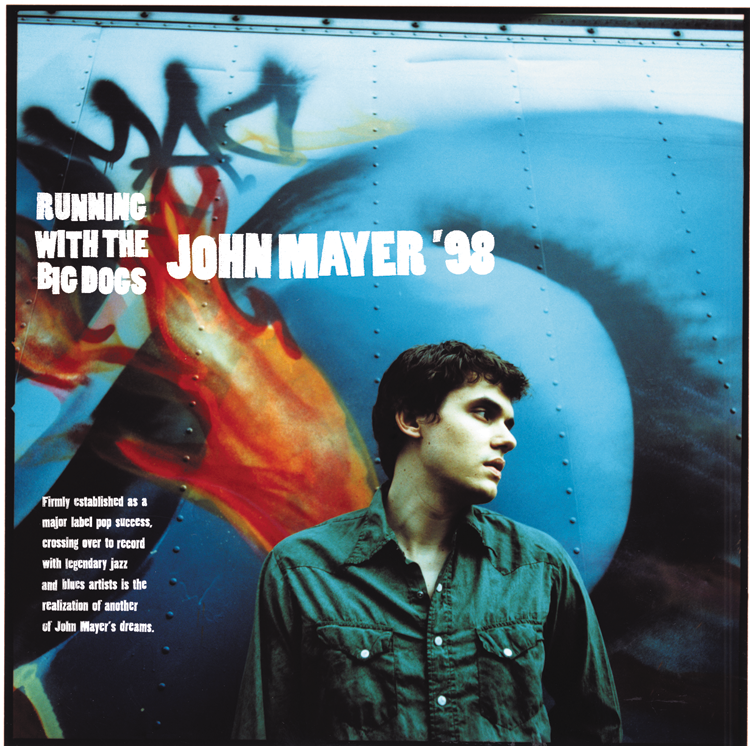

Running with the Big Dogs John Mayer ’98

Inside his dressing room backstage on the set of the Tonight Show with Jay Leno, John Mayer is cool as can be as we chat before his upcoming cameo appearance with John Scofield’s band. Mayer sang and played guitar on “Don’t Need No Doctor” from Sco’s latest disc, That’s What I Say: John Scofield Plays the Music of Ray Charles. Scofield, Mayer, drummer Steve Jordan, bassist Willie Weeks, and rhythm guitarist Avi Bortnick will perform the live version tonight before millions of NBC viewers. It’s a win-win situation for Scofield and Mayer. Sco plays before a huge TV audience with a pop star, and Mayer reveals another side of his artistry playing alongside a revered jazzman.

John Mayer ’98

Living out youthful musical dreams of being welcomed onstage and into the studio by musical giants such as Scofield, Herbie Hancock, Eric Clapton, Buddy Guy, and scores of others is only a portion of the spoils of Mayer’s success. Becoming one of Columbia Records’ top artists, a huge box-office draw, a radio hit maker, and a three-time Grammy winner who has sold nearly seven million records (with an eight-figure income in 2004) are other attractive aspects.

