Dave came up with that, it's a unique texture, arresting.

Two people singing together either have something or they don't. The first time we sang the Stanley Brothers song “Long Black Veil” in Dave's kitchen, we found that our ranges matched up. Dave's range is only a whole step below mine. He's got a big range and is a high singer. So our ranges are close together.

Are you the primary lyric writer?

G.W.: It's probably still true that I write the bulk of the lyrics, but we really are a songwriting team. Everything is better because we work together. So it's hard to quantify what “primary” means because there is a big difference between an unfinished, unsatisfying song and a satisfying finished one. Only one thing may need to be changed to make it all work, and Dave may make that change.

The same is true for the music. Dave will have more of a handle on melody and harmony and do more of the arranging. But I may make the last change that solves a problem. It goes both ways. I am happy to say that we really enjoy working together as a songwriting team.

Do you employ the same writing process for the David Rawlings Machine albums where he sings the leads?

G.W.: The writing and the problem solving involve the same process. Machine gives us another outlet creatively and stylistically to do stuff that suits him. Even though people say when they hear us they can't tell who is singing what part, as a lead singer, he is quite different from me.

Berklee alumnus David Rawlings '92

Henry Diltz

Do you find that the David Rawlings Machine and your duo present different musical challenges in concert?

D.R.: With the Machine, we are still looking around for what we do in the arrangement that is the most exciting to us. It's nice to have low notes, fiddles and other instruments, and ganged vocals. Sometimes when we are onstage and focused and it comes down to a whisper, that dynamic range is the most exciting thing. You can achieve really interesting things with a duo, but you have to work really hard to do it. There is a challenge to make it fill up the space and make it what we want. The thing we try to do that is the modern part of our music is to create panoramas and space with our instruments. Some of the earlier traditional duet records are [arranged] with a rhythm guitar with a lead guitar on top of it. I don't hear them in a panoramic way. If we aren't doing something that seems cinematic on some level as soon as our guitars start, we are not that interested in it. The challenge of coming up with new stuff is trying to get that space to happen.

At times, your song lyrics seem to hark back to an earlier era. Was it a combination of the older musical styles as well as the time period that drew you in?

G.W.: To me, the time period is melded with a kind of universal timeless language that I love. It's not so much about being in another era but being in a time where things were more fundamental. An attraction of folk music is its ability to be changing and unchanging at the same time. I feel that Dave and I started to really understand that with our third record, Time (the Revelator). We started to use timeless quality to root things in the tradition and express what was going on with us. Yet, it had a peculiar folk language.

Your songs feature characters like Annabelle and Caleb Meyer who seem like they are from a previous era. But then you'll add references to songs by Taj Mahal or Steve Miller, and mention a surfer party or everything being for free.

G.W.: It's like when a player brings out a phrase from a dead musician in a solo, some listeners will get it and it will enrich that moment. But others aren't going to get it, and that doesn't really matter. But it proves to me that the more you know, the deeper you can go.

It must be fun when your younger fans discover what some of these references mean.

G.W.: They are like little landmines that go off later down the road. That happened with me too when I was listening to Dylan at 19 or 20. I thought he made up all those words and melodies. Then years went by and I saw where some of these things came from. A line like, “The railroad men just drink up your blood like wine” comes from the folk tradition, songs that have been crafted over 150 years. We will never know who was the first person to say that, but it's a damn-good line!

You've stated that you reexamined your songcraft in between Soul Journey [2003] and The Harrow & the Harvest [2011]. I hear some different chord choices and lyric themes on Harrow. Was that a time of exploration when you were seeking out new things?

