Other Paths

Ample evidence suggests that the skills developed in the quest for the mastery of music have application to other endeavors. The creativity, problem-solving, decision-making, and analytical abilities critical to writing and playing music serve musicians well in nonmusical pursuits. Peiter “Mudge” Zatko ’92, Eric “T” Fleisher ’82, Arthur Phillips ’93, and Chris Waterman ’76 are all examples of this talent crossover. These Berklee alumni are well-trained musicians who are also bright lights in careers that lie outside the musical sphere.

Peiter Zatko (second from the right) advised the Clinton administration on information security.

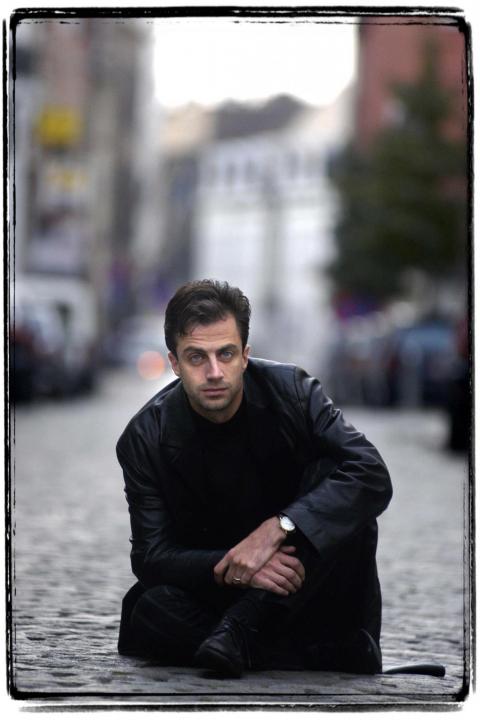

Best-selling novelist Arthur Phillips ’93

Horticulture expert Eric “T” Fleisher ’82

Information security architect Peter Zatko '92

Anthropologist and UCLA Dean Chris Waterman ’76

Job Security

Peiter “Mudge” Zatko is regarded as one of the top architects in the information security community. As we talk in his office at BBN Technologies in Cambridge, Massachusetts, he says that during his childhood his heroes were iconoclasts Frank Zappa and Abbie Hoffman. On the surface, they seem to be odd role models for a man who has testified before the U.S. Congress and advised then-President Bill Clinton on matters of information infrastructure security. Zatko’s interests in music and computers flowered early and led him naturally to this point.

Zatko began to study violin and guitar seriously as a child. When he was in elementary school, his family got an Apple II computer, and the inquisitive Zatko began to explore computer security. “I wanted to figure how to break the copy protection scheme so I could make a backup copy of my games and software,” he says. “I’d spend $100 for a game or a program on a 5 1/4" floppy disk, and I wanted a backup. I started figuring out how to reverse-engineer things to make the computer do what I wanted it to do, not what the makers wanted.” Later Zatko got a modem and began surfing the loose confederation of bulletin board systems and the ARPANET, which preceded the Internet.

When it came time for college, Zatko opted to major in music rather than computer science. “I wanted to learn about music just for myself,” he says. “I liked playing progressive rock but knew there wasn’t a big market for it. I wanted to formalize my understanding of music and get a college degree. I figured I could change the world in other ways,” he says chuckling.

Zatko graduated at the top of his class at Berklee majoring in professional music. His final project was a five-minute 3-D movie that he created and scored on an IBM 386 computer. “There wasn’t software available to do what I wanted, so I made each frame individually,” he says. “I created a 3-D visual of a city and then did a fly-through, tracking my own music under the visuals. It took me my entire last semester to complete it.”

After college, Zatko played clubs with his progressive-rock band Raymaker before being hired by BBN Technologies to start the company’s corporate security group. After hours, a coterie of Zatko’s tech-oriented friends adopted aliases and set up a hacker group known as L0pht. Members pooled their gear in a rented space and created their own networks. Eventually they assembled about 200 computers, a parallel-processing supercomputer, and antenna masts on the roof for signals intelligence. “We wanted to learn how networks broke down without breaking the law by experimenting on other people’s networks,” Zatko says. “People thought we crossed the line when we published articles telling where the weaknesses were in networks and computer systems.”

