Gratitude

This year I spent Thanksgiving Day at Auschwitz, Poland, at the site of the Nazi concentration camps while working on a BBC film produced to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. I ate my meal that day in a catering truck with some musicians and BBC tech people. I sat at a table with classical composer Osvaldo Golijov and his son Yoni. It was only when clarinettist David Krakauer sat down and said, "Happy Thanksgiving" that I realized we were sharing a Thanksgiving that would leave a deep impression on us all.

The intent of the BBC film is to reflect on the events at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camps and their wider significance through music. Performances of works by Bach, Mozart, Messiaen, Gorecki, Reich, Golijov, and others were filmed in the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex.

Music had been part of the daily routine for the prisoners at Auschwitz. The musicians were ordered to play marches at the camp gates so that the labor gangs could march in time. They were also expected to perform for the SS and Nazi officers at any time of the day or night. I have read books written by Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, Szymon Laks, and Fania Fenelon, survivors who were part of the concentration camp orchestras. It was quite moving to play there.

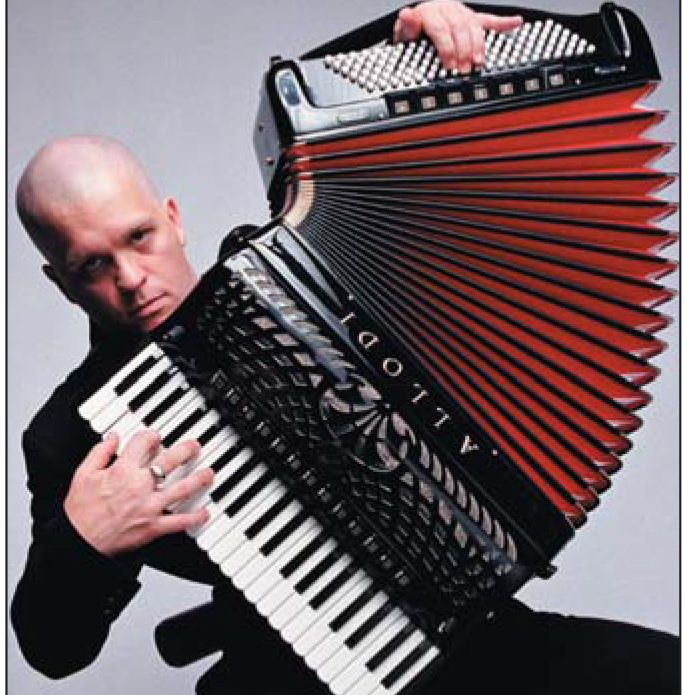

We performed Golijov's Tekyah in a small forest at the edge of the former concentration camp behind the numerous empty barracks that Thanksgiving Day. A freshly fallen snow had left the ground and trees white. When the breeze blew, snow fell lightly from the branches. It was quiet. Golijov scored his piece for brass, clarinet (played by David Krakauer), accordion (which I played), and 12 shofars (ram's horn trumpets used since the days of ancient Israel for worship).

I have learned so much by working with Golijov and the unique musicians he brings together. One of the most important things is the sincere gratitude he expresses for every musician with whom he works. He writes music with both the musician and the instrument in mind because he believes that the two are connected.

Spending Thanksgiving at Auschwitz stirred feelings of gratitude for the circumstances of my life and for music. We all know that life is not always easy; some suffering seems built into the human experience. To always maintain feelings of gratitude is probably life's greatest challenge. As an artist, loving what you do and struggling to be heard and to earn a living can draw you out of that mindset.

I am learning to appreciate what I have while still striving to do better. I learn more and more to trust the process and to be grateful for each experience. Of course, it is easy for me to have gratitude when I get a well-paying, high-profile gig with accommodations in a nice hotel. The challenge is to be grateful for the dinner gig where I am playing my heart out and no one seems to be listening or when I am schlepping home with all of my gear on the last train with 25 bucks in my pocket.

Although I was a piano performance and music synthesis major at Berklee, I also played accordion quite a bit. Within a few weeks of arriving in Boston, I began receiving calls to play on numerous projects by the many international students at the College. I learned very quickly about the the accordion's vast reach in many diverse musical cultures around the world.

This experience inspired me to investigate the opportunities that Berklee offered to learn about world music. I was led to Jamey Haddad and Mikael Ringquist in the Percussion Department. In their classes, they create a comfortable environment where the students have opportunities to listen, share, make music, and learn. I took every class with Jamey and Mikael that a nonpercussionist could take. Jamey also encouraged me to play accordion in his ensemble where we investigated many different styles of music. This prompted me to join the World Music organization in Boston, which is where I first heard the Romanian Gypsy band Taraf de Haidouks.

A couple of months before I graduated, I had a life-changing, five-hour accordion lesson with Ionita Manole, a member of Taraf. Soon I began focusing most of my energy on practicing the accordion. During this time, I received a call from Berklee Professor Jan Moorhead who told me that a local composer named Osvaldo Golijov was looking for someone to help with his computer music studio. I felt that the gig wasn't for me, but after being persuaded by Jan that this could be "a foot in the door," I agreed to contact Golijov's assistant and tell him a little about my experience with technology. But because I wasn't really interested in an engineering position, I spoke more about how much I'd been practicing accordion every day after being inspired by a member of Taraf de Haidouks.

He replied immediately. "Well, this is a small world; Osvaldo is very close with Taraf." When Golijov and I met, we hit it off, and soon we were working together. I helped him with technical issues in his studio and kept him up-to-date on my accordion practice and some new techniques I was developing. Ultimately, Golijov asked me to play accordion on a large work he was composing, La Pasión Según San Marcos. The piece would become one of his most notable works thus far. I soon found that many other Berklee alumni and teachers would be involved with the project.

Mikael Ringquist was an integral part of La Pasión, as Bata drumming and tradition were featured. Other Berklee alumni on the project included vocalist Luciana Souza '95, guitarist Aquiles Baez '96, multi-instrumentalist Gonzalo Grau '98, and percussionists Ruskin Vaughn '96 and Damian Padro '04. Rehearsing and performing the work inspired in me a deep gratitude for the music and musicians and for Golijov's vision.

After the premiere of La Pasión, I moved to London. My wife, who is British, had enrolled in university in Britain. After a while, Golijov contacted me regarding a new piece he was working on titled Ayre. It was to be premiered at Carnegie Hall and would feature the soprano Dawn Upshaw. After a few performances the piece would be recorded. Glancing through an e-mail related to the recording, I noticed Jamey Haddad was going to play on the sessions too.

Haddad and Ringquist, who profoundly affected my development as a musician, had crossed my path again. I reflected on this and decided that they are not only master teachers of rhythm in a musical sense but also messengers of rhythm and continuity in my life.

It was when I returned to London after the Ayre recording that I was asked to participate in the BBC film that placed me along with Golijov and others at Auschwitz on Thanksgiving Day. While we were there, Golijov told me, "Every piece is a journey along a certain emotional territory, and there are people that are better suited than others to take certain journeys." For me, an important key to taking these journeys is to try and consistently put myself on a path where I have gratitude for each note that I play. It helps to follow that which resonates within you the most. The greater the resonance within us as musicians and human beings, the greater our potential will be to touch the lives of others in meaningful and profound ways.

Participating in the memorial film at Auschwitz has awakened a deeper sense of gratitude within me. I'm thankful to have been a small part of something that may have the potential to offer some reflection and healing through music for a tragic episode in our recent history. I've learned that we should always be grateful in our hearts for those musicians, friends, and family with whom we share the joy of music and other meaningful experiences in our lives.