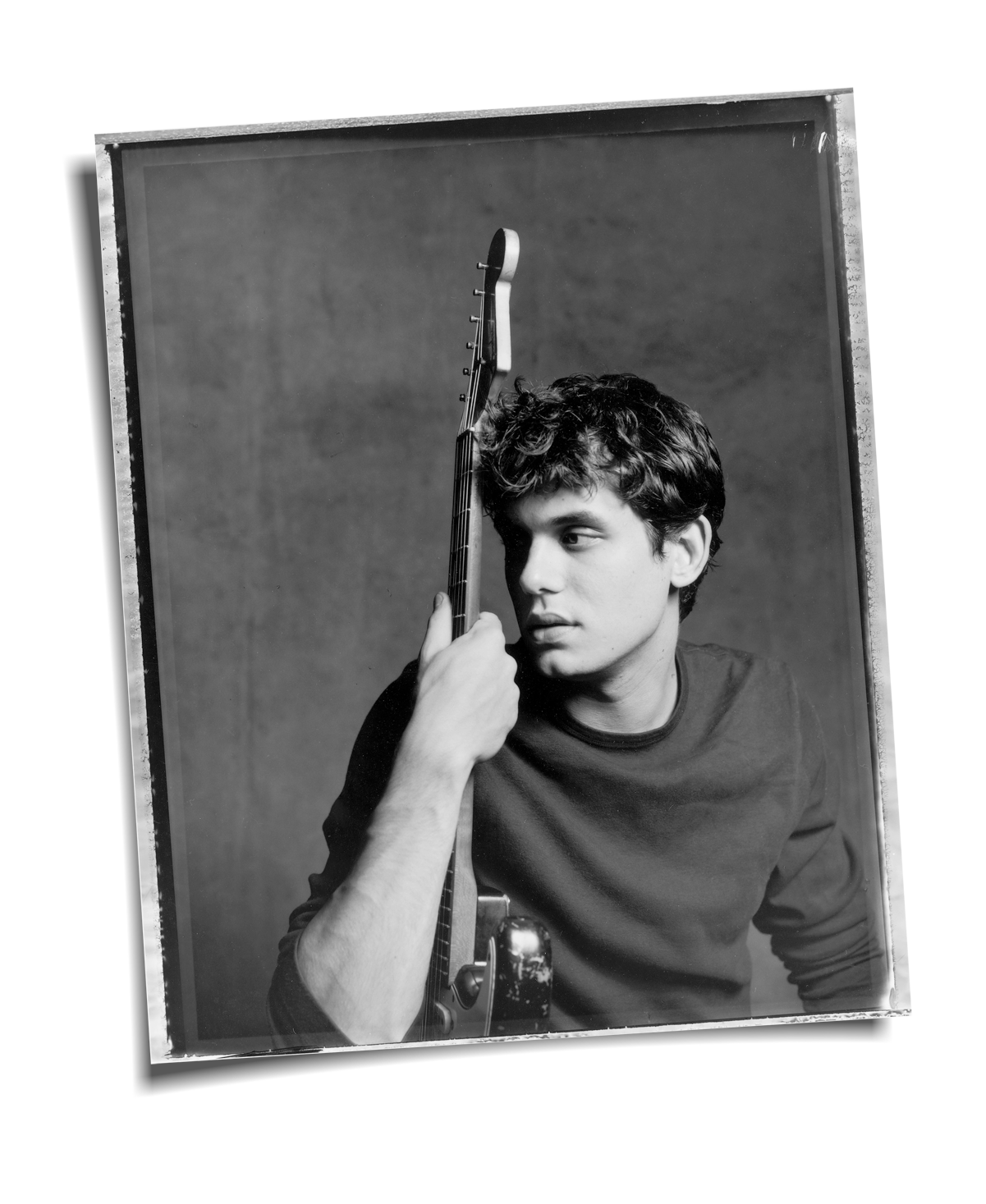

The 28-year-old Mayer’s first serious musical interest was playing the blues in 1990, and Stevie Ray Vaughan’s approach became his template. Mayer came to Berklee in 1997 hoping to sharpen his guitar skills but he made a course correction after his first semester. Mayer realized that his gift for songwriting was the club key to where he wanted to go. Before the end of his second semester, in 1998, he left Berklee to find his path into the business. After knocking around the clubs in Atlanta for a time, Mayer had created a buzz and amassed enough good songs for his indie release Inside Wants Out. Mayer’s abilities as a triple-threat artist with a thumbprint vocal sound, multifaceted guitar chops, and stature as a songwriter with something to say grabbed the attention of several labels.

By 2001, Mayer’s Aware/Columbia Records debut Room for Squares was scaling the charts powered by the songs “No Such Thing” (cowritten with Clay Cook ’98) and the Grammy winner “Your Body Is a Wonderland.” Mayer’s second Columbia outing Heavier Things entered the charts at number one, buoyed by the single “Daughters.” That song, which netted Mayer his second and third Grammys in February 2005, reveals his depth as a lyricist and performer. Its gentle, even romantically stated message about the generational effects of bad parenting accompanied simply by guitars and a piano (no drums) seemed an unlikely hit in today’s musical climate. Its embrace by listeners and the music business establishment alike was an indication that Mayer is no flash in the pan; he’ll be around for a while. He may yet become recognized as one of his generation’s spokesmen, just as Paul Simon, Joni Mitchell, James Taylor, Sting, Bruce Springsteen, or Bob Dylan have been for theirs.