Zatko wrote a now-legendary program called L0phtCrack that broke Microsoft Windows passwords and was a pioneer in the computer underground in creating attacks known as buffer overflows. The L0pht group was the first to post Web articles on the vulnerabilities of Microsoft products. “Microsoft said L0phtCrack wouldn’t work on their products, but one of our members showed how it worked on Windows,” he says. “We made them look bad and they hated us for it, but this was one of the main reasons that Microsoft started a security team. Intel also has a team to handle feedback from people who point out problems that put users at risk. We kind of changed the environment.”

Zatko and the software companies he founded gained notoriety through write-ups in major newspapers, and sales of Zatko’s L0phtCrack and AntiSniff software reached a half million dollars a year. “We made the front page of the Washington Post as a hacker collective in Boston that was turning out a lot of stuff,” he says. “We were perceived as Robin Hoods of sorts. Although our information could be used by some for malfeasance, I thought it was important that people know about the weaknesses in their systems to protect themselves.”

During the late 1990s, representatives from the federal government sought Zatko and L0pht’s expertise to determine if weak security in government computers placed the public at risk. Using their aliases, L0pht members testified before the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs and created a stir when Zatko stated that he could take the entire Internet down in 30 minutes and keep it down for some time. Zatko later assisted the Clinton administration as an adviser to the National Security Council and the Senate Democratic Policy Committee.

“It wasn’t a case of us being evil hackers crossing over to work for ‘the man,’” claims Zatko. “Before 9/11, I did lot of work with the government, and after the attacks I did even more. I took a leave of absence from my company and did pro bono work for the government. I was a citizen with capabilities the country needed, and I felt it was my responsibility to help.”

Zatko is currently the technical director of National Intelligence Research and Applications for BBN. He works with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the central research and development organization for the Department of Defense, as well as other DOD entities and helps to create, develop, and execute projects that receive funding.

Zatko also still actively plays the guitar in bands. He sees links between the processes for problem solving in music and science. “For those who have had experience with music growing up, it becomes easy to take the thought process they have internalized and take it to the hard sciences or mix them together.”

The Godfather of Soil

Like Zatko, Eric “T” Fleisher is also a guitarist and a celebrated expert in a nonmusical field. Since 1989, Fleisher has been the director of horticulture at Battery Park City Parks Conservancy (BPCPC) in lower Manhattan. The 36-acre park system is acclaimed as the only public space in New York that takes a completely organic approach to managing its landscape and has become a model for facilities elsewhere. Through his work at BPCPC, Fleisher has become widely known as an expert on balanced soil ecology, nontoxic pest control, composting, and water conservation. During this academic year, Fleisher is in residence as a Loeb Fellow at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. In 2006 he received the Silver Honorary Medal from the Massachusetts Horticulture Society for his environmentally sound gardening methods. He’s also a consultant for the creation of Boston’s Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway Conservancy.

“I’ve always liked horticulture but never thought it would be my profession,” says Fleisher. “A great-uncle of mine was in the nursery trade in Connecticut. I spent summers around him as a kid and developed an interest in horticulture and environmental issues.”

Fleisher had gotten into music growing up and in 1978 first learned about Berklee at a jazz club in Hartford, Connecticut. “I went there to hear Pat Metheny’s group,” he says. “There were very few people there, and I spoke with Pat afterward. He told me the place to go to learn about jazz was Berklee.”

Fleisher took Metheny’s advice and enrolled, earning his Berklee degree in 1982. He then moved to New York where he did session work, composed, and played all manner of gigs. But he soon discovered that the music business didn’t match his expectations. “I wasn’t willing to do anything so that I could make my living in music,” he says, “but when you’re starting a career, that’s what you have to do. Fortunately I had this other love. When I found the environmental niche within the horticulture field, it was like a calling to me.”

When Fleisher took the reins at BPCPC in 1989, the notion of maintaining a high-profile park organically was unprecedented. Initially, many were skeptical, but the park’s executive director, Tessa Huxley, supported Fleisher’s organic approach. He had to justify his methods scientifically, but ultimately Fleisher and crew showed that an urban park could be managed organically. The fact that no harsh chemicals are used for fertilization or pest control is comforting to parents whose children play on the grass there.

“You don’t have to keep throwing fertilizer on your landscape,” Fleisher says. “In fact when you do, you increase salt levels and kill off bacterial and fungal populations and ruin the natural balance. It’s like getting your landscape hooked on junk food. In a healthy, diverse soil system, the plants release sugars and starches that fungal organisms feed on. The plants in turn need zinc, magnesium, and other micronutrients. The fungi help the plant to absorb and metabolize the micronutrients. Once this cycle is operating, the fungal organisms protect the roots from root-feeding nematodes [worms] and pathogens. When you use a high-nitrogen fertilizer or a fungicide to kill spots on your lawn, you also kill the fungi that protect the plant roots, leaving them vulnerable to infection from pathogens that are always in the soil.”

