Remembering a Guitar Giant

John Abercrombie

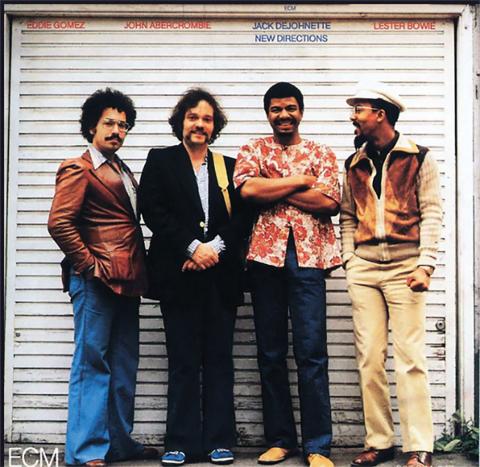

From the left: Eddie Gomez, John Abercrombie, Jack DeJohnette, and Lester Bowie on the cover of the 1978 ECM album New Directions.

Abercrombie plays the Albion model guitar built for him by luthier Ric McCurdie.

August 22, 2018, marked one year since the passing of jazz guitar great John Abercrombie (1944–2017). For many Berklee musicians, his career is a model worth emulating. While his prodigious output and substantial accomplishments didn’t bring him the larger audiences or record sales that John Coltrane, Miles Davis, or Pat Metheny achieved, Abercrombie nonetheless built a legacy of contributions to jazz through his playing style, compositions, live performances, and appearances on more than 50 recordings.

Guitar professor Mick Goodrick ’67 remembers meeting Abercrombie in 1963, when they were both Berklee students. Goodrick says that, at that time, the number of guitarists enrolled was barely two dozen. “John got here the year before I did,” Goodrick says. “He was the first real friend I made at Berklee. We were both studying with Jack Petersen, the guitar instructor here at the time.” The two remained fast friends for the remainder of Abercombie’s life. “I used to call him every year on his birthday,” Goodrick recalls. “He had the same birthday as Beethoven: December 16.”

Abercrombie grew up in Greenwich, CT, and is the son of Scottish immigrants. His home wasn’t musical, and he discovered the guitar on his own as a teenager after hearing the early rock ’n’ roll of Chuck Berry and others. He stated in numerous interviews that the guitar—specifically electric guitar—had an instant effect on him.

In the 2017 documentary on his life, Open Land by Arno Oehri and Oliver Primus, Abercrombie shares his progression from being a fan of rock ’n’ roll to discovering jazz guitar after hearing a recording of Barney Kessel to getting deeper into jazz through the Dave Brubeck Quartet and others. When his guitar teacher played him a Miles Davis album, Abercrombie says “light bulbs went off.” He later became entranced by recordings by Jim Hall, Wes Montgomery, and many other jazz instrumentalists.

When Abercrombie wanted more musical knowledge, Berklee was the only institution offering formal jazz studies. He was pleasantly surprised when his parents supported his choice. Abercrombie studied at Berklee for four years and then stayed in Boston for another four. He frequently worked at Paul’s Mall, one of a pair of nightclubs at 733 Boylston Street that included the famous Jazz Workshop. Abercrombie backed various artists at Paul’s Mall and on his breaks would listen to artists in the Jazz Workshop. (Both clubs closed in 1978.) He got to hear sets by Miles Davis, Bill Evans, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, and others.

In Open Land, he speaks of meeting many top musicians during that period. He recalls a humorous encounter in the alley behind the club where he and his bandmates were smoking pot. Monk, who was playing at the Jazz Workshop that night, came upon them in the alley and stood by watching. Abercrombie gestured, offering Monk a puff. He says that the pianist accepted wordlessly and then proceeded to smoke the rest of the joint himself. He smiled, handed the stub back to Abercrombie, and returned to the bandstand.

The first recording the guitarist played on was the record Nasty! with organist Johnny Hammond Smith, drummer Grady Tate, and saxophonist Houston Person in 1968. George Benson was slated to be the guitarist on the date, but when he couldn’t make it, Smith asked Abercrombie to fill in. “It was funny because I was a young, white guitarist with no reputation,” Abercrombie said, “and I was the sub for George Benson! Here I was in a recording studio with real jazz musicians making my first jazz recording at 21. I was scared, but trying not to show it.” During a playback, Tate, a veteran jazz drummer, turned to Abercrombie and told him he sounded good. That was just the boost he needed to relax and play confidently on the rest of the tracks.

After Abercrombie left Boston for New York City, he became a founding member of the early jazz-rock fusion band Dreams, with Michael and Randy Brecker and Billy Cobham. The band is not remembered as much for their songs as for the above-mentioned members who later found success with other groups as studio musicians and solo artists. Abercrombie soon received multiple requests for recording sessions with such artists as Gil Evans, Gato Barbieri, Barry Miles, and more.

By this time, the fusion movement was in full swing. Cobham had made a name with John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra, and released his first solo album, Spectrum, in 1973. Guitarists Tommy Bolin and John Tropea played on the record, but Abercrombie played the live dates. On Cobham’s second album, Crosswinds, Abercrombie was a featured soloist on the funk jam “Crosswind.” It was a great showcase of his formidable fusion chops, and a wider audience took note of him.

But Abercrombie was moving toward the jazz genre, and a key figure in his transition was drummer Jack DeJohnette. “Meeting him was one of the turning points in my life,” Abercrombie said in a 2010 Guitar Player magazine interview. “We played everything. We played the space-rock that he had invented with Miles, along with swing and standards. In addition to playing with a great drummer, I was playing music that I really wanted to play.”