G.W. Yes, it was a time of deep exploration. Things are cyclical, and I feel like we had made a big circle and come back around. Soul Journey featured every [configuration] but the duo. There were some solo songs, and we felt that we needed drums on some of the other songs on that record. There were similarities between making The Harrow & the Harvest and our first record, Revival [from 1996]. After all that time and struggle, we knew that The Harrow & the Harvest was going to be strictly a duet record with nothing else on it but Dave and I sitting and playing together live. We felt like we'd been away from the duet format for so long. We wanted to return to it to see how we felt about the music in its most stripped-down form. We had pent-up angst and gusto for the duet stuff when we got to Harrow.

Dave had also gotten to a new place with recording techniques for that album. I was so proud for him when the album got a Grammy nomination as the best engineered album. That's not a folk category, it's all-in. I'm hands-off with the engineering process.

Did working on O Brother, Where Art Thou? open some doors for you two?

D.R.: The additional awareness in the mainstream for what people call traditional music lifted boats for everybody. O Brother was right on schedule. It seems that every 20 years, the country is ready to look at its traditional music and some compilation like that will come along. Before that, it was Will the Circle Be Unbroken by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band.

So it was good for us in that way. I certainly think that having a few million people buy a record that had Gillian's name on it was a good thing. When T Bone Burnett was approached to work on that project, he had just finished producing two records for us and I had brought in Ralph Stanley records for him to hear. When the Coens asked him to do O Brother, he immediately approached Gil to be the associate producer of the record. He then bought a ton of CDs and started poring through them. We were a good resource. T Bone knew of the Stanley Brothers, but he didn't know that Ralph was still alive and working until he was producing our records. In the overall cultural zeitgeist, that project did shine a light on the music and on us as performers.

There was a certain connection to the music that we loved that ended up being part of that compilation. The fact that it all went out into the world and that it had touched our music might have made some people hear our music a little differently or understand it a little more. It is hard to ever know, but those years would have been very different for us without that [soundtrack]. We ended up working on that project for a year or a year and a half and doing some of the scoring for the film with T Bone in the studio. We didn't end up doing any of the [follow-up] tours with the other musicians on the soundtrack because we were in the middle of writing the songs for our third record.

Is there a new Gillian Welch album in the works?

G.W.: It's in the writing stage. We have a little more domestic touring to do for the Nashville Obsolete album first. So I am here writing. I've got my notebook on the table.

Do you two have any long-range goals?

G.W.: There are always many projects, but at the moment, writing is the top job for me. We've also been working to get our entire catalog on vinyl. That's a passion of ours. It's on the horizon and is very exciting.

You tour America and in Europe, Australia, and elsewhere. Have you been surprised to find people outside this country flocking to hear your brand of traditional American music?

D.R.: I'm pleased that the music is appreciated there. There is a quality in traditional music that has made it possible to cross cultural boundaries and appeal to people in other places. Our popularity seems to be in places where English is widely understood, places where there are cultural similarities. There is a certain melancholy in what we do and in a lot of American folk music that fits well in Scandinavia where they have an appreciation for the blues and melancholy. It also connects in the British Isles where the root of so much of this stuff comes from. Australia has a connection to England, Ireland, and Scotland. I would be more surprised if we were going off to play football stadiums in Brazil.

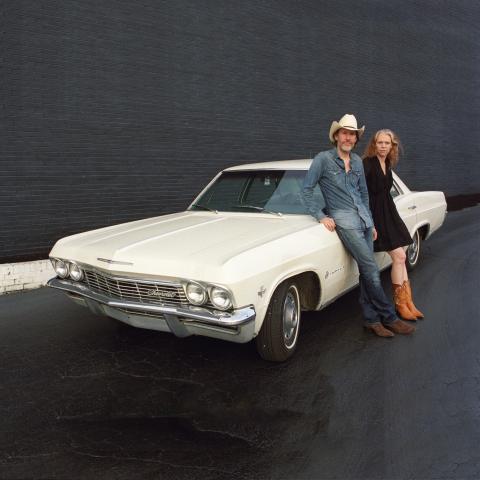

Berklee alumni David Rawlings and Gillian Welch '92

Henry Diltz