Producer, songwriter, and guitarist Clay Cook '98

One on one, Mayer comes across as confident, very bright, lighthearted, and yet extremely serious about what he’s doing. He was firmly in the moment, thinking about his next recording and his new all-star trio that will feature bassist Pino Palladino and drummer Steve Jordan and highlight Mayer’s guitar prowess a bit more than previous recordings. The group opened two early October tour dates for the Rolling Stones. Yes, Mayer is running with the big dogs and demonstrating that he has the staying power to remain at the front of the pack.

When did you write your first song?

When I was about 17, I wrote 10 or 12 songs. At the time, I was flip-flopping between being a songwriter and a hard-core guitar player doing jazz and blues that would showcase my guitar playing. When the idea of going to Berklee came up, I had dropped songwriting for the moment. I never thought of going to Berklee to become a great songwriter; I wanted to learn how to be the best guitar player going. I went for the first semester with that in mind. You confront your own identity right away when you go to Berklee. Some people never saw who they were until they got there. Some had been told by their parents and others that they were great, and it took coming out of the Midwest or someplace else for them to hear other kids playing. I learned a lot hearing other kids who were better players than I was.

John Mayer ’98

It was over the Christmas break that year that I took a hard look at myself and decided to figure out where the target was and how close I was to it. That’s when I realized that I was meant to be a songwriter or a mainstream artist. The best thing I could tell anybody at Berklee is to define your expectations. Life is so much easier when you do that.

Otherwise you don’t know when you’ve hit the mark. Going back for the second semester was interesting for me. I knew that I wanted to be a listenable artist. I wanted to be the guy that the best guitar players at Berklee wanted to hear when all the music in their heads was driving them nuts. I wanted them to come to my room and let me play them a song. That was when I figured out that writing songs was my calling.

In a way, I still don’t think of myself as a songwriter. I think about being a guitar player who writes these pieces of guitar music, but then sings because it would sound weird if there wasn’t singing and [who] writes lyrics because it would be weird if you weren’t saying something important. That’s my approach to being a songwriter. I love playing cool guitar stuff and then singing interesting lines over that and singing words that move people.

I can hear the influence of Stevie Ray Vaughan in both your singing and guitar playing, but I’m curious about the roots of your acoustic guitar playing. It doesn’t sound folk-based.

I’m glad that you hear the Stevie Ray influence in my singing. A lot of people thought I was trying to sound like Dave Matthews, but I was really just doing a poor impression of Stevie Ray. Playing acoustic guitar was always a secondary thing for me. I didn’t have an acoustic when I went to Berklee. My parents had to buy me one half way through the year.

The electric guitar isn’t a self-sufficient instrument for me. Maybe it was for Joe Pass; but for me, when I played the acoustic, I didn’t miss other musicians. When I left Berklee and went to Atlanta, I got into the acoustic because I wasn’t about to waste any time not playing while I was looking for a band. I wanted to go up and play onstage and you can do that with an acoustic. From there, things just kept growing. I still don’t feel that I’m very good at it. For some people, the acoustic is their ultimate expression; for me, it is a little too thick and taut. Lately, I’ve been writing songs on acoustic that I really enjoy playing. My dedication now is to the sensation of playing. I write things that feel good to play and sound good.

When I’m recording an acoustic guitar track, trying to express everything in a way that sounds good closeup is work for me. The difference between playing electric and acoustic guitar is like the difference between stage acting and television. Playing acoustic is like stage acting: everything has to be big and pronounced. You have to hit the strings harder to get them to ring. You need more velocity and pressure on the strings. I like the close-up effect of playing electric. It has a very wide dynamic range. You can play quiet notes and then hit the string harder and bend notes with a lot of control. That is why I’ve been looking for opportunities to play the electric more these days.

Didn’t you study guitar with Tomo Fujita when you were at Berklee?

I had gone to Berklee’s summer session and learned a lot from Tomo. I had watched him play and saw how he did his funky right-hand slapping stuff like bass players do. I went home and worked on that and incorporated some of it into my style.

I must say, by the second half of my second semester, I didn’t go to a lot of classes. I wasn’t being rebellious, it was me saying—“Got it, I know what I want to do.” Here’s an analogy for how I felt about my classes. It was like being at a restaurant when you already know what you want to order and the waiter starts telling you what the specials are. I already knew what I wanted.