Abercrombie later met Manfred Eicher, the founder and producer for the German Euro-jazz label ECM. Eicher invited him to record for the label. It was the impetus for Abercrombie to begin composing his own material. In 1974, Abercrombie came to the studio with keyboardist Jan Hammer (formerly of Mahavishnu Orchestra) and DeJohnette. The resulting album, Timeless, was a watershed LP with music that covered a range of influences. Hammer’s “Red and Orange” and Abercrombie’s “Ralph’s Piano Waltz” offer a take on the jazz organ trio sound with a dose of fusion energy. “Ralph’s Piano Waltz” was a piece Abercrombie played throughout his career and even revised and titled “Another Ralph’s” for his 2013 ECM release 39 Steps. Other tracks on Timeless, such as “Love Song” and the title track, were more introspective with a quiet intensity.

Abercrombie enjoyed a long affiliation with the ECM label, from 1974 to his final album, Up and Coming, recorded in 2016. “What tied me in with Manfred Eicher and a lot of the other musicians that worked for ECM,” Abercrombie explained, “was that we liked a certain aesthetic or feeling in music which has to do with being a little melancholy, a little sad, not so in your face, and a little mysterious.” All of those qualities can be heard on Timeless.

“That album was probably the most successful recording I’ve ever done,” he shared in the documentary. “The record sold well and put me out there in the world as a leader, not just a sideman. I had an identity. I got to be a leader and go around the world playing my own music. I am really indebted to ECM for doing this project. It was my ‘hit.’”

Abercrombie had fruitful musical relationships with other artists on the ECM roster, including Jan Garbarek, John Surman, Kenny Wheeler, Enrico Rava, and many more. Fellow guitarist Ralph Towner was another, and as a duo, Towner and Abercrombie appeared in concert playing an array of instruments, from Towner’s classical and 12-string guitars and piano to Abercrombie’s six-string acoustic and electric guitars and electric mandolin. Their attractive impressionistic soundscapes were captured on their Sargasso Sea and Five Years Later albums released in 1976 and 1982, respectively.

Abercrombie’s other recording and touring projects included critically hailed bands with DeJohnette, such as Gateway Trio (Abercrombie, DeJohnette, and bassist Dave Holland) and New Directions (Abercrombie, DeJohnette, bassist Eddie Gomez and trumpeter Lester Bowie). “The Gateway Trio with John and Dave Holland was a very special group,” DeJohnette says. “We made some great records and did a lot of concerts. The last project I did with John was a reunion concert with Gateway Trio in Chicago a few years before he passed. It was really a joy playing with them.”

Additionally, Abercrombie formed a notable quartet featuring pianist Richie Beirach, bassist George Mraz ’70, and drummer Peter Donald. Throughout his career, Abercrombie worked with many more band configurations and collaborators than can be adequately chronicled here.

One of his musical compadres, saxophonist Joe Lovano, offered a few words of tribute for this article. “Some of the most beautiful, poetic moments of music in my lifetime came from shaping melodies with John,” Lovano says. “His free-flowing approach and constant development of ideas were personal and expressive within whatever music we were playing. He had a way of being in the rhythm section and the front line simultaneously, which would fuel everyone’s ideas in the ensemble. John set the pace on the scene since his first emergence, and his contribution will forever be ‘timeless.’ He was also one of the kindest, funniest, and loving people you could know.”

Many others have praised Abercrombie for his lyrical improvisations. After years of playing with a pick, sometime during the 1990s he began articulating notes and chords with his right-hand thumb only. He sought a refinement of his sound and feel on the instrument. In a 2004 JazzTimes article, David R. Adler observed that Abercrombie had “sacrificed some velocity and fluidity for increased body, and his electric sound, once distant, harder to follow, now has more texture and substance.” Abercrombie reflected on his evolution as well, “I think my time improved. I feel more connected to the rhythm of what I play. I’m able to be more melodic.”

Abercrombie passed away from heart failure in 2017, surrounded by those closest to him, including Lisa, his devoted wife of three decades. Many have offered props to Abercrombie, including luthier Ric McCurdy, who built four guitars for him. “I hear all the great guitar players here in New York, but you could tell it was John in a few notes,” McCurdy says. “He had a true identity; which has to be the hardest thing to develop in jazz.”

Many who knew him speak of his personal warmth and sense of humor as well as his musical talent. “John left a great legacy in his music,” DeJohnette says. “But he was also one of the most caring and loving people that I’ve known. I miss him dearly.”

It was especially meaningful to hear accolades from one nonmusician. In Open Land, Abercrombie said of his father, “[He] wound up being proud of what I was doing, even though he didn’t understand what I wanted to do in jazz—especially when I became well-known and was recording and appearing in magazines. He actually told me he liked a couple of records I did.” When pressed for the specific albums he liked, the senior Abercrombie mentioned John’s first recording with organist Johnny Hammond Smith. “He said he liked it because it ‘really sounded like jazz,’” John shared. This seemed an unusual choice from someone who didn’t know much about music, and after the many albums the guitarist had made by that point. Abercrombie’s demeanor in the documentary appears to reveal that it was reassuring to receive validation from his father.

In a quote from the guitarist himself on the ECM website, he said, “I’d like people to perceive me as having a direct connection to the history of jazz guitar, while expanding some musical boundaries.” Mission accomplished, John. Rest in peace.