The BPCPC collects green plant waste as well as coffee grounds from Starbucks and preconsumer waste from grocery stores to make a compost that fosters a healthy soil. “We mimic what happens in nature in making a compost tea containing the beneficial bacteria, protozoans, and nematodes,” Fleisher says. “Applying the tea enhances these populations.”

Fleisher’s success at BPCPC has been the subject of several New York Times stories and has garnered attention in other quarters. He wants to document his findings so that others can follow his lead. During his year at Harvard, Fleisher hopes to develop the basis of a book. “For 18 years, I haven’t had the time to step back and do that,” he says. “I want to make this information available to people.”

Fleisher still plays blues, r&b, and jazz with the Threads, progressive rock with Cybergarden, and jazz duo gigs. “I still have a real passion for music. It was a privilege to spend four years studying jazz. The study of music is a lifelong commitment, and it’s much the same with horticulture.”

Writing Fiction in Real Life

Sitting in a sunny Brooklyn dog park a few blocks from his workspace, Arthur Phillips ’93 details the route that led him from Harvard to Budapest to Berklee to national best-seller lists as his beagle puppy Hamish cavorts with other canines. He tells me that after graduating from Harvard in 1990 with a degree in history, it wasn’t yet apparent to him what his life’s work would involve. That summer he went to Budapest, Hungary, shortly after that country and others in Eastern Europe freed themselves from communist rule. Some important life experiences came from his two-year Hungarian sojourn. One outcome of the trip was a desire to seriously study music; another was the accrual of a variety of impressions that formed the backdrop for his first novel, Prague.

“When I was in Budapest, I fell in love with the saxophone and started practicing eight hours a day,” Phillips says. “I came back and enrolled at Berklee. There is a character in the novel Prague who is a jazz musician—that would be me.”

Phillips studied for four semesters at Berklee and had Andy McGhee as his tenor saxophone instructor. After leaving the college, Phillips dove headlong into the life of the professional musician. He led jazz bands in the Boston area, held a steady gig at the Copley Plaza Bar for two summers, and met his future wife at Ryles.

“I was able to make a living playing music for four years,” Phillips says. “I was getting plenty of gigs, but doing that wasn’t making me happy. I didn’t know how to get from the technical information I’d learned at Berklee to finding something new and exciting.” Ultimately, Phillips followed other pursuits, including freelance jobs writing speeches, PR copy, and press releases before he began writing fiction.

“I discovered that writing fiction was something I liked to do more than play music,” he says. “I began writing Prague in 1997 and worked on it for four years. After I finished it, I wanted to sell it. The experience I’d had selling myself as a freelance musician probably helped a little, but publishing is a very different industry. There’s no life without an agent in this field; you practically need an agent to get an agent. They’re hard to find and pin down, but I got lucky.”

In 2002, Random House published Prague (which is actually set in Budapest). It was a major success and critics immediately embraced it. Prague was named a New York Times Notable Book, and Phillips received The Los Angeles Times/Art Seidenbaum Award for best first novel.

“Prague caught on right away,” he says. “That particular year, there were four or five novels set in Central and Eastern Europe, and people talked about them as a group. I don’t know why mine caught on. Once it did, it changed my life and I became a full-time novelist.”

Phillips’s second and third books are historical novels. The Egyptologist, a bestseller set in the 1920s, was included on many critics’ Best of 2004 lists. Phillips’s third book, Angelica, set in 1880s London, gained instant acclaim when it was published earlier this year. A critic from the Washington Post said, “Phillips’s third book cements this young novelist’s reputation as one of the best writers in America.”

Music and/or musicians are a colorful thread woven into each of Phillips’s books. In The Egyptologist, the main character is a gramophone lover with a collection of wax cylinders. “There’s also mention of jazz bands playing at places in Boston and in Egypt,” says Phillips. “My fourth book will be a music novel set in contemporary Brooklyn. The central character is an older man who is obsessed with music but doesn’t play. He’s a guy in love with his iPod who falls for a woman singing in a bar and pursues her. I may write a historical look back to the 1950s and Billie Holiday.”