I would run into my teachers on the street and they’d say, “Haven’t seen you in class lately.” I’d say, “I can’t explain it, but I’m working on something.” I looked at it kind of like graduating early. I had made my discovery. My friends and I were recording in my dorm room. It felt weird to be enrolled at a music school and not be going to class because I was writing music.

There have always been people who come to Berklee and leave early to go after their dream because they feel ready to pursue it.

I still follow the same force that led me to Berklee and then led me to leave there to go to Atlanta. It’s as if my guitar is a surfboard and I’m just paddling. I have to be fair in terms of my success and say that a lot of people leave Berklee early and don’t make it. I have to be careful and recognize how the odds are stacked. The only way I could know what was me and what was circumstance would be to do it all over again. But I can’t. You only break in once. No matter what you do and where you go to school, if you do it with a holistic understanding of yourself, your identity will save you. You might see someone who can play better than you and then you think, but he can’t write a tune like I can.

How did you end up in Atlanta after leaving Berklee?

I made a friend at Berklee, Clay Cook [see the sidebar “Dorm Room Dreams”], who was from Atlanta, and we started writing songs together. We both decided to withdraw from the college at the same time. Our withdrawal slips probably have consecutive numbers. We cowrote “No Such Thing,” he came up with the bridge chords. I never would have thought to put those in there. After a little while down in Atlanta, the partnership ran its course and ended. I was stuck there in Atlanta after having piggy-backed someone else’s life, car, and job. I remember getting to some pretty dismal places money-wise and opportunity-wise. I kind of looked at my guitar and said, “It’s just you and me. I’ll go where you take me.”

What happened next?

I played at the South by Southwest Conference with just a bass player. We played “Wonderland,” “Why Georgia,” “No Such Thing,” “My Stupid Mouth,” and “Back to You.” I think the only songs that went on Room for Squares that I hadn’t written at that point were “3x5,” “City Love,” and “Not Myself.” After that showcase, some cross talk got started between a few labels.

Why do you think your music has connected so well with people?

I really don’t know, and if I guessed I’d probably be wrong. I am trying to still have edges on me but be accessible to people. Most times when you try to be all things to all people, you end up being nothing. I want to reach the exact equilibrium between palatable and evolutionary. It is very difficult. You can hit it for a song or two, but I’m trying to hit it for a whole record. I want people to feel it’s great the first time they hear it and that it will get better the more they listen. I want devices in there that are a little richer than typical pop-music devices.

You’ve arrived at a very comfortable place with mainstream radio on your side, yet it seems that you’ve got the freedom to express whatever you feel.

Why wouldn’t someone want to be in the mainstream? There is a lot of excuse making among musicians for why they can’t be in the mainstream. You have to define your expectations. If you’re unhappy playing at the Middle East, where would you like to play? If the answer is the Fleet Center, do you play the kind of music that would bring in enough people to fill the place? If the answer is no, a lot of musicians will make some statement about how most people are idiots and don’t want to go to the real deal, so they just settle for what’s on the radio. That’s a belief I don’t agree with.

There are some people who love the Miles Davis Jack Johnson box set, but there are probably more people just looking to hear something fun on the way to work. When you can bring those people something with a little substance, it’s great.

How hard is it for you to write a song and get it into the shape you want?

It is incredibly hard; it’s like code cracking. I like to play the music and hum along. I get cues about what to say by what kind of imagery the music brings to my mind. Then I write that imagery. A new song I am writing is called “Stop This Train.” The groove revisits the shuffle feel of “3x5.” If you can make a connection happen between the image and the music, it almost doesn’t matter what you are singing about. People will understand it.

When I hear Sting’s “Wrapped around Your Finger,” I don’t know what all of the lyrics mean. His melodies are so good that the lyrics are just something to sing. Not that Sting doesn’t write important lyrics, but he says, “I will listen hard to your tuition/ You will see it come to its fruition.” You don’t think those words are saying something emotional, but the music is so emotional. When I hear that song—and it’s one of the most gorgeous songs ever—it takes me there. The words are almost as important as the bass and drums. If you are Sting and your music is that good, it only adds to the mystique if listeners don’t get exactly what you’re saying.

I pretty much explain myself in my songs; I’m not very abstract. I like to be understood. As a songwriter, you make a decision early on about whether you want to be understood. The people who don’t want to be understood don’t really love what I do. They think it’s too fluorescent, transparent, or even boring. I’m not giving them anything to wonder about, just things to see. At the end of four and a half minutes, I want people to get it. I don’t want to give them more to wonder about.