Phillips has a strong work ethic that enables him to complete a book every two years and still enjoy life with his wife and two sons. “I had to get rid of the notion that a writer had to be someone who could walk away from whatever was going on to write something down,” he says. “That’s a romantic artist story that gets made into movies: the artistic sociopath who dedicates everything to his art and can’t have a relationship, a job, or a family because he needs to be there when inspiration strikes. You don’t need to live in a hovel or alienate everyone you know, be stoned, drunk, or suffering any more than anyone else. I haven’t done a real study of it, but I suspect that most great art came from people who took their work very seriously and tried to lead a full life around it. There is plenty of romance in art no matter how you do it. I feel fortunate that this is the job I get to do every day.”

The Long View

Chris Waterman ’76, dean of the School of the Arts and Architecture at UCLA, jokes that a genetic predisposition in his family must have drawn three generations to the bass. His father was a bassist, Waterman came to Berklee aspiring to become a career bassist, and his son has also taken up the bass. But there is more to the story that led Waterman to his current position as the dean overseeing UCLA’s Architecture and Urban Design, Art, Design/Media Arts, Ethnomusicology, Music, and World Arts and Cultures departments; as well as three museums, and UCLA’s Center for Intercultural Performance; Experiential Technologies Center; and the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, and more.

Growing up, Waterman was exposed to a panoramic view of the arts through his parents, who were both anthropologists. His father was an ethnomusicologist specializing in the African roots of the music of the Americas. Having played gigs from the age of 14, Waterman came to Berklee to study bass and composition. After graduating, he went on the road for a year.

“As I toured the Southeast, I started meeting musicians in their sixties who had no health insurance,” Waterman says. “So I decided to augment my playing with something else. My parents didn’t raise me to become an anthropologist, but something about the worldview of an anthropologist makes you want to learn something about other people and what motivates their behavior. Human beings are at the center of music. Anthropology seemed like a good way to understand music.”

In 1977, Waterman enrolled at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana, where he received his Ph.D. in anthropology with a focus on music’s relationship to religion and social life in a number of different cultures. Fulbright scholarships and social science research grants enabled him to spend the summer of 1979 in Nigeria and return to live there between 1980 and 1982. “Later, when I looked at religion in Brazil and Cuba, I could see ties to Nigeria,” he says. “There was something about the religion, culture, and food that carried through the tragedy of slavery and gave them a source of strength.” In 1990, Waterman distilled his observations in the book Juju: A Social History and Ethnography of an African Popular Music.

Waterman’s first faculty appointment at the University of Washington placed him in 700-student lecture classes teaching about American pop and world pop music. “It was a young, diverse, nonmusician audience, and I wanted to get them to listen to the music and understand the creativity involved as well as the politics, technology, language, and culture behind it.” From that experience came the textbook American Popular Music: From Minstrelsy to MTV, coauthored with Larry Starr.

Waterman ultimately spent 11 years at the university and became the chair of African studies before accepting a faculty position at UCLA. He helped to create a new Ph.D. program in culture and performance in UCLA’s World Arts and Cultures Department. “It was an attempt to look in a cross-cultural fashion at creativity and the arts in the broadest sense and see how music relates to dance and movement and culture in general,” he says. Chairing the department for five years, Waterman interacted with faculty members specializing in globalization and migration, Native American cultures, Cuban Santeria, Haitian popular art, as well as choreography and dance.

Five years ago, Waterman became dean of UCLA’s School of the Arts and Architecture and has overseen the exploration of links between architecture and film and architecture and sound and music. One project involved a digital recreation of a church of medieval Spain. “You walk in wearing 3-D goggles and enter a space that is a digitally recreated environment,” Waterman says. “It has been acoustically modeled so you can hear period music replicating the experience of a pilgrim in Europe in the fourteenth century. I love the idea of architects trying to recreate the past. Sound is very important in architecture.

“UCLA is a tier-one research university with the potential to connect the arts to other fields. I enjoy the potential for interdisciplinary research and creativity here. The arts and sciences are kept separate at many American universities. As an anthropologist who is used to looking at connections and context, this is a stimulating place.”

Though most of his life is centered on academe, Waterman stays in touch with his own roots. Nights and weekends he plays gigs and still loads his own equipment out of freight elevators and into hotel ballrooms. “It keeps me in touch,” he says. “When I went to Berklee, I was intent on making a living as a bassist, but at some point I got pulled into the larger questions. For me, the combination of anthropology and music is a great one.”