A lot of young musicians think it would be great to become famous. Can you talk about fame from your vantage point?

Everything in your career is based on decisions. You have more control over the outcome of your life than you can imagine. If you are going to get into the arena where you will be famous, you’d better understand what that will mean. I’ve had to make some hard decisions at some points. I’d hear, “John, do you want to come to this premiere with this person, or do you want to go to this party where so-and-so will be? He really wants you to be there.” Some of those choices would mean that I’d appear in a newspaper or magazine, and then that would attract others to follow me with cameras. If I had done things differently, I’d probably have the paparazzi waiting around for me. At the studio where I’ve been recording, Jessica Simpson is working there, too. The paparazzi are outside waiting for her to come out. That’s the result of her decisions. My decisions have led me to the point that when I walk out in front of the paparazzi, I’m considered a waste of film.

Fame is interesting. It can come to life. You have to know yourself so well. There are nights when I want to get trashed on heartbreak, Hollywood, camera flashes, cars, the music and the romance, and pushing past the line. But those are tickets out. I’ve been able to somehow get all the things that people who want to be famous get without any of the things that make you think fame is not all it’s cracked up to be. I’ve passed up a lot of tempting things that would lead to things I don’t want. There is a lot of restraint involved. I am not in Us Weekly. I’d have to be going out with someone who is in there to be in there myself. But I get paid as much as the person who is on the cover.

What is your new record going to be like?

It will be defined by the people playing on it. Steve Jordan plays drums, Pino Palladino and Willie Weeks play bass, Roy Hargrove plays trumpet on it. It is in an r&b direction, but is hard to explain. Any label I put on it is going to make you think too far in one direction. It’s my voice and my sensibilities—which are growing—but it’s a little less wondrous. It’s a little more patient and a little less breathy in terms of the vocals. Would I be self-indulgent if I said it was cooler? There is a lot of guitar playing on it because the songs are written well enough so that more guitar makes sense. Eric Clapton is the greatest guitar player to me because he writes songs that lift the guitar playing to greater heights. He understands that if you want to be more than a guitar player’s guitar player, a people’s guitar player, you need to understand the lyric. I want to understand the lyric more.

At this point in your career, what are the dynamics like with your record company when you begin a new album?

I will show the album to them when it’s done, and they’ll put it out. I’m amazed to find that Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, and I are on the short list of artists at Columbia who can finish an album and walk into Don Ienner’s office and say, “Here you go.” There is a certain trust there. If you are on Columbia, you know you have to give them something that that they can bring to the world.

Does this put a lot of pressure on you?

No, it’s a lot of work and difficult, but it’s not high pressure. My second record was high pressure because they had the first record on their minds and I had to solidify my standing. I feel like I’ve done that. The two Grammys for “Daughters” sealed it up. I want to be a musician who can reach as many people as possible. At the same time, I hope to give them something interesting and a palette that is a little richer than what they are used to. I want to stretch them a little bit, and it doesn’t take much to do that.

It’s important to understand that when you’re on a record label, you are joining your bottom line to someone else’s. I want to do for my label and that means making a record that has hits on it. Sometimes your hits aren’t your best songs.

I think “Daughters” is a great song, but I never would have picked it to become such a big radio hit.

I didn’t think it would be either. The story behind that song becoming a hit is about trusting someone else’s view. If I hadn’t done that, it wouldn’t have been a single and people would have forgotten the Heavier Things album completely. But someone heard the song and said it would work. I said it wouldn’t. When I accepted the Grammy, I said I still didn’t think it was a good choice for a single. You’re not always right, so it’s important to assemble a team of people who are right more often than you are.

How would you like people to see your career 20 years from now?

I’d like them to see it as a lot of different train cars and a lot of incarnations. I don’t think I have a John Mayer sound. I have a difficult time when one of my records comes out on the radio. For the first four bars, you don’t know it’s me. That’s not so with the Rolling Stones. My first obligation is to flesh out the ideas in my brain. I don’t want my fingerprint to be a sonic fingerprint, but one based on a quality level. When people look back over the years, I’d like them to say that the only thread linking it all together was quality. Everybody should be going for that.